August 10, 2022

Part I: 1920-1970

Transportation and music go hand in hand: A cyclist pedaling to the beat of attached speakers. Rows of bus riders with earbuds bobbing quietly to unknown genres. Teenagers pulling up to a red light, car visibly vibrating from heavy bass. The pedestrian in headphones grooving out while waiting for the walk signal. Many of us have carefully cultivated playlists for bus trips, long bike rides, and walks to work. Some of us take our chances with the radio, flipping channels in the car until we find something suitable.

But what does it mean when the music we listen to is about transportation? To answer this question, we loosely tracked transportation themes in popular music in the United States from about 1920 to the present day.

For a sampling of our findings, check out our Spotify Playlist:

By nature, popular music has a reflexive relationship with larger social and cultural forces. This means that while it reflects these forces, it also influences them. Taking a closer look at popular music and transportation sheds light on the degree to which transportation is integrated into the fabric of communities. We do not intend this musical journey to be exhaustive or comprehensive, and our periods overlap. (History stubbornly resists neat decade rules). Rather, we intend this story to illustrate how the tightly bound relationships between transportation, infrastructure, history, and culture have changed over time.

1920s & 1930s-Hobos and Railroads

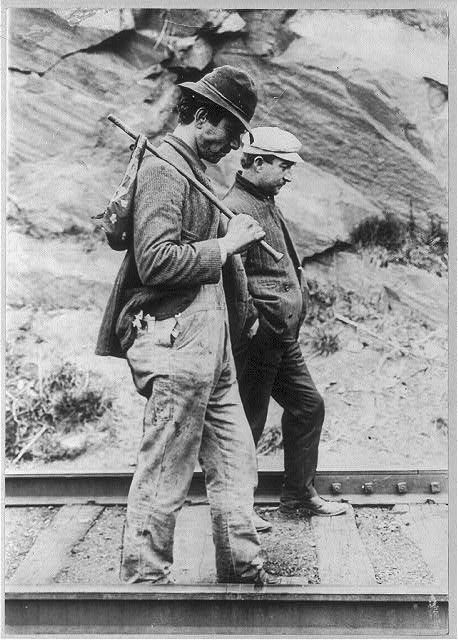

When the American Civil War ended in 1865, many displaced veterans turned to a life of hopping train cars and riding a rapidly expanding rail system. Between 1871 and 1900, the nation’s railroad lines grew by more than 170,000 miles. When the US economy crashed in October 1929, the number of people living on the road or rail grew exponentially. Pushed out of a disintegrating economy and highly visible in communities across the US, a distinct “hobo” subculture emerged as this transient population grew alongside the rail network.

Out of this subculture emerged both folklore and folk music tied to the rail-riding experience. It is here we get songs like Big Rock Candy Mountain, originally recorded in 1928 by Harry McClintock, aka “Haywire Mac.” The popularized (and considerably sanitized) version of Big Rock Candy Mountain, which hit #1 on the Billboard country music chart in 1939, is the story of a hobo telling his fellow riders about their version of paradise. Here, the vulnerabilities of life on the rails-potential arrest by “railroad bulls,” financial insecurity, and scarcity of resources vanish-replaced by polite railroad security officers, plentiful handouts, and never-ending food and drink:

In the Big Rock Candy Mountains

There’s a land that’s fair and bright

Where the handouts grow on bushes

And you sleep out every night

Where the boxcars all are empty

And the sun shines every day

“¦

In the Big Rock Candy Mountains

All the cops have wooden legs

And the bulldogs all have rubber teeth

And the hens lay soft-boiled eggs

The farmers’ trees are full of fruit

And the barns are full of hay

“¦

In the Big Rock Candy Mountains

You never change your socks

And the little streams of alcohol

Come a-trickling down the rocks

The brakemen have to tip their hats

And the railroad bulls are blind’

-Harry “Haywire Mac” McClintock, Big Rock Candy Mountain (1928)

Image: Photograph of two hobos walking along the railroad tracks. Photographer Unknown. Photo Credit: https://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/cph.3a50795/.

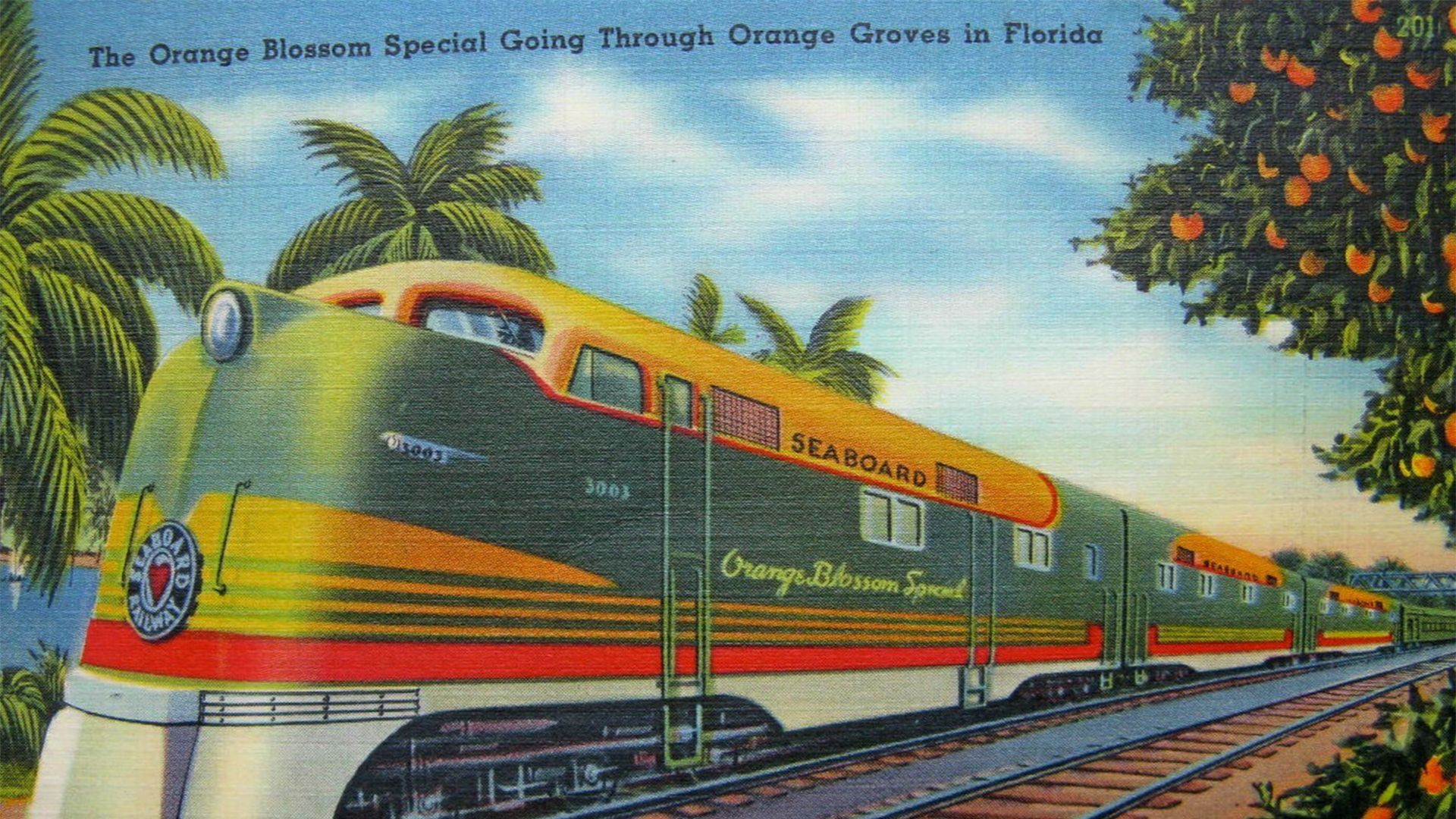

In the 1930s, we also find music that references important engineering advancements using instrumental sound. The Orange Blossom Special was a passenger train that served Miami and New York City during the winter months. Ervin T. Rouse’s Orange Blossom Special (1938) uses a fiddle with increasing tempo to mimic the sounds of a train leaving the station and picking up speed. (When Johnny Cash recorded his version of Orange Blossom Special in 1965, he used a harmonica and his own voice for the train horn.) Rouse’s emphasis on acceleration is noteworthy because of the train’s key feature: two, 2000-horsepower locomotives that applied power at 24-wheel points and enabled the train to take off, reach a high speed, and stop more quickly, according to the Tampa Daily Times (December 15, 1939).

In the 1930s, we also find music that references important engineering advancements using instrumental sound. The Orange Blossom Special was a passenger train that served Miami and New York City during the winter months. Ervin T. Rouse’s Orange Blossom Special (1938) uses a fiddle with increasing tempo to mimic the sounds of a train leaving the station and picking up speed. (When Johnny Cash recorded his version of Orange Blossom Special in 1965, he used a harmonica and his own voice for the train horn.) Rouse’s emphasis on acceleration is noteworthy because of the train’s key feature: two, 2000-horsepower locomotives that applied power at 24-wheel points and enabled the train to take off, reach a high speed, and stop more quickly, according to the Tampa Daily Times (December 15, 1939).

Image: This Postcard (postmarked 1939) depicts the Seaboard Air Line Railroad’s Orange Blossom Special. Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Seaboard_Airline_Railroad_Orange_Blossom_Special_1939.JPG

Well, I’m going down to Florida

And get some sand in my shoes

Or maybe Californy

And get some sand in my shoes

I’ll ride that Orange Blossom Special

And lose these New York blues

“¦

Hey talk about a-ramblin’

She’s the fastest train on the line

Talk about a-travellin’

She’s the fastest train on the line

It’s that Orange Blossom Special

Rollin’ down the seaboard line

-Ervin T. Rouse, Orange Blossom Special (1939)

Through the twenties and thirties, the lyrics and melodies of music about railroads captured the potential of transportation to influence society and technology. Both songs have undergone several revivals in subsequent decades (including in the film O Brother, Where Art Thou?), and their popularization attests to rail’s deeply-rooted connection to American culture.

1940s-Trolleys & Trains

Trains-and trolleys-retained their place of prominence in popular music through the 1940s. In the mid-1940s, people in the United States were mired in the collective trauma and social upheaval of World War II. Movies provided an escape from wartime horrors, and many production companies sought lighthearted films about simpler times. The Trolley Song in MGM’s Meet Me in St. Louis, starring Judy Garland, uses falling in love on an early nineteenth-century street trolley just before the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair. This nostalgic trolley ride betrays a yearning for an easier, more peaceful period of global relationships.

With my high starched-collar and my high-topped shoes

And my hair piled high upon my head

I went to lose a jolly hour on the trolley

And lost my heart instead

With his light brown derby and his bright green tie

He was quite the handsomest of men

I started to yen so I counted to ten

Then I counted to ten again

Clang, clang, clang went the trolley

Ding, ding, ding went the bell

Zing, zing, zing went my heart strings

From the moment I saw him I fell

-Judy Garland and the cast of Meet Me in St. Louis, The Trolley Song (1944)

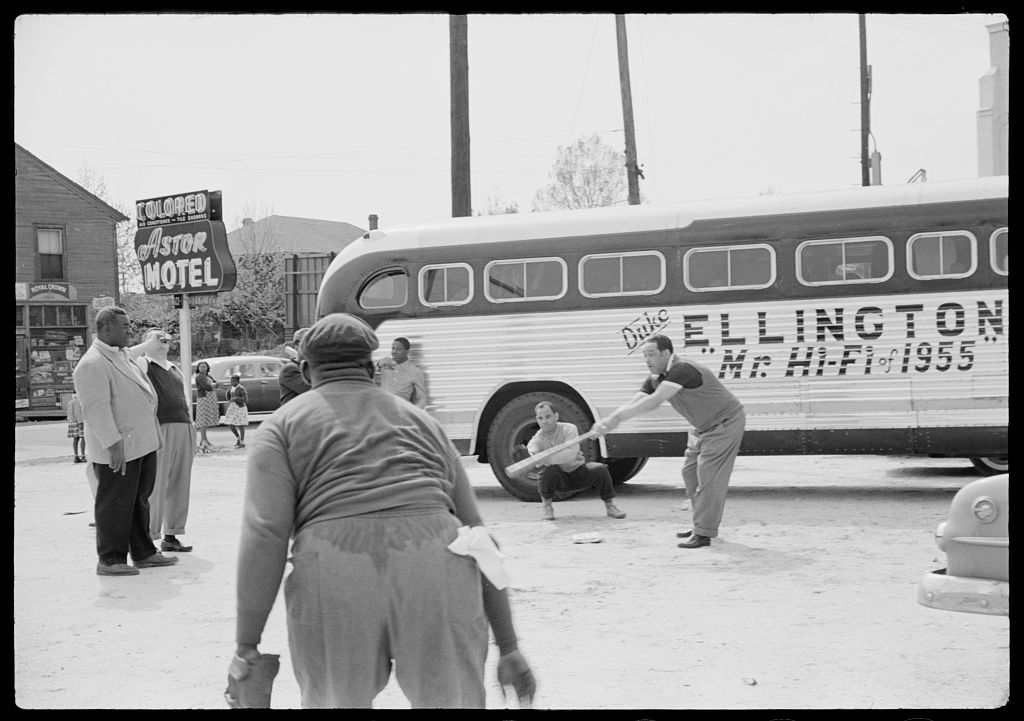

During this same period, Black communities were experiencing considerable change as part of the Great Migration, where more than six million Black people fled racial violence in the South and sought economic and educational opportunities in the North, Midwest, and West from about 1910 to 1970. For new and developing Black communities, trains provided vital connections between work and home. Duke Ellington’s Take the ‘A’ Train (1944) references a new transit line that connected Harlem, Manhattan’s central Black community to the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood, which quickly became Brooklyn’s central Black residential neighborhood.

You must take the A Train

To go to Sugar Hill way up in Harlem

If you miss the A Train

You’ll find you’ve missed the quickest way to Harlem

Hurry, get on, now, it’s coming

Listen to those rails a-thrumming (All Aboard!)

Get on the A Train

Soon you will be on Sugar Hill in Harlem

-Duke Ellington, Take the ‘A’ Train (1944)

The Trolley Song and Take the ‘A’ Train showcase two different perceptions of the same mode of transportation. For some, transit systems offered escapism and romantic wistfulness. For others, transit represented a tool for community building and beacon of opportunity. Perceptions of transit, however, changed dramatically after the popularization of the automobile.

1950s & 1960s-Rise of the Driver

In the 1950s and 1960s, lingering postwar production, high levels of employment, advertising, and federal programs worked together to create an economy of mass consumption. As Lizabeth Cohen argues in A Consumer’s Republic: The Politics of Mass Consumption in Postwar America (2008), consumption became the key to being a good citizen. Personal vehicles were a hallmark of purchasing power and a symbol of the “American Dream.”

In the 1950s and 1960s, lingering postwar production, high levels of employment, advertising, and federal programs worked together to create an economy of mass consumption. As Lizabeth Cohen argues in A Consumer’s Republic: The Politics of Mass Consumption in Postwar America (2008), consumption became the key to being a good citizen. Personal vehicles were a hallmark of purchasing power and a symbol of the “American Dream.”

Music of the period aligned with these currents, turning away from community transportation experiences, and celebrating the freedom and power of owning a personal car or motorcycle. The Beach Boys’ I Get Around (1964) finds the driver lamenting traveling the same roads and wanting to use his fast car to find new and exciting places.

Image: During the postwar period, owning a car and home in the suburbs became the symbol of consumer success. Image source: Leffler, Warren K, photographer. Woman and man, standing next to a car, looking at a house under construction in Arlington, Virginia. Arlington Virginia, 1966. [3 August] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2014647929/.

Round round get around, I get around

Get around round round I get around

From town to town

I’m a real cool head

I’m making real good bread

…

I’m gettin’ bugged driving up and down the same old strip

I gotta find a new place where the kids are hip

My buddies and me are getting real well known

Yeah, the bad guys know us and they leave us alone

…

We always take my car ’cause it’s never been beat

And we’ve never missed yet with the girls we meet

None of the guys go steady ’cause it wouldn’t be right

To leave their best girl home now on Saturday night

-The Beach Boys, I Get Around (1964)

Other songs-like Chuck Berry’s No Particular Place to Go (1964)-winked at the new, unsupervised freedom that personal vehicles offered young couples in the sixties. Steppenwolf’s early heavy metal hit Born to Be Wild, first released in 1967 and popularized a few years later (1969) in the counterculture road film Easy Rider became-and remains-an anthem for biker culture.

Get your motor runnin’

Head out on the highway

Looking for adventure

In whatever comes our way

-Steppenwolf, Born to Be Wild (1967)

The open road also offered another sense of freedom. According to historian Gretchen Sorin in Driving While Black: African American Travel and the Road to Civil Rights (2020), because of various housing policies and financial practices, owning an automobile became an important way people in Black communities exercised purchasing power and growing cultural capital. Personal vehicles were critical for cross-country travel, especially through “sundown towns,” municipalities that used local laws and policing to restrict Black travelers between dusk and dawn. Big, heavy vehicles meant Black travelers could pack the pillows, blankets, meals, and cans of gas they may need to avoid hostile motels and fueling stations. Chuck Berry’s rocking No Money Down (1955) celebrates postwar purchasing power and, when read closely, may allude to the very practices Sorin describes.

Well Mister I want a yellow convertible four door De Ville

With a Continental spare and a wire chrome wheel

I want power steering and power brakes

I want a powerful motor with a jet off-take

I want air condition, I want automatic heat

And I want a full Murphy bed in my back seat

I want short-wave radio, I want TV and a phone

You know I got to talk to my baby when I’m riding alone

Yes I’m going to get that car

And I’m going to head on down the road

Yeah, then I won’t have to worry

About that broken down, ragged Ford

-Chuck Berry, No Money Down (1955)

Finally, 1960s popular music about transportation offers us a glimpse at the growing frustrations facing drivers as congestion became more prevalent across the US. In the 1968 hit Crosstown Traffic by the Jimi Hendrix Experience, thinly veiled innuendo compares leaving last night’s lover with sitting in increasing urban congestion.

Finally, 1960s popular music about transportation offers us a glimpse at the growing frustrations facing drivers as congestion became more prevalent across the US. In the 1968 hit Crosstown Traffic by the Jimi Hendrix Experience, thinly veiled innuendo compares leaving last night’s lover with sitting in increasing urban congestion.

Image: In this 1955 photograph, legendary jazz musician Duke Ellington and his band members play baseball in the parking lot of their segregated motel. Image source: Brooks, Charlotte, photographer. Duke Ellington and band members playing baseball in front of their segregated motel “Astor Motel” while touring in Florida. Florida, 1955. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2009632168/.

I’m not the only soul who’s accused of hit and run

Tire tracks all across your back

I can, I can see you had your fun

But, darling can’t you see my signals turn from green to red

And with you, I can see a traffic jam straight up ahead

“¦

You’re just like crosstown traffic

So hard to get through to you

Crosstown traffic

I don’t need to run over you

Crosstown traffic

All you do is slow me down

And I’m tryin’ to get on the other side of town

-The Jimi Hendrix Experience, Crosstown Traffic (1968)

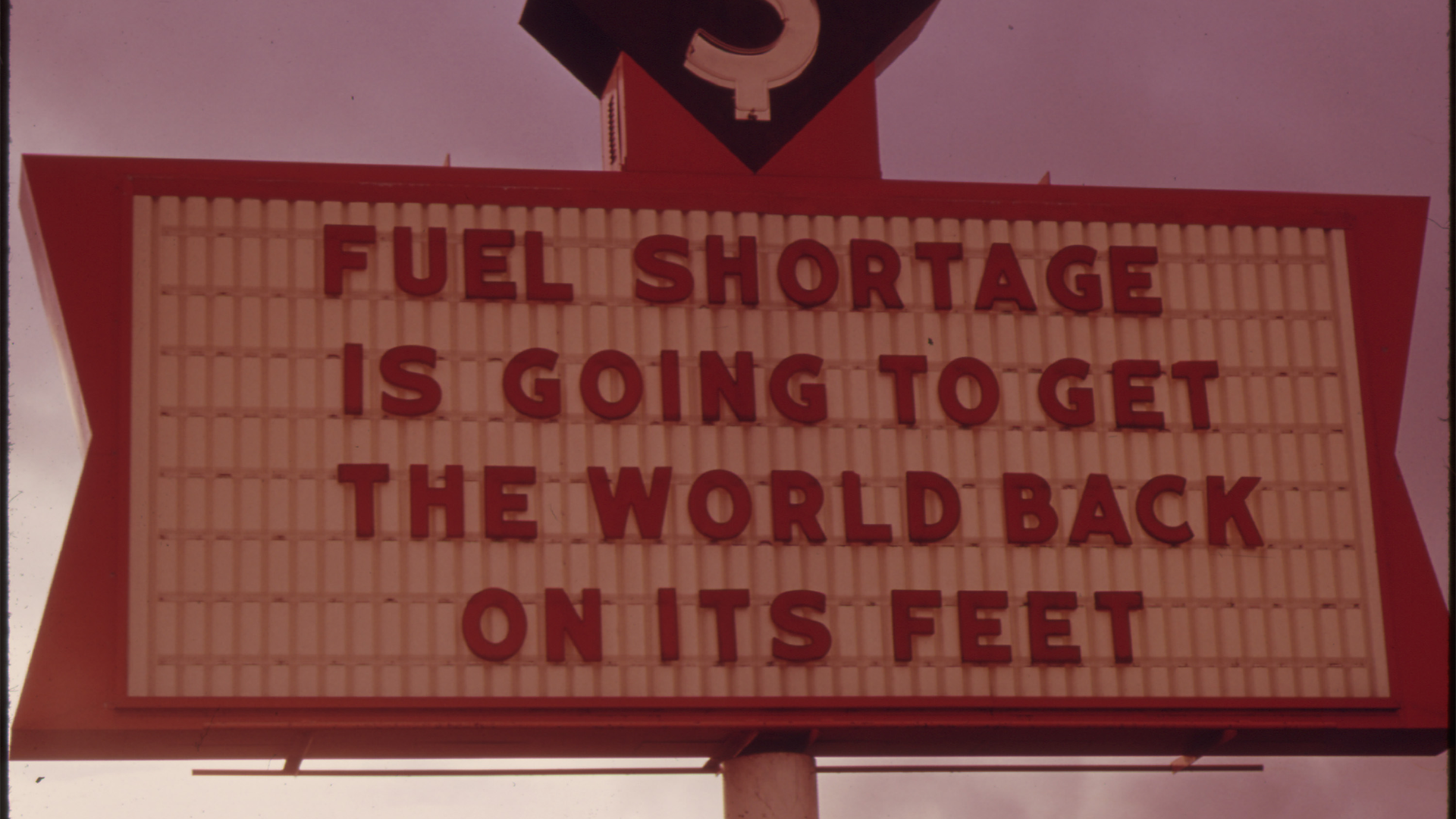

Fuel shortages darkened signs like this one in Vancouver, Washington. Photo credit: Falconer, David, photographer. The Energy Crisis in the States of Oregon and Washington Resulted in Attempts at Humor By Businesses with Darkened Signs Such As This One in Vancouver, Washington, 1973. Photograph. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/555423.

1970s-The Energy Crisis & Space Travel

Delighted with the mass availability of automobiles, Americans moved into the 1970s. Popular songs from many genres speak to the proliferation of vehicles celebrating life on the road-Truckin’ (Grateful Dead, 1970), I’m in Love with My Car (Queen 1975)-and the importance of local roads-Take Me Home, Country Roads (John Denver, 1971). However, an energy crisis significantly changed Americans’ relationships with their cars. In 1973, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) responded to the US backing of Israel in the Yom Kippur War by implementing an embargo on exports to the United States. Oil prices ballooned by more than 350 percent, sending the US economy into a sharp downturn, with both inflation and unemployment skyrocketing upwards. Scarcity fears caused hours-long gas lines, and public advertising campaigns sought to convince Americans to conserve energy at home and on the road.

Delighted with the mass availability of automobiles, Americans moved into the 1970s. Popular songs from many genres speak to the proliferation of vehicles celebrating life on the road-Truckin’ (Grateful Dead, 1970), I’m in Love with My Car (Queen 1975)-and the importance of local roads-Take Me Home, Country Roads (John Denver, 1971). However, an energy crisis significantly changed Americans’ relationships with their cars. In 1973, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) responded to the US backing of Israel in the Yom Kippur War by implementing an embargo on exports to the United States. Oil prices ballooned by more than 350 percent, sending the US economy into a sharp downturn, with both inflation and unemployment skyrocketing upwards. Scarcity fears caused hours-long gas lines, and public advertising campaigns sought to convince Americans to conserve energy at home and on the road.

Amtrak, for example, ran a series of campaigns promoting rail as a more fuel efficient (and affordable) alternative to driving. By the middle part of the decade, we see modes that likely reflect the nation’s reconsideration of travel sparked by the energy crisis: Midnight Train to Georgia (Gladys Knight and the Pips, 1973), Jet Airliner (Steve Miller Band, 1977), and Come Sail Away (Styx, 1977). Some folks even began biking to work to save money on gas. Queen’s 1968 Bicycle Race uses the simplicity of bicycling to avoid the political and cultural controversies of the 1960s and 1970s:

I don’t wanna be a candidate

For Vietnam or Watergate

‘Cause all I want to do is

“¦

Bicycle, (Yeah) bicycle, (Hey) bicycle

I want to ride my bicycle, bicycle (c’mon), bicycle

I want to ride my bicycle

I want to ride my bike

I want to ride my bicycle

I want to ride it where I like

-Queen, Bicycle Race (1978)

Image: Gas shortages and rationing of the 1970s meant that stations would often run out of fuel. Photo Credit: Warren K. Leffler, 1974. https://www.loc.gov/item/2018654069/

Even as American consumers felt the squeeze of fuel costs, transportation technology was pushing new frontiers in outer space. The United States sent the crew of Apollo 11 to the moon in 1969, and during the 1970s, NASA continued its Apollo programs, built the Skylab space station (1973), and launched the spacecrafts Voyager I and II (1977). The Voyager missions carried the famous Golden Record to share the sounds of daily life, languages, and music on Earth with other intelligent life forms. All things space and NASA proliferated in popular culture, propelled by shows like Star Trek and found its way into popular music, especially progressive pop and glam rock which explored the boundaries between Earth and space, with David Bowie’s 1969 Space Oddity album and Elton John’s 1972 Rocket Man.

Even as American consumers felt the squeeze of fuel costs, transportation technology was pushing new frontiers in outer space. The United States sent the crew of Apollo 11 to the moon in 1969, and during the 1970s, NASA continued its Apollo programs, built the Skylab space station (1973), and launched the spacecrafts Voyager I and II (1977). The Voyager missions carried the famous Golden Record to share the sounds of daily life, languages, and music on Earth with other intelligent life forms. All things space and NASA proliferated in popular culture, propelled by shows like Star Trek and found its way into popular music, especially progressive pop and glam rock which explored the boundaries between Earth and space, with David Bowie’s 1969 Space Oddity album and Elton John’s 1972 Rocket Man.

Image: The South of Earth golden record. Image credit: Carter, Jimmy, Kurt Waldheim, and United States National Aeronautics and Space Administration. The Sounds of Earth, 1977. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/cosmos000115/.

Ground Control to Major Tom

Ground Control to Major Tom

Take your protein pills and put your helmet on

(Ten) Ground Control (Nine) to Major Tom (Eight, seven)

(Six) Commencing (Five) countdown, engines on

(Four, three, two)

Check ignition (One) and may God’s love (Lift off) be with you

-David Bowie, Space Oddity (1969)

Transportation music of the 1970s reflect the modes of a rapidly changing society and changing perspectives, particularly an increasing awareness of the fragility of a transportation network built entirely on gasoline-powered automobiles.

Just getting to the 1970s has taken us a long way, but our history of transportation music is not done yet. Read the next installment of this series for the 1980s, 1990s, 2000s, and today!