September 14, 2022

Part II: 1980-Today

We left our journey through transportation music history in the 1970s, with a country squeezed by the oil embargo at home and seeking new frontiers in outer space. (If you missed part one of this series, you can read it here!) In this second and final installment, we’ll listen in as the intertwined histories of popular music and transportation history explored new mediums, claimed public space, and revived old modes.

1980s-Music Videos

The 1980s was a time of conservative social and economic policy, a continuation of the Cold War, and a generation of young, educated professionals with money to spend. However, not everyone felt part of the new social order. Cue MTV, a cable television channel that (originally) exclusively played music videos. MTV first aired on August 1, 1981, with the Buggles’ Video Killed the Radio Star. The extremely popular medium would make the 1980s the heyday of the format, with music videos propelling the careers of artists like Michael Jackson and Madonna.

Classic, luxury, and muscle cars were a major feature of rock and roll videos during this period, even when a song wasn’t about a car or driving at all. These vehicles gave bands cultural cache, communicating their cool factor to audiences everywhere.

Even though the song includes no references to a vehicle, a Cadillac Fleetwood Eldorado convertible is central to the music video for Judas Priest’s heavy metal Breaking the Law (1980). The video opens with lead vocalist Robert Halford singing from the back of the convertible, on his way to rob a bank with the power of the band’s guitars. After liberating their golden record award, the band rides away, shredding from the back seats of the Cadillac as it speeds down the highway.

Sammy Hagar’s I Can’t Drive 55 (1984) music video pulled over for speeding in a racecar, appear in court in their race suits, rocking from the jail cell where they eventually escape and ride off into the sunset”¦ driving well above 55.

One foot on the brake and one on the gas, hey

Well, there’s too much traffic, I can’t pass, no

So I tried my best illegal move

A big black and white come and crushed my groove again

Go on and write me up for 125

Post my face, wanted dead or alive

Take my license, all that jive

I can’t drive 55

Oh no, uh

-Sammy Hagar, I Can’t Drive 55, 1984.

The legendary Whitesnake music video for Here I go Again (1987) alternates between shots of the band playing on a stage and model Tawny Kitaen dancing on the hood of two Jaguar XJs. Other notable music videos with rad rides include ZZ Top’s Gimme All Your Lovin and B-52’s Love Shack.

If you see a faded sign at the side of the road that says

Fifteen miles to the, love shack, love shack yeah

I’m headin’ down the Atlanta highway

Lookin’ for the love getaway

Headed for the love getaway, love getaway

I got me a car, it’s as big as a whale

And we’re headin’ on down to the love shack

I got me a Chrysler, it seats about twenty

So hurry up and bring your jukebox money

-The B-52’s, Love Shack, 1989.

1990s-Urban Car Culture

For many in the music industry, the late 1980s and early 1990s were the golden age of rap and hip hop, a time when originality and innovation were everywhere. As a musical genre and cultural movement, hip hop was a way for Black artists who had long been marginalized politically, socially, and culturally to claim a public voice and public space. Car culture and hip hop used art for public expression and tied that expression to a particular place. Black communities in New York, Miami, Los Angeles, and Houston all developed distinct car cultures.

Southside Black communities in Houston, Texas, developed a car culture known as Slab and a rapping style known as Screw in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Slab and screw emerged from communities decimated by social and economic changes in the 1980s. With few opportunities for upward mobility and more than 20 percent of Black Houstonians living in poverty, some Southside residents turned to underground economies. Car culture became a way to mark success in this illicit trade.

Slabs-named for the pavement of Houston or as an acronym for “slow, loud, and bangin”-are old American luxury sedans, like Cadillacs, Lincolns, and Oldsmobiles, outfitted to be seen and heard with loud ‘candy’ paint jobs, booming bass sound systems, and special 1980s elbow rims called swangas. Slab builders were skilled craftsmen, sourcing cars in disrepair and transforming them into custom works of art. Slab owners would meet up for swangin, in which drivers operate as a single-file unit, slowly weaving from lane to lane. Swangin actively reinforced bonds between individuals and their community, according to folklorist, ethnomusicologist, and Houston-native Langston Wilkins.

Slab merged with hip hop in the mid-1990s with artists involved in the music and street industries. “Chopped and screwed” was a type of hip hop created by Houston artist DJ Screw and popularized by the Screwed Up Click (S.U.C.) collective. Screwing slowed down a song’s tempo; chopping skipped beats, scratched records, and stop-timing. Screw music was perfect for slab, the slow music designed for swangin and the heavy bass accentuated Slab sound systems. Markers of rappers’ success, Slabs also became a symbol of tension, as violence broke out between north and southside communities.

The legacy of slab and screw runs strong in Houston today. The art forms remain a point of community pride and affirmation, with annual slab parades and meet-ups.

@houstonslabpage Still tippin baby 🤟ðŸ½ðŸ”¥ #houston #northside #fypã‚· #cartalk #slabtalk #vogues #covid19 #besomeone ♬ original sound – Houstonslabpage

2000s & Today-Rideshare and Micromobility

Music from the past 20 years has started to reflect hallmarks of twenty-first century transportation: rideshare services like Uber and Lyft and micromobility services. Although they feel quite new today, these modes are actually on their second tour in American culture.

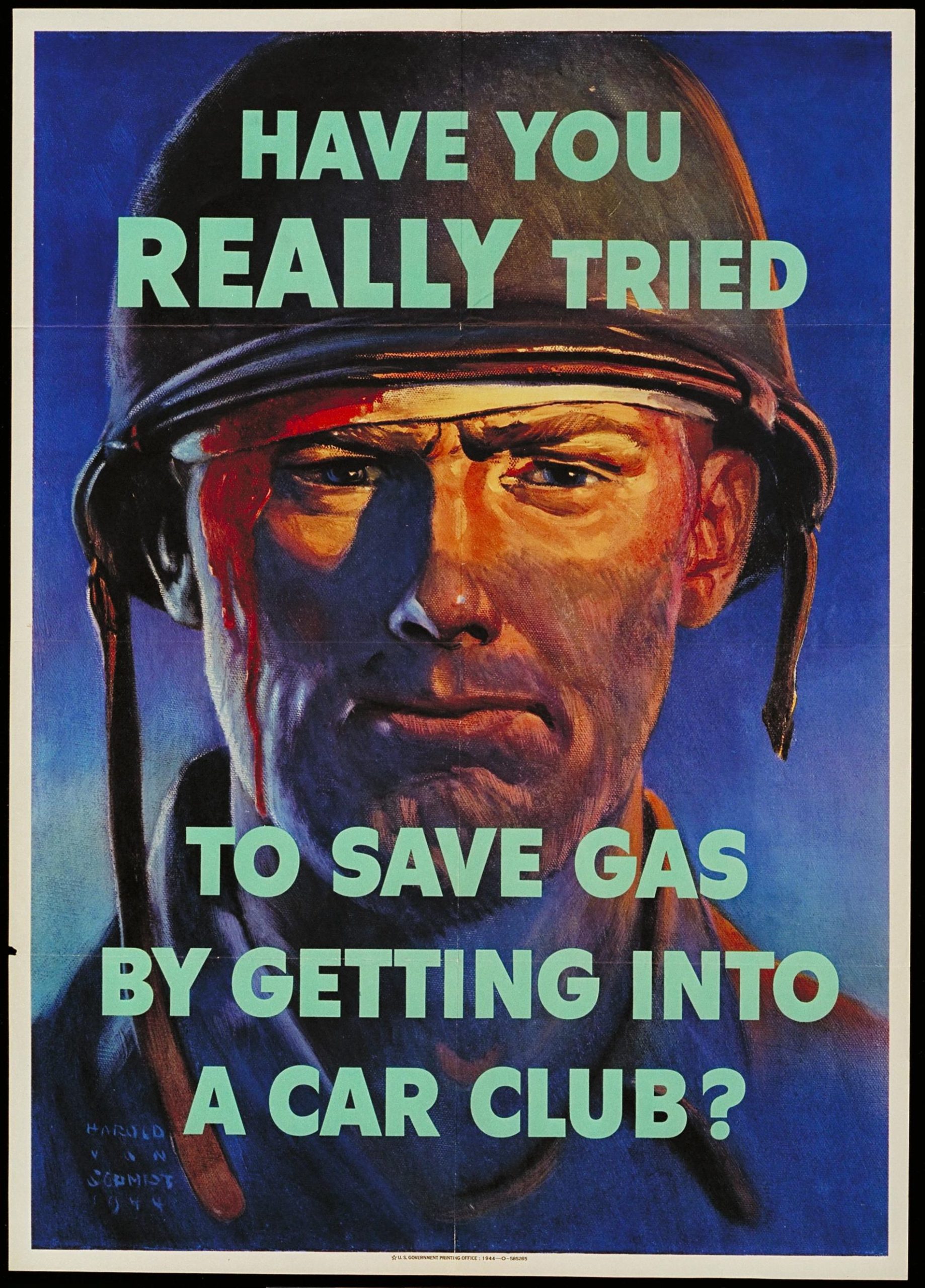

Despite its rapid proliferation with the internet and mobile apps after the late 90s, ridesharing is not new. Shortages and wartime recessions during both world wars sparked carpooling and rideshare services in cities across the US, according to a history of rideshare from MIT. During World War I, people who owned personal vehicles offered an alternative to streetcars, picking up passengers for the five-cent streetcar fare called ‘a jitney’. During World War II, the US government encouraged ridesharing as an act of patriotism.

Photo courtesy of the Government & Geographic Information Collection, Northwestern University Libraries. "Have you really tried to save gas by getting into a car club?", World War II Poster Collection, https://dc.library.northwestern.edu/items/73945885-fa06-490c-b414-a1b2217a451a

Nearly a century since rideshare’s wartime roots, companies like Uber and Lyft rode the expansion of internet services and smartphone apps through the 2010s, proliferating their services throughout US cities. Careful listening reveals this mode’s growing influence on popular culture. Uber shoutouts appear in songs by hip hop and rap artists Childish Gambino, Chance the Rapper, Wiz Khalifa, Rick Ross, Young Thug, Lil Wayne, and Wale.

Even newer than rideshare, electric micromobility first debuted in Santa Monica, California in 2017. The autoped, one of the e-scooters’ earliest motorized ancestors, was developed by a New York company in 1915. Autopeds look strikingly similar to the Birds and Limes of our streets today. In addition to being delightful to ride, e-scooters can fill critical first and last-mile gaps in transportation networks. In their 2020 track, Electric Scooter, UK rap duo Frankie Stew and Harvey Gunn recognize the e-scooter’s potential to replace a personal vehicle for city-dwellers.

Even newer than rideshare, electric micromobility first debuted in Santa Monica, California in 2017. The autoped, one of the e-scooters’ earliest motorized ancestors, was developed by a New York company in 1915. Autopeds look strikingly similar to the Birds and Limes of our streets today. In addition to being delightful to ride, e-scooters can fill critical first and last-mile gaps in transportation networks. In their 2020 track, Electric Scooter, UK rap duo Frankie Stew and Harvey Gunn recognize the e-scooter’s potential to replace a personal vehicle for city-dwellers.

Everybody’s on my case bout driving test I’ve got no car.

I wanna get one of them electric scooters that goes uphill fast.

-Frankie Stew & Harvie Gunn, Electric Scooter, 2020

Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Autoped_scooters#/media/File:Lady_Florence_Norman.jpg.

The Future of Transportation Music

The freedom to move through public space is a fundamental component of our society and culture. Paying attention to how deep the roots grow helps underscore the importance of our planning and engineering work. In 20 years, what will artists celebrate or lament? Will the cowboy lose his automated 4×4 truck? Will Avril sing about E-Scooter Boi?