August 9, 2023

What captures your interest more: “corridor plan” or “neighborhood greenway”? Both may describe the same project, but the latter may be more likely to inspire the public to read on.

The truth is that the studies, reports, and other deliverables that help actualize projects in the real world, while essential, can be dry to read. What these documents provide in specificity, expertise, and instruction, they often lack in approachability and human perspective. Preparing these materials using the principles of approachability, empathy, and plain language can help a community understand how a project impacts them and can therefore bolster support for it.

Kittelson’s team of technical writers use storytelling skills to translate highly technical reports into readable, charismatic documents that engage community members and industry readers alike. These editors draw upon their experiences in journalism, academic writing, and creative writing to foreground a project’s why in addition to its how. But what does it look like to develop technical material using the tools of storytelling? What are the ultimate benefits of this approach? Read on to find out.

Preparing project reports using the principles of approachability, empathy, and plain language can help a community understand how a project impacts them, and can therefore bolster support for it.

Once Upon a Time”¦

When we talk about “storytelling,” we don’t really mean opening the latest NCHRP report with a roundabout far, far away. The deliverables produced and edited by the technical writing team still resemble professional, specialized communications more than they resemble novels or journalistic nonfiction.

Although we may think of it primarily as a form of escapism, storytelling is in fact a highly effective argumentative mode. A wealth of evidence suggests that storytelling owes its unique persuasiveness to the way it activates the listener’s brain. Narrative engages not only the parts of the brain associated with language processing, but also the parts associated with feeling and movement. This combination of persuasiveness and escapism – the qualities that make storytelling such an appealing rhetorical mode to audiences – lend it readily to political messaging and advertisements. It’s worth examining the ethical grey area of using the sly machinery of storytelling to make arguments, and how we’re managing that terrain in a way that feel transparent and is rooted in fact.

Consider the narrative copywriting that performs canny sleights of hand in brand advertising. Often, these narratives equate consumer purchasing power with moral virtuousness. The lyricism of Coca-Cola’s 1971 “Buy the World a Coke” ad aside, global harmony doesn’t really depend on the mass proliferation and consumption of soda. Similarly, Apple’s world-shaking “1984” ad suggests that the purchase of an Apple Macintosh computer will liberate the consumer from IBM’s technological tyranny, when in fact the purchase only swaps out one corporate overlord for another. Even Bert Thomas, an art director who worked with Apple on the commercial, understood the ad’s tortured argument and attempted, after its airing, to hedge on the messaging in a New York Times article. “We did not say the computer will set us free,” Thomas states (although this is exactly what the ad says). “This was simply a marketing position.” It’s not that this type of advertising is inherently unethical-“there may be some value in letting a viewer know that it’s okay to want to drink a Coke-but it plays on human emotion to convert materialism into a moral imperative where formerly none existed.

While it’s important to note that our technical writing also leverages human emotions to deliver its point, it does so in a different way and to different ends. Instead of artificially generating an emotional association to a neutral product, the technical writing team uses storytelling techniques to remind audiences that a subject that is too frequently depicted as an impersonal fact – transportation – is in fact a very personal facet of life for many users. We draw upon this emotion to ground the issues and important questions revealed by empirical data and community input in a human framework. This narrative work shares more in common with initiatives to add storytelling to American healthcare than it does with brand advertising: instead of manufacturing importance that isn’t there, we aim to expand the reader’s awareness of why something is important.

Storytelling in deliverables isn't about manufacturing importance that isn't there. It's about expanding the reader's awareness of why something is important.

The Tools of the Trade

Practically speaking, how do we use storytelling principles within transportation deliverables? Read on to learn how to use structure, arc, and setting to craft messages that inspire appropriate emotion and action.

Structure

Conventional literary narrative shape dictates that a story should begin with an inciting incident, spend its middle escalating the conflict, and end with climax and resolution. Readers have consumed a lifetime of stories that follow this structure. Configuring reports and public-facing deliverables to mirror this shape can make them easier to follow. We begin by identifying a problem, elaborate on an approach or methodology used to address that problem, and end by arguing that certain recommendations will best solve for the need identified.

Additionally, narrative deliverables complement this three-act structure with structuring mechanisms used in contemporary journalistic storytelling. This style of storytelling increasingly favors clear visual hierarchies that make key takeaways easy to digest for readers.

The visual hierarchy tiers information to accommodate many types of readers. The skimmer seeking only the key stats will still get a clear idea of the project’s story just by scanning the headers, pull quotes, and visuals. Meanwhile, the longform reader who wants a comprehensive understanding of a project’s methodology can work through the body text.

An old newspaper features small, hard to read text that densely fills the page, making it difficult for the eye to know where to rest. (This probably reflects the reality of the time: print was expensive, and there was less competition for readers.)

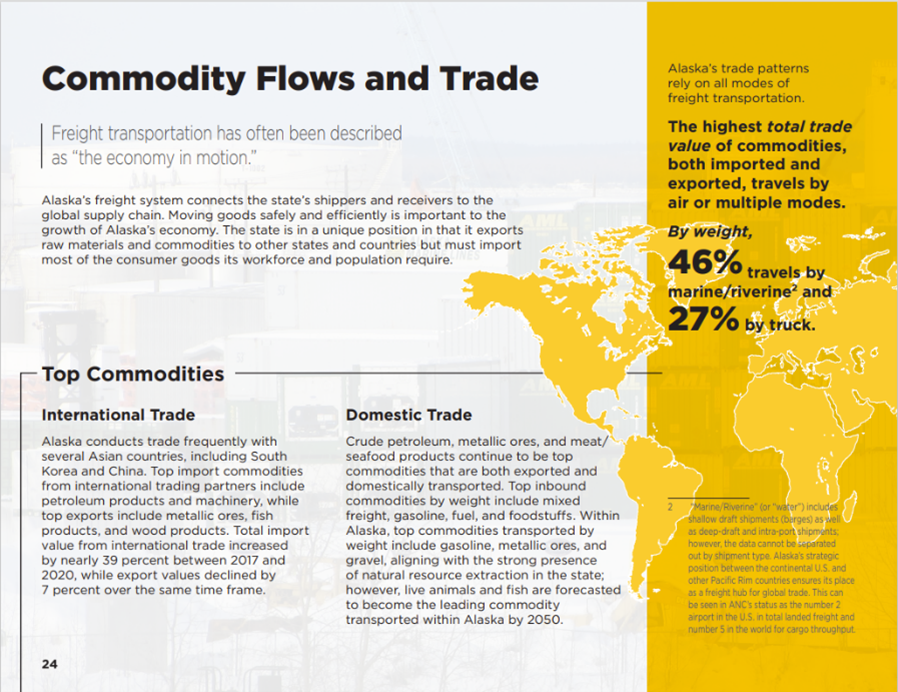

In contrast, this image from the Alaska Moves 2050 Statewide Freight Plan, uses varying text sizes, colors, and images to help the reader more intuitively understand how they should absorb and interpret the information.

This approach does more than present information in a logical order and in a range of levels of detail. It also takes into account the way readers have been increasingly conditioned by high-volume shortform content – social media posts, many blogs, and smartphone-optimized user experiences – to absorb material, and then tailors deliverable content to operate in accordance with that hardwired expectation.

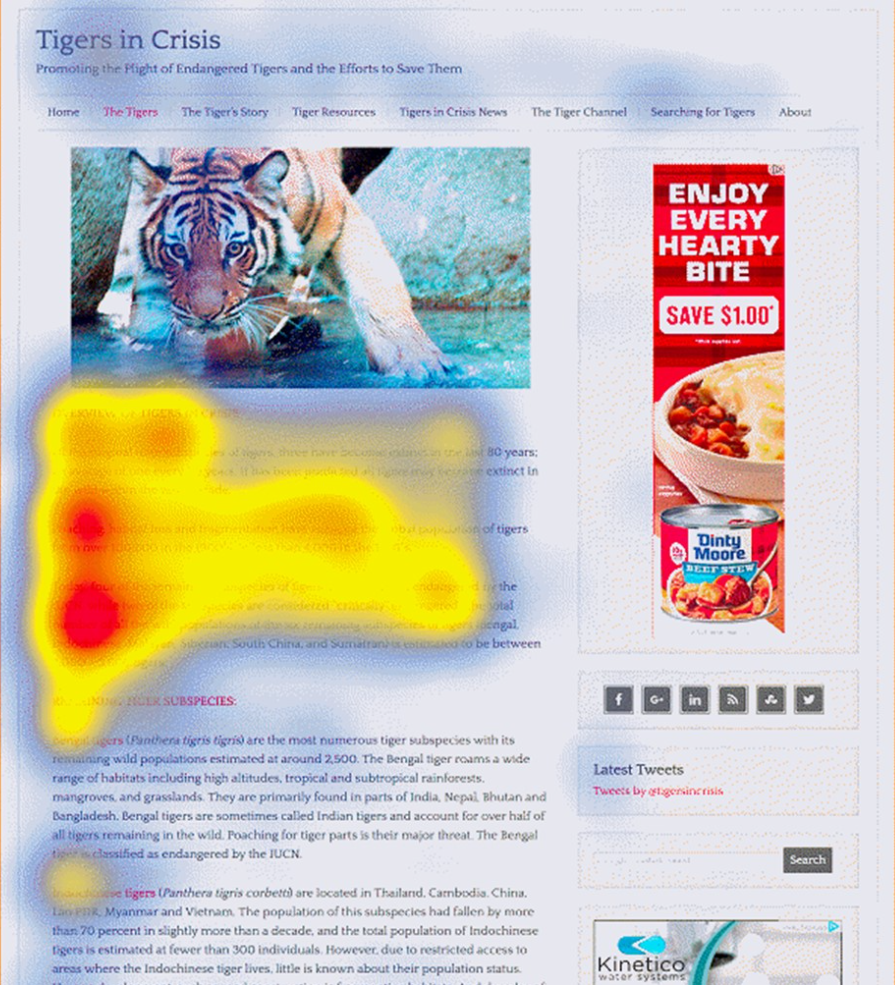

Laying out content on the page to match well-known eye-activity patterns (like the F-shaped reading pattern, shown below) can help ensure the reader will be exposed to a page’s most important points.

Many readers naturally tend to skim in an F-shaped reading pattern, shown above on the heat map. (Image: Nielsen Norman Group)

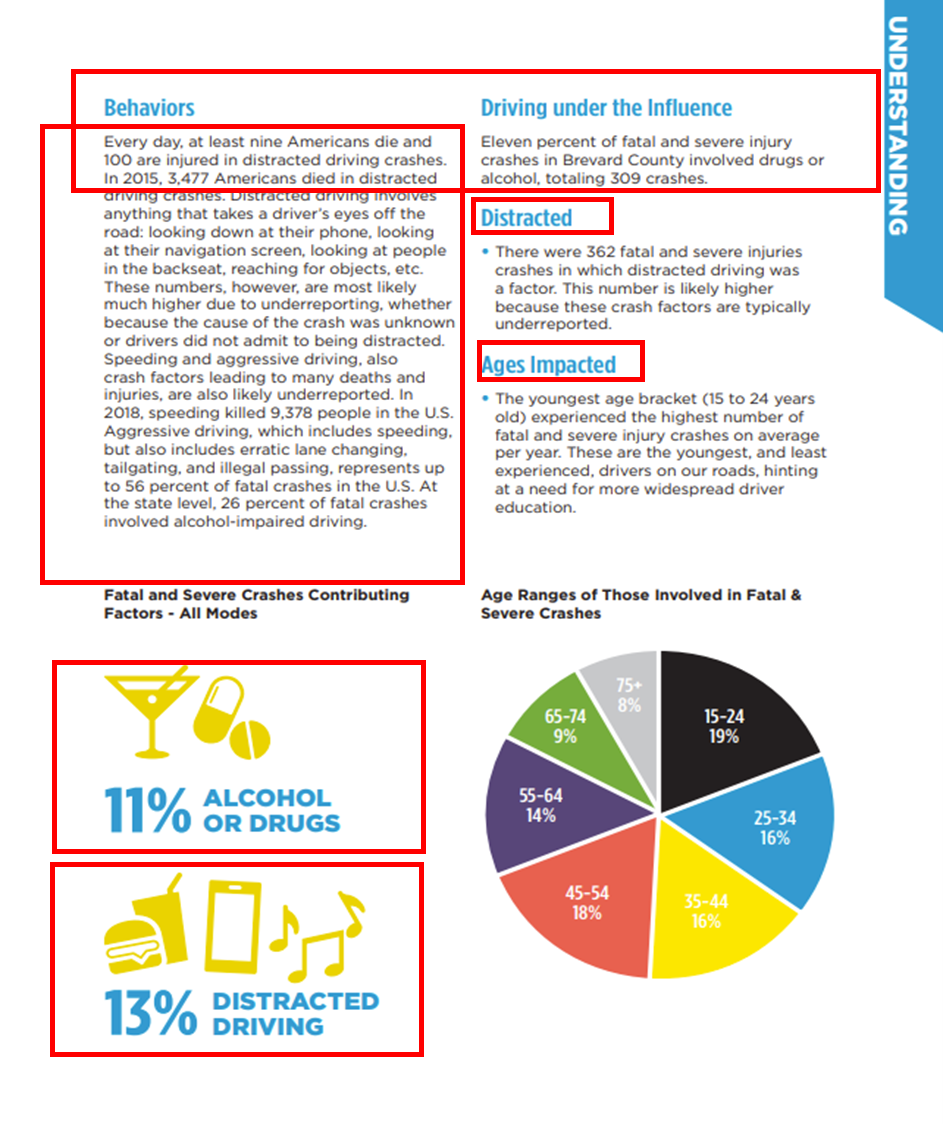

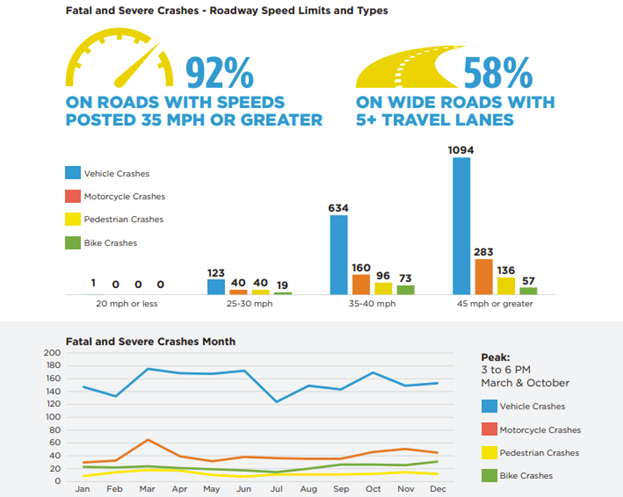

Space Coast TPO's Vision Zero plan, shows how technical writers can take advantage of this by formatting important material in this same shape on the page. (Image: Space Coast TPO)

On the other hand, laying out content in dynamic compositions can also influence how the reader’s eye moves across the page. Below, the paneled configuration of the page at once moves the eye down the page in layers (the “layer cake” scanning pattern) while also keeping the information neatly organized by topic.

Segmenting information into stacked blocks can help the eye move in an orderly manner down the page and encourage the reader to spend more time with each individual unit of meaning than in the F-shaped pattern. (Image: Nielsen Norman Group)

The above page, taken from Space Coast TPO's Vision Zero report, stacks the information in clean layers to guide the eye, making the myriad of figures easier to attend to individually. (Image: Space Coast TPO)

These instances demonstrate the reflexive nature of structure’s role in comprehension: it at once fulfills the reader’s longstanding and preformed expectations while also influencing those expectations as they move through the document. Ultimately, these journalistic storytelling tools do more than facilitate the reader’s ability to interpret the deliverable as it moves through a familiar three-act structure; they actively perform some of the interpretive labor on the reader’s behalf by visually emphasizing the document’s most important points.

Arc

Arc

In fiction, an arc structures a story by helping the audience make sense of the events of a plot and the choices of a character. Typically, we talk about “arc” as something a character has. For example, an antihero has a redemptive arc; they rise over the course of a narrative from disgrace to dignity. But how can a State’s application for HSIP funds have an arc when it has no characters? Are the highways supposed to be our protagonists? “Arc” might seem like an integral element of storytelling, but its dependence on character makes it seem at first glance like a tougher fit for technical writing.

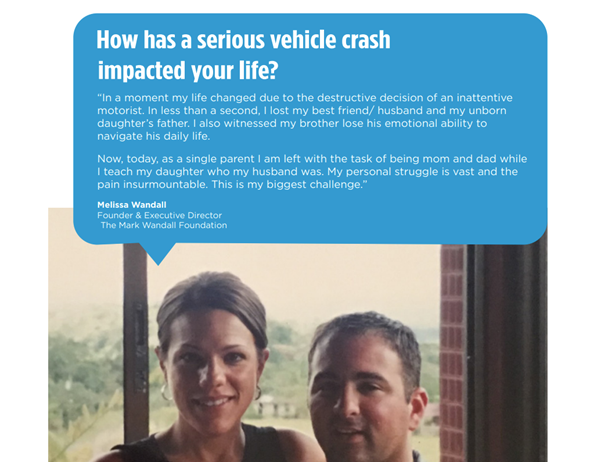

However, in specific instances, human characters are not only relevant but integral to a document’s purpose. Vision Zero plans, which communicate to local leaders and the public the importance of adopting Safe Systems countermeasures to protect human users, draw upon real-life testimonials from people who have lost loved ones in traffic crashes or who were themselves seriously injured in a crash. These testimonials contrast the individual’s life before and after the accident to punctuate the way crashes can interrupt, and sometimes forever alter, the assumed trajectory of a person’s life.

These testimonials give vital emotional weight to documents. They also represent in a contained segment how narrative deliverables organize themselves on a macro level. These stories reflect the larger document’s tendency to contrast the “before” project conditions with “after” project conditions; this transformation helps the reader to understand the arc of the project in its community.

Setting and Context

Setting and Context

Taking the time to describe the texture and history of a project’s place can also help to bring that project’s story to life. The literal roadways affected by a project might not have much character, but the landscapes and communities they cut through always do. Just as New York City is the secret fifth protagonist of Sex and the City, setting can act as a character worthy of the audience’s attention in deliverables.

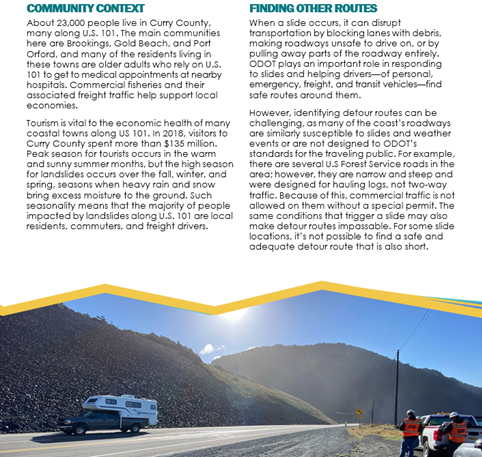

The sample on the right comes from a report prepared for the Oregon Department of Transportation and discusses contingency countermeasures for the growing threat of landslides along the Oregon coast. The page pairs 1) an image depicting the relevant “problem” topographical conditions (manmade roadways imposed at the base of winding coastal hills); 2) community information on how people use the space (“Community Context”); and 3) the human toll that occurs when landslides interrupt this usage (“Finding Other Routes). By understanding a community’s spatial needs, and extending this understanding to a specific project site, the document builds a dramatic stake around a non-human entity.

Heart-to-Heart

These techniques work together to recontextualize a technical project into terms better appreciated by the reader, who may not possess any technical training in transportation planning. The power of storytelling in project deliverables is twofold:

1) These techniques make the stake of the project clear to the audience. Visual hierarchy, arc, and setting can all provide readers with a richer understanding of the “problem” the deliverable and its associated project exist to address. This understanding deepens the reader’s appreciation for the project and – more subtly – their investment in the document. We think of the best narratives as those that contain surprising, unexpected twists, but consider that an ending can only “twist” if we first envisioned it would end some different way.

Even without a twist, narratives still create suspense and audience interest by signaling early on what their climaxes will look like – after all, we can only anticipate what we can expect. In The Lion King, when Scar casts Simba out of his home and wrongfully assumes power at Pride Rock, the audience understands that the movie’s destination will be a fateful reunion between the two. In the meantime, the audience is kept in suspense as they wait to see how Simba – just a cub when banished – will prepare himself in time for the final battle. Similarly, we build suspense in our deliverables by understanding early on the problem facing a community (and the very real, very human consequences of that problem) so that readers can make sense of the information and solutions that come after.

2) Narrativizing deliverables also humanizes project stakes, creating an empathetic connection with the reader. Focusing on the people affected by existing conditions and by projects, chronicling the impact of a place on groups of people over time, and explaining how the interventions proposed by projects can facilitate overall community flourishing are all editorial strategies to emphasize the human dimensions of transportation planning. This in turn can create an empathic understanding within the audience.

Ultimately, our technical writers use narrative techniques to build a report that situates the findings of the project team in the perspective of the audience. A countermeasure isn’t important because it will reduce roadway speeds – it’s important because it will make getting to school or work safer and easier. When viewed this way, technical writing is a service that requires empathy – translating between two audiences – and creates it in audiences, who will be able to understand the needs of their neighbors only if they can first recognize having the need themselves.

Here at Kittelson, we’re building a practice around deliverables that put people first. Reach out to Jennifer Marks, Ian McMurray, or Katie Taylor to discuss any of these ideas or to learn more about Kittelson’s technical writing practice.