June 15, 2022

We tend to take walks because of how they make us feel: a walk can be romantic, or it can help us lose weight, or clear our heads after a hectic day. But our walks can have a grander effect as well, ones which we may not see or feel but which improve the health of our planet. In fact, according to the EPA, keeping these intangible effects in mind when deciding whether to walk or drive even short distances could have the same impact as taking 400,000 cars off the road; no mean feat, given that 29% of the country’s greenhouse gas emissions (a major cause of climate change) come from transportation.

But it’s difficult to take a walk if your community isn’t walkable. If we want to act as responsible stewards of our planet, ones who leave behind sustainable community infrastructure that will serve our grandchildren and beyond, then we need to rethink not just how we as individuals get from point A to point B, but how our existing infrastructure influences our transportation decisions. Reworking our communities to emphasize active transportation methods, like walking, biking, and using public transit systems (access to which requires users to walk), can play a large role in reducing the toll transportation takes on our environment.

But if we know that embracing active transportation would go a long way in the fight against climate change, what’s the hold up? Why haven’t transportation systems across America implemented user-powered solutions? What are some of the obstacles standing in the way of active transportation?

The fragmentary nature of decision-making in planning has created real blockages for government departments as they endeavor to bring active transportation to their communities. Studying places that have successfully managed to implement active transportation infrastructure might give us some insight as to how other cities can vault over the hurdles standing in their way.

The Roadblocks to Friendlier Streets

Many of the problems hindering active transportation implementations in communities are baked into how communities were and continue to be formed in America. Transportation follows land use, meaning that a community’s transportation planning can only ever be as good as its land use decisions. And vice-versa; a place’s available transportation options inevitably shape the development of new neighborhoods. Unfortunately, land use and transportation decisions are frequently made without one another in mind, producing results that come with a high environmental cost. A 2021 post by the Urban Institute, a D.C.-based research nonprofit, argues that by delegating land use decision making to Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and transportation decision making to the Department of Transportation (DOT), the United States initiated a trend of dividing decisions that should really be made in tandem, effectively making “it more difficult to develop urban environments that are easy to live in without having to rely on a car.”

Even when putting aside this issue of land use, state bylaws can also stymy proposals for active transportation. Several states’ transportation departments have bylaws that restrict the department exclusively to working on implementations involving automobiles. These bylaws effectively deprioritize active transportation implementations, leaving them without the same access to state funding, staff, and ownership. Moreover, traffic impact studies can sometimes dance around assessing the effects of active transportation implementations even if state law requires them to do so.

Ultimately, the fragmentary nature of decision-making in planning has created real blockages for government departments as they endeavor to bring active transportation to their communities. Studying places that have successfully managed to implement active transportation infrastructure might give us some insight as to how other cities can vault over the hurdles standing in their way.

In the early 1960s only 10% of Copenhageners traveled by bicycle. By 2018, that number had increased to 49%. The shift occurred in part thanks to the Danish urban designer and architect Jan Gehl, who believes the trick to making our cities more "friendly, livable, and lively" is to employ a systemic approach to designing cities that provide "a good urban habitat for Homo sapiens," not for cars or skyscrapers.

Putting Action into Transportation

Though fragmentation can hamper action, we’re encouraged by the innovation of cities that have answered the call to develop more sustainable transportation systems. Here are just a few:

Copenhagen, Denmark: Copenhagen offers an exemplary illustration of what can happen when a city fundamentally changes its philosophy on transportation. By changing the city’s modal priority from the automobile to the bicycle, the city transformed into one of the world’s most active transportation-friendly cities in less than four decades. While in the early 1960s only 10% of Copenhageners traveled by bicycle, according to Copenhagen’s most recent bicycle account, published in 2019 for the year 2018, 49% of all commutes within Copenhagen were completed via cycling.

- The shift occurred in part thanks to the Danish urban designer and architect Jan Gehl, who makes the point, in an interview with the American Society of Landscape Architects, that cities haven’t historically been designed from the point-of-view of humans. The trick to making our cities more “friendly, livable, and lively,” then, is to employ a systemic approach to designing cities that provide “a good urban habitat for Homo sapiens,” not for cars or skyscrapers.

- While independent bikeways and super bikeways play roles in Copenhagen’s cycling infrastructure and connect it to surrounding suburbs, the hallmark of Copenhagen’s cycling infrastructure is the unidirectional, protected bicycle lane, which uses curbs to insulate the person cycling from both vehicle traffic and people walking on sidewalks. An article from the Heinrich Böll Foundation, an independent, German public policy think tank, notes that the security of these lanes played a vital role not only in increasing cyclist safety, but in making cycling more equitable, as women and children were less likely to cycle without them.

Portland, OR: Stateside, Kittelson’s largest office resides in a city with a developed cycling infrastructure. According to the Smart Growth America 2015 report Safer Streets, Stronger Economies, since prioritizing active transportation in the mid-1990s, Portland has constructed 300 miles of bike lanes, boulevards, and walking paths. Rather than impede people who drive, the focus of the initiative was to empower people seeking to rely on user-powered modes of transportation; the report notes that this cycling network accommodated a 12% increase in cycling while vehicle rates remained constant.

New York City, NY: With the New York City Streets Plan, America’s largest city is also mounting an effort to retool its transportation system toward sustainable modalities. Originally passed in 2019, the Streets Plan directed $1.7 billion toward the Copenhagenization of New York City streets, building 250 miles of bicycle lanes and 150 miles of bus lanes over five years as part of an effort to “break the car culture.” More recently, in response to Mayor Eric Adams’ proposed budget cuts, the City Council renewed calls for sustainable transportation infrastructure, this time to the tune of $3.1 billion.

Most comprehensive active transportation initiatives formalize three broad goals for their implementations: improve user safety; increase user modality options beyond the car, lowering the city's carbon footprint; and increase equity by distributing these innovations citywide.

The Lessons of Copenhagenized Cities

Structural problems require structural solutions. What can we learn from these sample cities? What needs to happen for a city to build its systems around active transportation?

The community, starting with leadership, must embrace the advantages of shifting existing transportation paradigms, and commit to active transportation: Changing modal priority will level the playing field for people who walk or bike. Centering the automobile in transportation systems doesn’t just mean favoring an environmentally unsustainable modality; rather, privileging a car-centric modality often actively impedes the efficiency of people who walk or bicycle, meaning individuals may be disinclined to engage in active transportation. In order to ensure that all people driving spend less than two minutes at an intersection, for instance, you have to be willing for those people walking to wait longer at intersections.

However, this reprioritization is only possible if there’s a political will for it at the helm of any department of transportation. For this political will to translate into action, it has to come from the top down: if the city government doesn’t value active transportation, then new active transportation measures will face a steep uphill battle toward implementation, and existing active transportation infrastructure can even be stripped away.

New York City’s Streets Plan illustrates the highs and lows that come from having to rely on leadership. The legislation for the Streets Plan was “championed by Speaker Corey Johnson, passed by the City Council, and signed into law by Mayor Bill de Blasio”; once law, the legislation required NYC DOT to create a framework to “reduce [New York City’s] dependence on large, polluting, diesel trucks by shifting freight to waterways, our rail system, and other smaller, greener alternatives.” However, and despite pledging on the campaign trail to fund the project, Mayor Eric Adams has yet to dedicate funding to the implementations.

Importantly, while leadership for departments of transportation are appointed at all levels of government, the presidents, governors, and mayors who appoint them are elected. So although the political will to implement active transportation initiatives typically comes from the top, exercising the franchise to place in office individuals committed to sustainable transportation means this determination can find its way into the hands of the average citizen. According to the earlier report from the Heinrich Böll Foundation, the City of Copenhagen was first moved to incorporate cycling into their transportation planning when Copenhageners agitated for it outside City Hall.

If the city government doesn't value active transportation, then new active transportation measures will face a steep uphill battle toward implementation, and existing active transportation infrastructure can even be stripped away.

Once a city has shifted modal priority, developing metrics of success will be crucial for guiding active transportation implementation. Formalizing these metrics gives cities tools with which to measure both their progress implementing their modal shift as well as the positive ramifications of the treatments. Most comprehensive active transportation initiatives formalize three broad goals for their implementations:

- improve user safety;

- increase user modality options beyond the car, lowering the city’s carbon footprint;

- and increase equity by distributing these innovations citywide.

Portland’s bicycle network has made progress on all of these metrics. According to the same Safer Streets, Stronger Economies report, the network facilitated new modal access citywide, with bicycle commuting increasing 400% from 1990 to 2008. In the same timeframe, “bicycle fatalities steadily declined and for five years over that time period, the city reported no bicycle fatalities. That happened again in 2010 and 2013.”

Communities may also use financial metrics to measure the success of their active transportation implementations. Active transportation implementations are typically less expensive than vehicle-based implementations and can spur secondary economic growth in cities. Portland’s entire bicycle network cost the city $60 million dollars; for the same cost, Portland could have built “just one mile of a four-lane urban freeway.” Edgewater Drive, a neighborhood in Orlando, Fla., rejuvenated its downtown commercial strip by reworking its streets so people biking, walking, and driving could coexist more harmoniously. Injury rates fell, cycling numbers increased, and 77 new businesses opened across seven years.

Communities may also use financial metrics to measure the success of their active transportation implementations. Active transportation implementations are typically less expensive than vehicle-based implementations and can spur secondary economic growth in cities. [Infographic by Jessica Keller]

Once a city implements active transportation-friendly infrastructure, it can encourage user adoption by changing the perspective on individual burden. In many cases, individual citizens do not need to reinvent their every commute to make their transportation habits (and their transit systems) more sustainable.

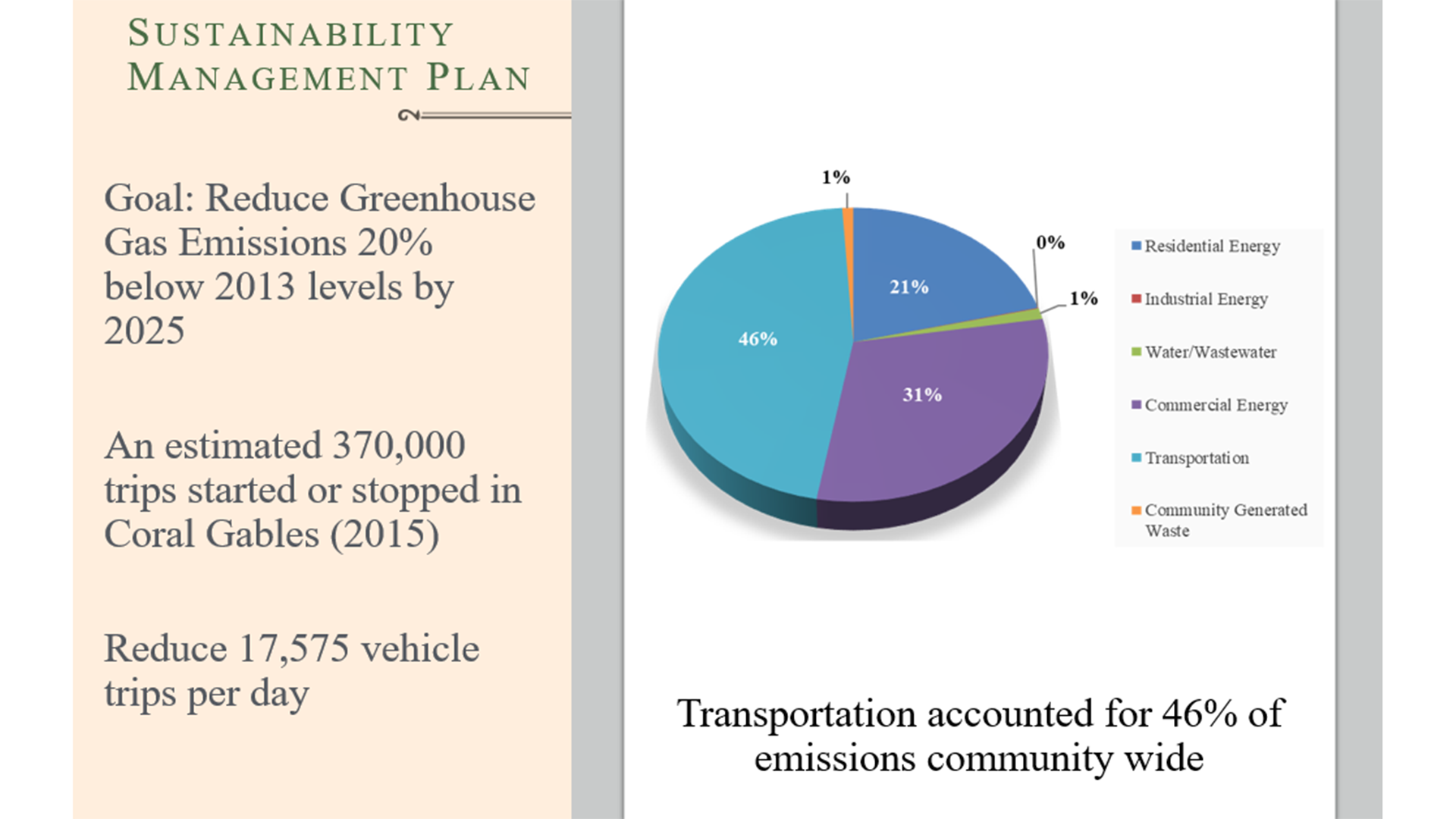

Even in communities especially vulnerable to the effects of climate change, like coastal cities, the individual buy in for transformative transportation can be low: for Coral Gables, Fla, to hit its emissions target of a 20% reduction by 2025, we found the city only needs to trim away 17,575 vehicle trips per day. With a 2020 adult population of approximately 39,448, if Coral Gables adult residents replaced one of their daily vehicle trips with a user-powered modality, they would nearly double the reduction necessary to meet the city’s emissions target. Leading individuals to embrace active transportation modalities starts by encouraging them to make modest lifestyle adjustments.

Continue the Conversation

At Kittelson, we tackle complex transportation issues facing planners and engineers collaboratively, and with optimism, initiative, and action. We’re committed to helping our clients examine the intersections of transportation, land use, sustainability politics, environmentalism, and planning, to make sure our communities can serve their citizens now and in the years to come. Feel free to reach out to discuss any of these ideas further!