March 17, 2022

In an 1896 interview with famed journalist Nellie Bly, suffragist Susan B. Anthony said, “Let me tell you what I think of bicycling. I think it has done more to emancipate women than anything else in the world. I stand and rejoice every time I see a woman ride by on a wheel. It gives a woman a feeling of freedom and self-reliance. It makes her feel as if she were independent. The moment she takes her seat she knows she can’t get into harm unless she gets off her bicycle, and away she goes, the picture of free, untrammeled womanhood.”

To honor Women’s History Month, we are taking a closer, more complicated look at the history of women and the bicycle. The bicycling craze of the 1890s had a profound impact on the rights and roles of women in American society. But attributing the emancipation of women to a humble two-wheeled spoked machine gives an instrument of technology too much credit. The bicycle did not usher in a new era of women’s rights; instead, brave women used bicycles as a tool, claiming the machine and public space for themselves and one another. Even today, the bicycle becomes a vehicle of liberation for communities who are marginalized.

The bicycle did not usher in a new era of women's rights; instead, brave women used bicycles as a tool, claiming the machine and public space for themselves and one another.

Early Bicycles

Displayed by Comte de Sivrac in 1791 through the Parisian Palais Royal gardens, the first known bicycle was unsteerable and made of wood, but it proved popular with sporting men in Paris. Thirty years later, improvements in the form of a steerable front wheel and padded seat drove the popularity of this vélocipède higher. But while England briefly saw an explosion of velocipede riders, the fad quickly faded by the 1820s.

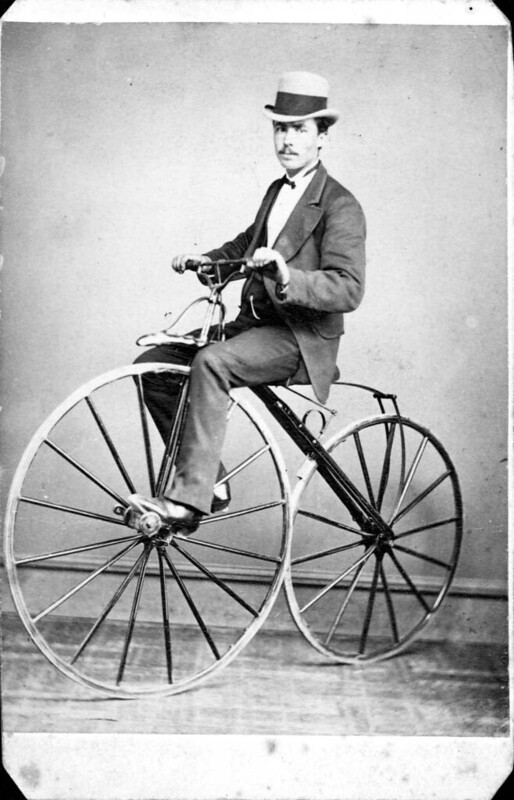

The addition of pedals to the front axle in 1863 brought the velocipede to the United States. Initially celebrated by young men at elite universities, the sport declined, suffering from heavy, cumbersome machines and increasing city ordinances preventing riding on pedestrian sidewalks. Moreover, mid-century velocipedes were challenging to ride-as one had to pedal and steer the same front wheel-and exceptionally rough due to a lack of padding and the rough state of most American roads.

The addition of pedals to the front axle in 1863 brought the velocipede to the United States. Initially celebrated by young men at elite universities, the sport declined, suffering from heavy, cumbersome machines and increasing city ordinances preventing riding on pedestrian sidewalks. Moreover, mid-century velocipedes were challenging to ride-as one had to pedal and steer the same front wheel-and exceptionally rough due to a lack of padding and the rough state of most American roads.

By the late 1870s and 1880s, the high-wheeled “Ordinary” took hold of American cyclists, nearly all of whom were men. Bicycle clubs provided the social network for such sportsmen. According to author and scholar Sarah Hallenbeck, “With high membership dues and stringent character requirements, organized rides and races, uniforms, and social events, club life helped strengthen and stabilize the network surrounding the Ordinary bicycle. However, the barriers to entry for club membership encouraged riders across the country to think of riding as a certain type of activity (masculine, modern), undertaken by certain members of society (respectable, professional class) within certain contexts (racetracks, club rides, tours).”

Ordinaries were light and fast but dangerous, as the rider sits just behind the bicycle’s center of gravity. Head-over-handlebars accidents were common. “Safety” bicycles-the evenly-sized wheeled machines we know today-emerged as a safer alternative in the 1890s. Pneumatic tires and brakes further improved riders’ experience and safety. Safety bicycles exploded in popularity. In 1889, there were an estimated 200,000 bicycles produced each year. Just ten years later, that number grew to more than 1,000,000. By 1899, bicycles were meeting much of the urban individual-transportation demand previously served by horses and carriages and public transportation.

Claiming Space

As high-wheel bicycling initially took root in the late-nineteenth century United States, the sport was largely for elite White men. When women tricyclists appeared on the scene, according to Hallenbeck, they destabilized a cycling world dominated by White men. Hallenbeck argues that difficult and dangerous high-wheel bicycling affirmed nineteenth-century masculinity. But by writing manuals and designing clothing and gear that would support and encourage women riders, women increasingly built community around the bike and in technological and social spaces dominated and controlled by men.

Women Repairing Bicycle, c. 1895. From Wikimedia Commons.

By promoting and engaging in physically strenuous bicycling, late nineteenth-century women also challenged prevailing medical ideas about the supposed natural frailty of their bodies. (It’s important to note, however, that nineteenth-century scientific racism attributed frailty and delicate constitutions largely to upper-class White women.)

The physical requirements of riding a bicycle-as well as the very real risk of getting skirts caught in the gears and wheels-provided women a reason to shed restrictive corsets and heavy skirts. As most cycling clothing was designed for men, innovative and intrepid women designed and patented their own cycling attire. Their wearable technology used pulley and button systems to quickly lift skirts out of the way of the gears and spokes. Other pioneering women designed bicycle umbrellas and locks, innovations that improved cycling for everyone.

After the industrial revolution brought thousands of working-class women into urban factories, the proper social and cultural role of women was increasingly brought into question. As the safety bicycle-itself a product of industrialization-grew in popularity, so too did anxieties about ‘the Woman Question.’ The notion of women riding bicycles in trousers triggered a moral panic, as proponents of gender norms feared unchaperoned bicycling was a slippery slope to sex work. As more women turned to trousers for safe and comfortable biking attire, their symbolic resistance to restrictive clothing helped legitimize trouser-wearing more generally.

Kittie Knox, 1985

A woman’s race, ethnicity, and income all intersect and impact her experiences and opportunities. As the mainstream women’s rights movement intentionally left behind women of color, the bicycle became a tool for women of color to challenge the intersectional forces of oppression. In 1894, passionate and talented cyclist Kittie Knox defiantly and jubilantly rode her bicycle at the League of American Wheelmen (LAW) annual meeting in Asbury Park, New Jersey. That year, the club had restricted membership to Whites only. Knox was of biracial heritage and had gained her membership card in LAW prior to the policy change. Her celebrity-largely from a costume contest she had won that same summer with her homemade knickerbocker suit-and unabashed tricks at the meeting sparked a heated debate about the league’s color line. Knox “used the bicycle to catapult her out of the crowded streets of Boston and toward a spectacular form of celebrity and resistance to the expectations of womanhood, whiteness, and labor”¦,”according to scholar Christine Bachman-Sanders For women and women of color, the simple joy of riding can become a radical act.

The radical potential of the bicycle has been harnessed by women worldwide. After the post-World War II automobile boom, the Netherlands became a haven for cars. But with more cars came more traffic conflict. Car crashes killed more than 400 children in 1971 alone. In protest, Dutch mothers organized Stop de Kindermoord, holding bicycle demonstrations, occupying crash hot spots, and organizing “special days during which streets were closed to allow children to play.”

The Bicycle as Resistance Today

Women continue to use bicycles as a form of public resistance and symbol of power. Bicycles have been an important form of protest and visibility for women of color. In Los Angeles and New York during the summer of 2020, women organized rides to protest the murder of George Floyd and other Black lives taken by police violence. Founded in 2013 by Monica Garrison, Black Girls Do Bike connects women and girls of color to a supportive, joyful cycling community. The more than 100 US chapters of Black Girls Do Bike organize group rides and skill-sharing opportunities “to share positive images of ladies and their bikes to affirm the truth that black girls do indeed bike” and to “demystify cycling and be a liaison to help usher new riders past barriers to entry and into the larger cycling community.”

Women continue to use bicycles as a form of public resistance and symbol of power.

Cycling groups also provide vital safe spaces for women to build community around shared experiences of sexuality, gender identity, and gender expression. Cyclista Zine creates an intersectional, radial, decolonial and inclusive feminist print space for underrepresented cycling communities. The collaborative zine deconstructs the systems of oppression that actively exclude Black, Indigenous, and cyclists of color as well as femme, transgender women, and women riders. Radical Adventure Riders (RAR) was founded in 2017 as an educational and supportive community for femme, transgender, women, and nonbinary riders as well as Black, Indigenous, and cyclists of color.

Urban Design for Equitable Cycling Today

Both technology and community shape public space. Transportation engineers and planners have an important role in improving life outcomes and eliminate disparities for women and everyone else who bikes. And there is much work to be done.

According to the 2013 report Women on a Roll: Benchmarking Women’s Bicycling in the United States-and Five Keys to Get more Women on Wheels, the League of American Bicyclists posed five Cs (listed below) that get more women biking. The 5 Cs can provide a useful schematic and starting point, but more intentional practices are needed to truly achieve the “free, untrammeled womanhood” touted by Susan B. Anthony but actively fought for by people like Kittie Knox and the BIPOC and queer bicycling collectives today.

The freedoms offered by the bicycle do not transcend the hierarchies and systems that oppress us all. Our work to encourage biking must address systemic racism, sexism, classism, and the intersecting oppressions that cause harm, undermine the quality and validity of our work, and prevent us from creating true and lasting impact. Alongside planning and design, our work requires incorporating “soft infrastructure” strategies that reduce crime, harassment, and assault, and eliminate systemic racism and police violence.

Comfort-In general, the Women on a Roll report found women are most comfortable biking on quiet streets or bike boulevards; on off-street paths; or on two-lane or four-lane streets with bike lanes. Designing comfortable facilities throughout a community will create more spaces and routes for women who bike.

- Ensure bicycle parking and locker facilities have good lighting and visibility so they feel safe for all users.

- When designing bike lanes or paths, consider how features like street trees can provide shade and wind breaks along exposed stretches.

Convenience-Because they often take on more household and childcare responsibilities, women, on average, take more than 100 additional trips a year than men, according to this study. When bicycle facilities do not account for different needs-carrying passengers (likely to be young and therefore more vulnerable road users) and items like groceries and home supplies-cycling becomes impractical.

- Support the different needs of all caregivers and household members by providing greater connectivity to community assets and neighborhoods.

Consumer Products-For most of history, bicycles and their products have been designed for men and White people. In 2013, nearly 90 percent of bike shops in the US were owned by men, according to the Women on a Roll report. For much of cycling history, saddles were designed for narrower pelvises. Without more anatomically diverse saddle options, a woman’s soft tissues-rather than their firm sit bones-bear the pressures of riding. Furthermore, the cultural expectations and beauty standards imposed on women mean that perspiration and suitable clothing often create barriers to biking.

- When advising agencies on public safety events, consider the helmet needs of folks with afro-textured hair, locks, or braids.

- Support women- and BIPOC-owned bike businesses.

Confidence-Women are more likely than men to report a lack of confidence in their skills as a barrier to cycling, according to the report.

- Consider targeted educational and confidence-building resources as part of multimodal network plans.

Community-Bicycling communities-like the kind cultivated by Black Girls Do Bike-use interpersonal relationships and safe spaces to build women’s confidence, skills, and sense of solidarity. Look for community groups tapped into local women cyclists’ needs when engaging the public on a project or concept.

- Make sure images in policy documents and community engagement materials are inclusive and diverse.

For more than a century, women have used the bicycle to claim the right to public space. As decision-makers, multimodal planners, and facility engineers, it’s up to us to make sure women can ride their bicycles into the future.

“To truly make transformational change for all people who bike,” writes Urban Planner and Mobility Justice Leader Tamika Butler, “we must go beyond a “Bike Month” or an occasional unity ride. We also must get beyond the narrative that only people who (too often self-righteously) make a lifestyle decision to bike are worthy of our targeted marketing campaigns, advocacy, and celebration. We must get past a strategy that assumes cisgender white maleness as the norm”¦ Once we can get past these things as a bicycle community, we can finally celebrate what bicycling should truly be about-the power to be free and move freely.”