July 1, 2024

The City of Fayetteville, North Carolina has experienced a unique development pattern through decades of annexation. While Fayetteville’s population is over 200,000, traditional urban street grids comprise less than seven percent of the city area. The rest is suburban sprawl, created through independently planned developments that are disconnected from one another. In many parts of the City, getting between neighborhoods requires miles of out-of-direction travel on a high-speed, high-volume arterial road, which limits opportunities for walking and bicycling.

Fayetteville’s disconnected layout is particularly concerning during flooding events. The Cape Fear River, which runs along Fayetteville’s eastern border, has swelled on multiple occasions, along with the city’s many creeks that run throughout neighborhoods. This puts neighborhoods that have a single point of access in danger: it’s hard for residents to get out and hard for emergency vehicles to get in.

Recognizing the need for action, the City of Fayetteville incorporated a Connectivity Study into their 2050 Comprehensive Transportation Plan Update. The study kicked off in Summer 2022 with the objective of identifying potential street connections between subdivisions and the arterial network to enhance emergency access and multimodal connectivity. Ultimately, they wanted a prioritized list of improvements that they could take to City Council for funding.

Though Fayetteville faces distinct challenges, connectivity is a real issue in many cities and towns. The City’s initiative to recognize and act on the issue is leading to meaningful progress, and their methodology may be applicable to many other communities. Read on to learn about it!

In big storms, the Cape Fear River and the City's many creeks swell, which in concerning for neighborhoods that only have one point of access.

Where to Begin?

Outside of fire codes, which represent minimum requirements, there is really no guidebook on how to perform a connectivity analysis. The Kittelson team was honored to be brought in to develop a methodology, since the City recognized that Fayetteville’s sprawling layout called for a systematic approach to figure out where time and attention should be focused.

We began by looking at all subdivisions greater than 10 acres in size with just one access point, which was 231 in total. Narrowing further by size (prioritizing the largest subdivisions with the greatest number of households), our list shrunk to 100 for detailed review.

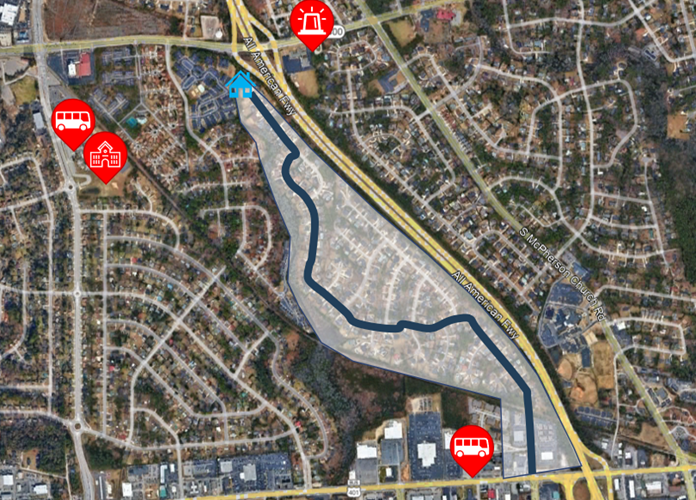

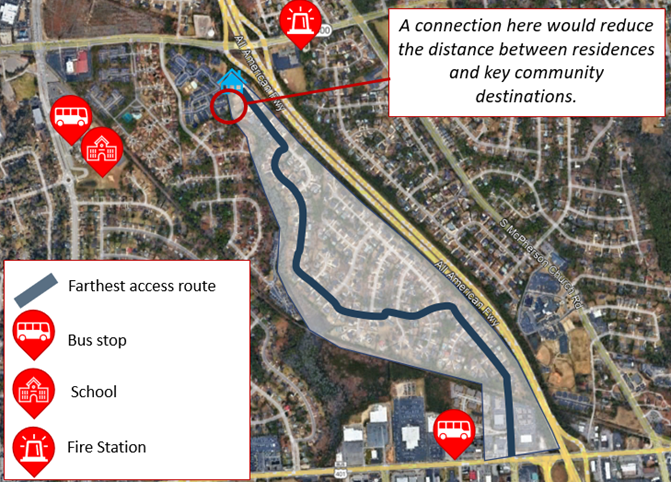

We examined each subdivision, its connectivity challenge, and the maximum distance (house furthest away) from key resources such as bus stops, sidewalks, schools, community centers, fire stations, and arterial/collector roads. Then we mapped out potential connection opportunities for each subdivision and recalculated. For example, if we connect a neighborhood to a nearby apartment complex, what is the new maximum distance to the same resources?

In large subdivisions with only one access point, we measured the maximum distance from key resources.

Then we mapped out potential connection opportunities and recalculated.

For an example, let’s look at the Buckhead subdivision, which has 231 households and a singular access point to the arterial network. The freeway, Buckhead Creek, and a railroad line create barriers between Buckhead and neighboring subdivisions. Nearby bus stops and commercial and community land uses along Cliffdale Road, which runs just north of the neighborhood, are not accessible to the residents in Buckhead. Additionally, while a fire station is physically close, the accessible emergency route to some residences in Buckhead is much longer due to out-of-direction travel.

Providing a connection from the northern point of the subdivision to Cliffdale Road would connect residents to those nearby resources and provide resiliency during emergencies. In fact, it would reduce the furthest distance to the arterial and sidewalk networks each by a mile and the furthest distance to a bus stop by a half mile. It would reduce the furthest distance to a school by over a mile and to commercial land uses by nearly half a mile. Most significantly, a street connection at the northern end of the Buckhead subdivision would decrease the farthest distance from a residence to the fire station by more than two miles, with the potential to greatly reduce emergency response time as a result.

From 175 to 17: Prioritizing the List

This exercise led us to identify 175 possible connections in total. We next needed to find a way to prioritize the projects with greatest potential for impact.

Prioritizing came through assigning each subdivision a score in five different categories: resiliency, equity, feasibility, multimodal access, and community access.

- Resiliency: Looking at the number of households per access point, vulnerabilities of subdivisions based on previous flooding events and floodways of nearby water bodies, and the extent to which the connection improves access to major arterial and collector roads and fire stations.

- Equity: Using the North Carolina Department of Transportation (NCDOT) Transportation Disadvantage Index (TDI) Tool—which estimates a level of disadvantage based on household access to a car, income, mobility impairment, concentration of youth and senior populations, and race—as well as median household income from the U.S. Census Bureau.

- Feasibility: Prioritizing connections that may have a greater chance of implementation due to lower potential cost and constraints.

- Multimodal access: Looking at how connections could reduce the distance between residences and bus stops and existing sidewalks, and create walkability between subdivisions.

- Community access: Looking at how connections reduce the distance between residences and schools, parks, community centers, and commercial uses.

We then worked with the City to weight scores. They expressed a preference to give the most weight to resiliency but still factor in all scores as important performance measures for the goal of the project. Our deliverable to them was a spreadsheet with subdivisions ranked based on this scoring system. They set a threshold that would determine which connections were “high-scoring”.

From there, the City was able to apply more nuanced contextual knowledge to filter out connections due to issues raised by City staff. Police and fire staff also had the chance to look at the results and add their own history, context, and response time information. In general, the City validated the methodology through confirming that subdivisions they knew to be experiencing resiliency challenges were showing up on the short list.

After applying all of these filters, we had a list of 17 new street connections—much more manageable for implementation and cost analysis! We developed an implementation plan that included draft concepts, cost estimates, and cut sheets to take to elected officials and community members to get feedback on placements and types of connections, with the goal to get the improvements incorporated into their city budget. We also looked at development codes, identifying ways to help the City avoid connectivity problems in the future through altering their development ordinance, and built these recommendations into the implementation plan. At their May 2024 work session, City Council approved the Comprehensive Transportation Plan, including the Connectivity Study. This paves the way to identify funding mechanisms for the 17 new street connections, engage with each community to refine the specific connection designs, and incorporate these projects into the City’s Capital Improvement Program.

At their May 2024 work session, Fayetteville City Council approved the Comprehensive Transportation Plan, including the Connectivity Study.

Replicating the Methodology

This was a new process that has the potential to be useful for other communities facing connectivity challenges. As with many transportation issues, it’s a unique blend of systematically processing data while also acknowledging the human side of the issue, letting context and community have a leading voice in the conversation. Once the highest-impact connections are identified, cities can chip away at the solution through getting projects funded and directing the way new developments are built.

We love it when clients come to us with new challenges, and we applaud those that take on initiatives that don’t fit neatly into set scopes of work or planning requirements but are important regardless. In this case, the connectivity study was independent of regularly programmed activities, but the City of Fayetteville found a way to tackle the issue. We’re grateful to have been involved!