May 3, 2022

6 Ways Cities Are Building and Maintaining Bike Infrastructure That Lasts

On September 14, 2018, Hurricane Florence made landfall in Wrightsville Beach, NC. Over the next four days, the slow-moving storm dumped record amounts of rainfall across the Carolinas. Parts of North Carolina recorded 35.93 inches, a record for the state’s highest rainfall total ever recorded from a tropical storm.

200 miles east, as Charlotte’s creeks swelled and overtopped their banks, social media photos circulated of people kayaking in areas previously occupied by intermittent streams and greenways that are popular with bicyclists.

Unfortunately, due to the increasing number and intensity of hurricanes and summer thunderstorms, these scenes of flooded bikeways were familiar to Charlotte’s transportation planners and engineers. The Charlotte Department of Transportation (CDOT) was already in the midst of a large effort to rethink the City’s approach to bicycle planning and infrastructure investment.

CDOT’s Spatial Analysis of Bike Network Resiliency During Rain Events

CDOT decided to complete a simple GIS spatial analysis to investigate the resiliency of their existing bike network, and the results were surprising.

Charlotte’s bike network is heavily reliant on a system of creekside greenways. As a result, roughly 25 miles of Charlotte bikeways disappear under water during minor rain events (13% of its total network).* In major rain events, Charlotte loses 44 miles of bikeways, or roughly 24% of its total bike network. Imagine the uproar if 13%-24% of a city’s total lane miles for cars disappeared underwater every time it rained!

*For the spatial analysis, CDOT planners used the “floodway” level as a minor rain event and the “500-year floodplain” as a major rain event. The term “500-year flood” was born out of the National Flood Insurance Program in the 1970s and does NOT reflect the actual frequency/history of floods nor the reality of increasingly severe and frequent rain events. Recognizing that the term “500-year flood” is an antiquated indicator, the study team instead used the term “Major Rain Event” to avoid confusing the public about the actual frequency of these events.

For decades, cycling has been recognized as a key part of supporting climate resilience. Safe and comfortable bikeways as an alternative choice to driving make our cities less polluting, more livable, and more resilient. But what happens when the bicycle networks we depend on to help support urban resilience aren’t themselves resilient to climate events? Read on for some of the biggest resiliency challenges facing our bike systems today, and six specific ways cities are tackling these challenges.

What happens when the bicycle networks we depend on to help support urban resilience aren't themselves resilient to climate events?

Challenges to Bike Infrastructure During Weather Events

Rain

Many U.S. cities were historically built around waterways to facilitate transportation of goods and services. This means that many of our cities are close to sea level in climates with plenty of rain. While this makes for lovely waterfront views and recreation, it also means our cities are prone to flooding. Sea level and severe rain events are on the rise, flooding our city streets and greenways and inhibiting bicycling. These specific challenges include:

- Flooding on waterfront greenways. The waterfront greenway is uniquely susceptible to flooding for obvious reasons.

- Debris in on-street bicycle facilities. On-street bicycle facilities also face challenges during rain events. Streets are typically designed with a “crown,” a high point sloping down to curbs at either side. Most of our bike lanes are located at the curb in an area referred to as “the gutter” by traffic engineers. And, like the gutter along the side of your roof, street gutters (and thus bike lanes) become clogged with debris carried by draining stormwater.

- Oversized street sweepers. Standard street sweepers do not fit within one-way, separated bike lanes, meaning storm debris can remain an unsightly hazard for days, weeks, or even months depending on the frequency of sweeping.

- Puddles and slippery surfaces. Curbside bike lanes leave people on bikes saddled with the brunt of flooding. Imperfections in pavement or simply high-intensity rain result in large puddles, which are difficult to bike through and can be dangerous when unexpected. Utility structures (“manholes,” handholes, and catch basins) are often located within bike space and can be a slipping hazard when wet.

- The splash zone. Bike lanes near to vehicle travel lanes, curbside or otherwise, leave people biking vulnerable to unsolicited showers from their fellow road users.

Snow

As you head north, new difficulties arise from snowfall and freezing temperatures. Many on-street bicycle facilities require extra care when dealing with issues such as:

- Snow buildup. Bike lanes are often the de facto storage area for snow that has been cleared from vehicle travel lanes. Or, where on-street parking is present, snow is plowed to the curb, pushing parked cars out into bicycle lanes and rendering them useless.

- Snowplow challenges. When bike lanes are separated from moving vehicles, they can be inaccessible to standard snowplows due to insufficient clearance between separators and curb. When separated bike lanes do accommodate standard plows, the plows lack the precision needed to provide a clean clearing. Instead, they leave behind a slick, compacted layer of snow ripe for a slip followed by a hard landing.

- Flattened flexposts. The most common method of separation for bike lanes is the flexible delineator, and plow operators often crush these when clearing snow from the bike lane or adjacent vehicle lanes. The little separation provided for cyclists is now gone after the first storm of the winter, an all-too-common story for winter cyclists. In fact, this has been used as justification for removing physical separation from on-street bike lanes during winter months.

- The freeze-thaw cycle. Prolonging the impacts of winter precipitation is the freeze-thaw cycle. As temperatures rise during the day, snow melts and pools on the street. Come night, temperatures drop below freezing, and the snow turned water now turns ice. This not only creates a slipping hazard for cyclists, but also is the cause of New England’s infamous potholes.

Bike infrastructure across the country is facing these and other challenges associated with rain and snow. At the same time, many cities are stepping up to the challenge and strategically making their bicycle networks more resilient. Here are six specific ways they’re doing that.

The Ingredients of a Resilient Bike Network

#1: Have a Plan for Floodprone Bikeways

The Mecklenburg County Park & Recreation Department maintains Charlotte’s creekside greenways. After the flood waters from Hurricane Florence subsided, Mecklenburg County maintenance staff quickly began to clear all of the silt and debris and make necessary repairs to the greenway system. They’ve built speedy greenway maintenance into their mission and culture.

The County’s maintenance crews know exactly how high creeks must rise to overtop greenways and exactly which culverts and low-lying areas historically/routinely flood. They use a combination of monitoring equipment, video cameras, and field crews to patrol greenways during rain events. When greenways flood, they know about it and can begin responding before most residents emerge from under their roofs and umbrellas.

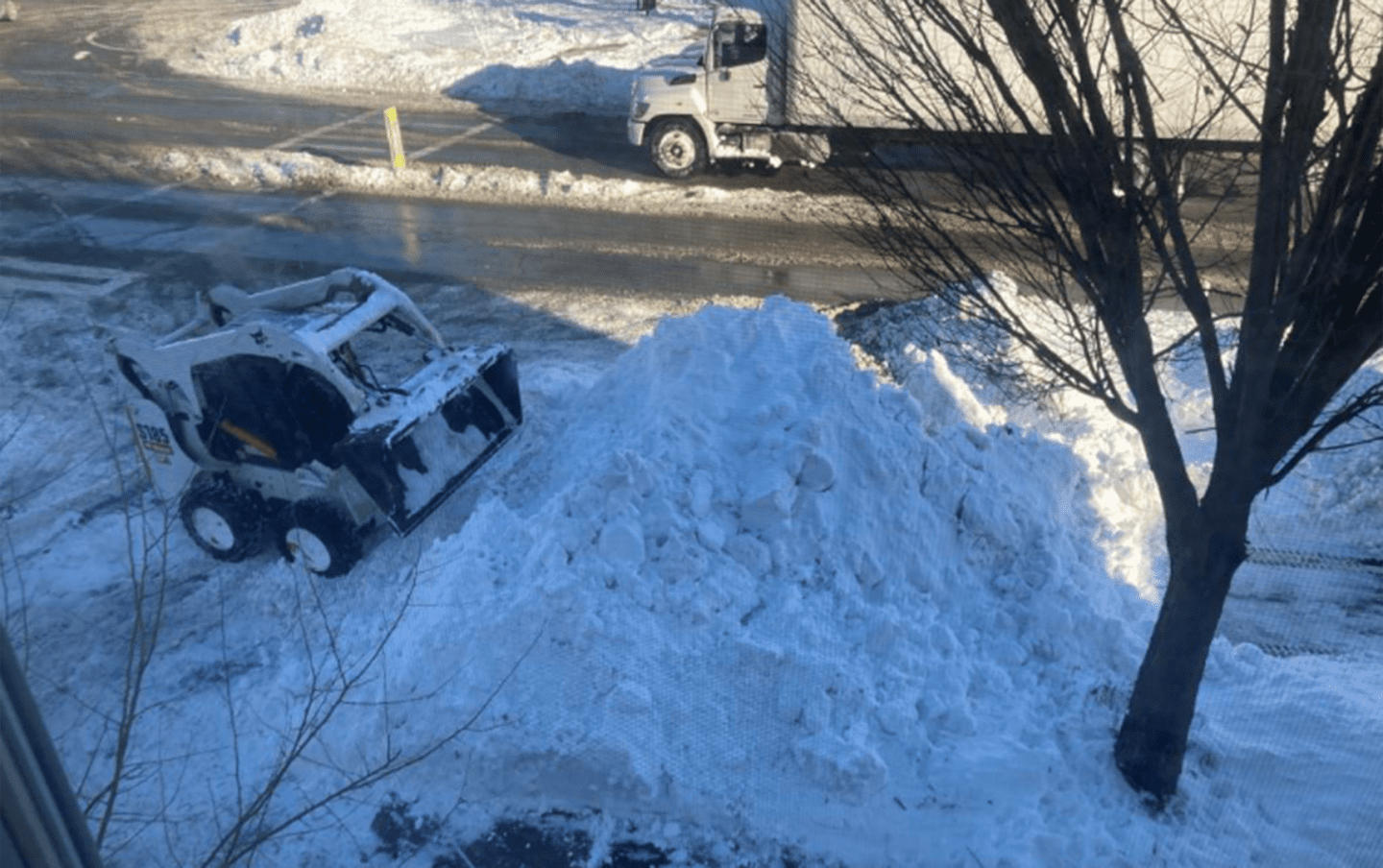

These crews use small skid steer tractors to remove sediment and debris from greenway surfaces. This is immediately followed with squeegees (handwork) to clear the fine sediment that the tractors can’t get. If major structural damage is done to asphalt or concrete, third-party contractors are brought in to make repairs. Sometimes their commitment to maintenance prompts County staff to go even further. After a major flood event that washed out a mile of natural surface greenway along Mallard Creek, staff laid down recycled asphalt, graded and compacted it, and had the greenway open again in just three days.

All of this contributes to a Departmental goal of having greenways clear and operational within 48 hours after a flood event – a goal that is very often exceeded. They are currently researching new equipment to make this whole process even more efficient. (Special thanks to Michael Monroe, Mecklenburg County Greenway Operations Manager, for the insight on Mecklenburg County’s greenway maintenance protocols, and to his staff and partners for their hard work keeping greenways clean and tidy!)

Pictured above: A *VERY* rare photo of the aftermath of a rain event on the Little Sugar Creek Greenway. Mecklenburg County Greenway Staff have implemented a maintenance plan that typically results in greenways being cleared less than 48 hours after flooding (making photos like this exceptionally difficult to get).

#2: Invest in Your On-Street Network

Perhaps one of the simplest ways to make a bike network more resilient to increasingly severe and frequent rain events is to build more on-street infrastructure. When safe and comfortable cycling options are available on-street, flooded greenways don’t shut down the whole bike network. A true cycling network includes redundancies. When one segment of the network is impassable, people biking need a nearby, parallel link that is convenient, safe, and comfortable.

In Charlotte, Hurricane Florence coincided with the preparation of the City’s Uptown CycleLink Feasibility Study & Concept Plan. The Uptown CycleLink is an on-street, separated bike lane network in downtown Charlotte (which Charlotteans call “Uptown” because it sits on high ground between two creeks). The CycleLink is a bold vision that will retrofit roughly seven miles of streets in the densest urban environment in the Carolinas with two-way separated bike lanes that are safe and comfortable for users of All Ages and Abilities (AAA bikeways). The flooding from Florence added a sense of urgency to the Uptown CycleLink as planners’ sought to connect greenways and establish AAA bikeways in areas that are not as susceptible to flooding.

Kittelson is leading the planning and design of the Uptown CycleLink in Charlotte, NC. Photo Credit: Grant Baldwin Photography, courtesy of Sustain Charlotte

The Uptown CycleLink will retrofit ~7 miles of streets, in the densest urban environment in the Carolinas, to include separated bike lanes that are safe and comfortable for cyclists of All Ages and Abilities (AAA bikeways).

#3: Consider Raised Facilities

There is no panacea for the specific challenges that climate change poses for our bike networks, but raised bike facilities (or raised cycle tracks) come close.

Raising bicycle facilities to the sidewalk level keeps accumulated street debris and stormwater out of cyclists’ paths. Often raised bike facilities are designed to drain into the street or an adjacent planter, and don’t require separated stormwater drainage. When separate drainage is required, drains can be small and placed outside the travel path of people biking.

A cycle track on Somerville Avenue in Somerville, MA is constructed with small drains placed outside the primary path of cyclists for rider comfort and safety.

A cycle track on Kooiksersweg (Kooiker Road) in s'Hertogenbosch, NL constructed with a depressed slot drain running parallel on the right and separated from vehicles by shrubs and trees on the left. Photo Credit: Bicycle Dutch

Similarly, after snow accumulation, melted snow will not pool in a raised cycle track as it does in curbside bike lanes. Therefore, when temperatures drop below freezing, there is far less potential for ice to form in the bike space.

Raised cycle tracks also bring benefits beyond drainage. Raised bike facilities are much less likely than on-street facilities to be viewed as de facto snow storage areas for snowplow operators. Additionally, grade separation and curbs are more robust than flexposts and are not as vulnerable to plowing operations as flexposts. Raised cycling facilities can also serve as a shared space for cyclists and pedestrians in the interim as residents and public works crews work to remove snow from sidewalks. All of this makes for safer walking and biking during snowstorms as many people need to make essential trips.

Often, width constraints are used as a primary justification for not providing a raised, street-side bike facility. However, separated on-street bike lanes occupy the same width, or sometime more, than the width necessary to construct a raised cycle track. A more significant question is whether municipalities are willing and able to invest in the full design and construction of raised facilities. For an increasing number of cities recognizing the livability, sustainability, and equity benefits of raised bike infrastructure, the answer is a resounding yes!

#4: Obtain Specialized Maintenance Equipment and Training

We cannot reconstruct all city streets in the near-term, but we can expand our bike networks more quickly with “paint-and-post” facilities. Acknowledging this reality, we can implement maintenance solutions to minimize the negative externalities of quick-build facilities.

To mitigate the buildup of debris in curbside bike lanes, cities can procure specialty sweepers, sized and nimble enough for pedestrian and cycling infrastructure. As cities expand their networks, they should likewise expand their fleet of maintenance vehicles for these facilities. With vehicles less than five feet wide, street width is less of a constraint when determining where new bicycle facilities can be implemented.

Pictured right: a Tennantâ„¢ street sweeper used by the City of Cambridge Department of Public Works (DPW) to maintain their network of protected bicycle facilities. Photo Credit: Alexander Epstein/U.S. DOT Volpe Center

Pictured right: a Tennantâ„¢ street sweeper used by the City of Cambridge Department of Public Works (DPW) to maintain their network of protected bicycle facilities. Photo Credit: Alexander Epstein/U.S. DOT Volpe Center

The same goes for winter maintenance (i.e. snowplowing) of bike lanes. While Bobcatâ„¢ loaders and some pickup trucks equipped with plow blades can fit in many separated bike lanes, they cannot match the precision of smaller, specialty plows and rotating brush attachments.

This equipment can make all the difference between having a compact, refreezing layer of snow and ice and having a clear, smooth path, free of slipping hazards. Rotating brush attachments and sharper, straighter blades leave behind bare or near-bare pavement for a smooth ride and no snow layer to refreeze into a hazardous riding surface.

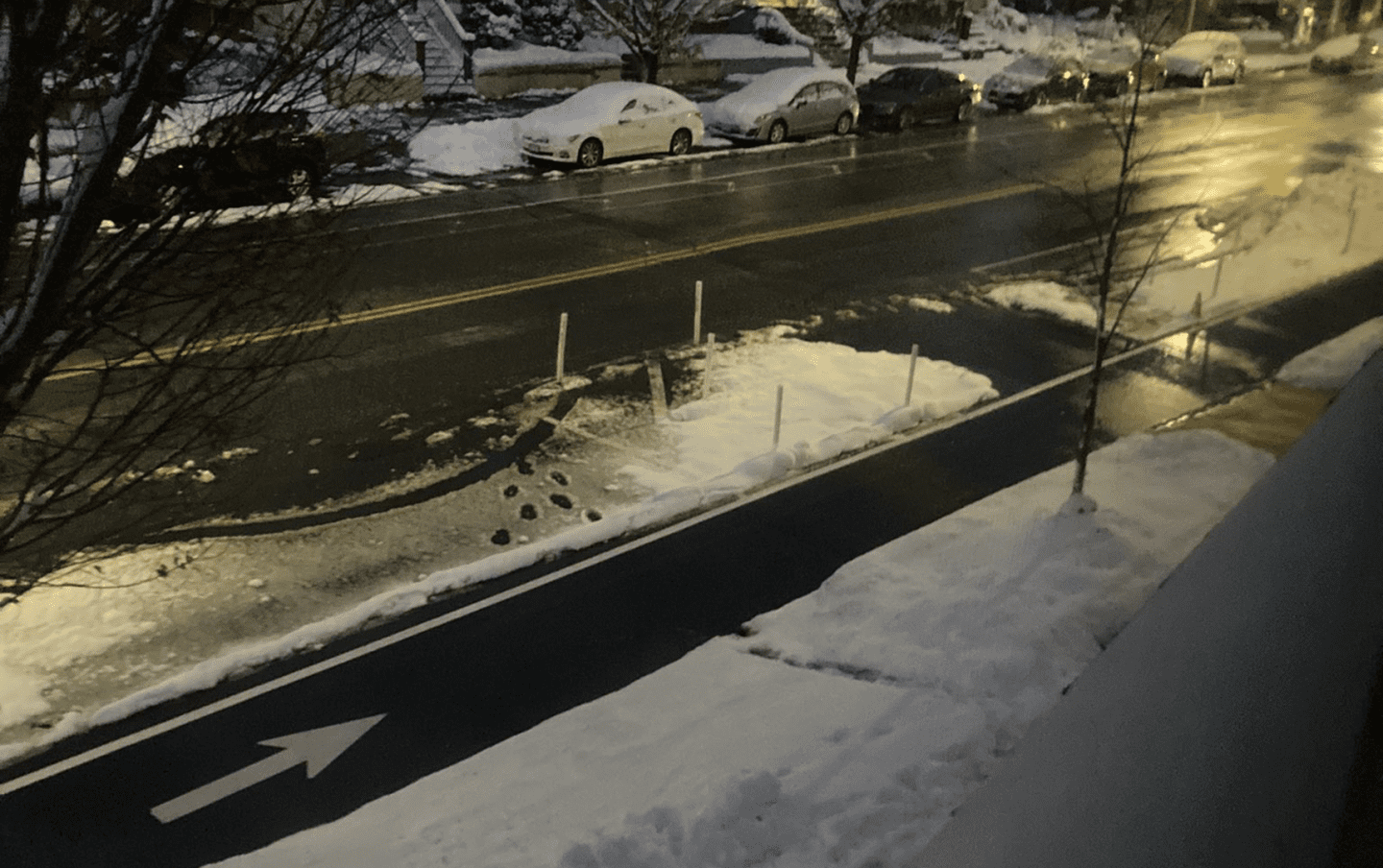

Just as important as equipment is people. Education of public works personnel on bicycle facilities and best practices for clearing them of snow is key in successful winter maintenance, especially in jurisdictions employing independent contractors like those in the greater Boston area. Without necessary training, bike lane entrances and pedestrian ramps often end up completely obstructed by towers of plowed snow because the intersection (i.e. the end of each block) is a natural place for plow operators to pile snow.

A Bobcatâ„¢ operator dumps snow in a massive pile that blocks the entrance to a parking-protected bike lane on Broadway in Somerville, MA.

The same bike lane cleared after Public Works sent the contractor back to correct their mistake more than 24 hours later.

#5: Empower Citizen Heroes

Sometimes your neighbors are your best maintenance partners. Leaning on eager volunteers to support bikeway maintenance can be a winning strategy that reduces the burden on public agencies and empowers cycling advocates to get involved in productive ways. When greenways are impacted by flooding, Mecklenburg County engages volunteers to clean wooden boardwalks and sections of greenways where heavy equipment can’t go.

Also in Charlotte, the Plaza Midwood Neighborhood Association maintains the planters that are used as vertical buffers for a separated bike lane on a major connector street and bicycle route called “The Plaza.” The neighborhood association formalized their role by signing an agreement with the City’s Right-of-Way Management group that requires them to maintain the plantings and reset any planters that are dislodged by cars or vandals. That commitment from the neighborhood association gave the City the assurances it needed to cover the up-front costs and install the planters as a part of the separated bike lane project.

#6: Construct Bike Lanes with Resiliency in Mind

Resilient bike facilities can directly slow climate change. Projects featuring cycling infrastructure are an opportunity to reduce overall impervious surface area and add to your urban canopy.

For example, when designing a raised cycle track, include buffer space on either side. This space does not need to be barren, impervious concrete that necessitates more drainage capacity and exacerbates the urban heat island effect. Instead, seize the opportunity to add street trees, shrubs, and even full-blown bioswales.

Permeable pavement is also a tremendous tool that reduces runoff, is more resilient to freeze-thaw cycles, and less prone to icing over after snow begins to melt in the winter. Permeable pavement allows water to infiltrate into the ground below, which replenishes groundwater while filtering pollutants. With melting snow infiltrating the surface, it freezes below the surface rather than in the path of bicyclists. Additionally, because permeable pavement is porous and comprises substantial void space, it allows water to freeze and expand without creating cracks and potholes.

A cycle track on Somerville Avenue in Somerville, MA is constructed with permeable pavement and adjacent vegetation for increased infiltration and reduced runoff.

With designs like these, fewer maintenance resources need to be dedicated to sanding and salting bicycle facilities in the winter, and public works agencies can greatly reduce their salt pollution, preserving soil, groundwater, surface water, and protecting bikes from rust. Moreover, cities can reduce the need for traditional, costly drainage systems and beautify their streets.

Conclusion

Resilient bike infrastructure is one of the cornerstones of a resilient transportation network, and thus a resilient community. It’s well worth our time to consider the unique challenges to bikeways in the face of rain and snow, and how we can strategically plan, construct, and maintain this infrastructure to keep it safe and operable for the people that use it now, and encourage more people to use it in the future.

There’s much more to discuss when it comes to this topic, and we encourage you to reach out to either of us to keep the conversation going!