August 20, 2024

Speed is a well-documented risk factor in severe crashes involving bicyclists. The chance of a bicyclist fatality doubles at vehicle speeds of 30 miles per hour and continues to increase exponentially with higher speeds. The National Transportation Safety Board’s 2019 report on Bicyclist Safety on U.S. Roadways: Crash Risks and Countermeasures, which analyzed 173,000 bicycle crashes involving motor vehicles, found that while 65 percent of bicyclist crashes occurred at intersections, more than half of bicyclist fatalities occurred at midblock locations.

The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA)’s Bikeway Selection Guide summarizes what our profession has come to understand about the need for separated bicycling facilities. While shared lanes or bike boulevards (which mark space for bicyclists on a shared roadway and set car speed limits at bicycle-friendly numbers, respectively) can work under the right conditions on low-speed, low-volume roads, when roadways service more than 2,000 vehicles per day or have speeds exceeding 20 mph, bicyclists need a dedicated lane, preferably with a buffer. And when those number climb even higher—more than 30 mph and 6,000 vehicles per day—it is simply not safe or comfortable for bicyclists not to have a fully separated bicycling facility, defined as a lane intended exclusively for people on bikes and scooters that contains a horizontal buffer to separate users from car traffic, and a vertical element within the buffer space.

What about when posted speeds hit 35 mph or higher? While the fundamental recommendation (a separated bike lane) doesn’t change, the design considerations need to be commensurate with the vehicle speeds. What buffer distance will help bicyclists feel comfortable traveling next to high-speed vehicles? What vertical separation could withstand high-speed velocity?

Until now, agencies have been challenged by a lack of examples and guidance for how to safely provide bicycling facilities on higher-speed roads, since the majority of bicycle lanes in the U.S. have been built on roads in the 25–35 mph range, and most existing guidance does not provide design distinctions for higher speeds. As a result, there are very few applications of separated bike lanes on higher-speed roads, leading to either unsafe facilities or bicycling network gaps that, if filled safely, could connect bicyclists of varying abilities and confidence levels to key destinations, transit stations, and their communities as a whole.

With a goal to get more separated bicycling facilities on our roads in general, and on higher-speed roads specifically, FHWA released Separated Bike Lanes on Higher Speed Roadways: A Toolkit and Guide. This new guide documents best practices for the planning and design of bicycling facilities on roadways with a posted speed limit of 35 mph or higher.

This new guide documents best practices for the planning and design of bicycling facilities on roadways with a posted speed limit of 35 mph or higher.

Kittelson was honored to work with FHWA to lead the development of this guide, and we’re excited for its potential to pave the way for safer and more comfortable bicycling facilities on roads that have historically posed major safety challenges for people traveling on two wheels.

What’s In Separated Bike Lanes on Higher Speed Roadways

As any researcher will tell you, it’s ideal to have a large sample size from which to draw patterns and conclusions. Given there aren’t many separated bike lanes on higher-speed roads in the U.S. today, we didn’t have that luxury; so when researching for the guide, we opted for depth over breadth in our analysis of existing applications. With each installation, we learned the story and background, then interviewed the agencies that had designed and implemented them to understand what they learned. Every agency had insightful takeaways for us, from what materials they used to what design details they considered, and what outcomes they have seen as a result. We were also able to add to our sample size by pulling in a few international examples.

The guide organizes our findings across planning, designing and maintenance. Here’s a taste of the topics that are covered:

-

- Enacting supportive policies. Local policies can support separated bicycle lanes on higher-speed roads by requiring separation where bicycle lanes are present.

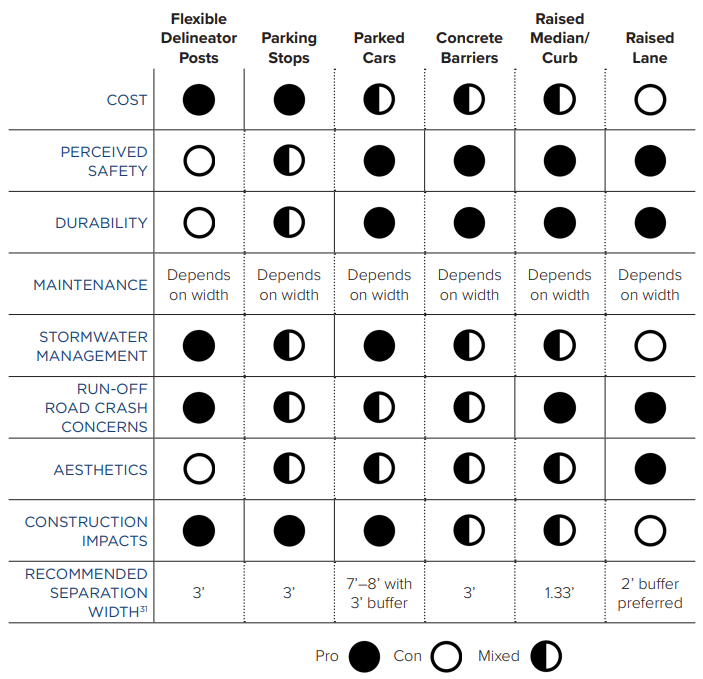

Table 2 in the guide shows the pros and cons of various separation materials.

- Horizontal and vertical separation. While vertical separation is essential, horizontal separation can be just as important because bicyclists will be more comfortable with offset from vehicles. This section describes the tradeoffs of different forms of separation types, including delineator posts, parked cars, concrete barriers, raised medians, and raised bike lanes. Separation types can also be used in combination to realize the full benefits of several treatments at a lower overall cost.

- Design guidance for intersections and driveways. Particularly on higher-speed roads, designers should maintain separation on the bike facility for as long as possible through the intersection. “Mixing zones,” where bikes and cars share the space preceding an intersection, are not recommended at higher speeds. Fully separate signal phases for bicycles and motor vehicles are preferred.

- Maintenance considerations. Maintenance takes careful planning and coordination to sustain safe operations on a separated bike lane. This section goes over considerations for stormwater, asset management, street sweeping, and seasonal maintenance.

The guide was built as a “toolkit”, recognizing a practitioner is more likely to grab it off the shelf when they want to jump to something specific rather than reading it cover to cover (unless that’s your idea of a relaxing Saturday morning). Each section contains information and guidance, examples, and key takeaways and is easy to navigate through a visual-heavy layout.

Separated Bike Lanes on Higher-Speed Roads in Action

Two cities we spoke to while developing the guide were Austin, Texas, and Pomona, California.

Slaughter Lane, in Austin, is marked at 45 mph with four to six lanes of vehicle traffic. Previously, the bike lane along this corridor was buffered only by paint. Since the beginning of 2019, Vision Zero data has reported six pedestrian or bicyclist-vehicle crashes (resulting in five serious injuries and one fatality). Beginning in November 2021, the City of Austin has been replacing the painted bike lane with a 5-6 inch raised curb.

One early lesson learned is the City received complaints from drivers who blew a tire from driving onto the corner of one of these curbs. In response, the City tapered the front end of the curb. This is a good example of an agency’s dedication to balancing dedicated modal needs, so that both drivers and bicyclists can safely travel along the road.

The first separated bicycle facility in Pomona is a two-way lane extending 1.5 miles down Valley Boulevard, also a 45 mph street, that connects neighborhoods to educational facilities, including Cal Poly Pomona. Bicyclists are separated from drivers through a mostly continuous raised curb combined with flexible delineator posts. As you can see, this design provides even more horizontal separation, which can improve comfort levels of people biking.

A separated bike lane in Pomona, California, protects bicyclists from drivers through a mostly continuous raised curb. Credit: Joe Linton/Streetsblog.

These examples are written up in the guide as case studies, along with several other features of U.S. cities that have pioneered separated bicycling facilities on higher-speed roads.

Shifting into High Gear with Separated Bike Lanes

“Even though there are still a limited number of examples to study, and we want to get that number higher, I was encouraged to find several real and robust applications of separated bike lanes on higher-speed roads in the U.S. today,” said Conor Semler, one of the guide’s authors. “When I think back to working on the NACTO Urban Design Guide in 2010, there were probably a similar number of separate bike lanes of any kind—and look where we are now!”

Conor says that 2010 guide, and others that have followed, have paved the way for many more separated bicycling facilities to be constructed across the country, and the goal of FHWA’s new guide is to accomplish the same on higher-speed roads. “We are hopeful this guide shows more agencies that this is possible. FHWA is calling on agencies to construct more of these facilities so that we can keep collecting information and refining best practices over time.”

Our industry is moving toward an understanding that separated facilities for bicyclists on any roadways with substantial speeds and volumes is not just a want; it’s a need. Now, agencies can refer to documented guidance so they can more confidently assess tradeoffs and make design decisions when they know bicyclists will be traveling alongside fast-moving traffic. Check out the published guide here, and reach out to us if you’d like to discuss further!