November 1, 2024

After World War II, when car usage became more prevalent and it became the norm for people to work downtown but live, shop, and play in the suburbs, many streets were converted from two-way to one-way to facilitate travel in one direction—into downtown in the morning, and out of downtown in the afternoon. Converting two two-way streets to a “pair” of one-way streets was essentially a way to widen the street without making a big change in the cross-section, and was thought to lead to more efficient movement. These decisions resulted in streets with two, three, or four lanes all traveling in the same direction, and they still exist in many cities today.

The question is, did these conversions lead to major improvements in efficiency? While the one-way method may allow for faster vehicle movement in some conditions, the impact is not as significant as you might expect—and more importantly, all other modes, and local businesses, have paid the price. Let’s dive into some of the challenges with one-way streets, as well as the results some cities have seen from converting their streets back to two-way.

Challenges for Pedestrians and Transit Users with One-Way Streets

Multi-lane one-way streets tend to not favor non-auto transportation modes. Here are a few reasons why:

- Safety. A network of one-way streets increases turning movements, which increase the potential for vehicle and pedestrian conflicts.

- Transit. You can’t have bi-directional transit on a one-way street, so you’re left with a split route (inbound and outbound lines on different streets). This can be confusing for infrequent users.

- Conflict Sequences. Many claim that one-way streets are safer for people on foot because they only have to look one way before crossing a street. This is true in some cases, but there’s some fascinating math behind conflict sequences.

Here’s what we mean: for a legal crossing with a pedestrian signal at the signalized intersection of two two-way streets, there are only two possible sequences of vehicle conflicts you will encounter. The first will be a vehicle turning either right or left on green, and the second will be a vehicle turning right on red. As you cross in the other direction, this sequence reverses itself; therefore, as a pedestrian you expect these potential conflicts in one of two sequences.

Here’s what we mean: for a legal crossing with a pedestrian signal at the signalized intersection of two two-way streets, there are only two possible sequences of vehicle conflicts you will encounter. The first will be a vehicle turning either right or left on green, and the second will be a vehicle turning right on red. As you cross in the other direction, this sequence reverses itself; therefore, as a pedestrian you expect these potential conflicts in one of two sequences.

When you combine two one-way streets or a one-way and two-way street (again at pedestrian crossings at signalized intersections), there are now 16 different permutations of the way these conflicts happen—and pedestrians might not know where to look or what to expect. - Pedestrian Visibility. If you have a crosswalk on a multi-lane one-way street, the vehicle closest to the pedestrian may see them, but the vehicle in the next lane may not if the vehicle in front is taller.

- Vehicle Miles Traveled. From a traffic movement standpoint, there is higher VMT in a one-way network because people often have to drive past their destination and recirculate back.

Impact of One-Way Streets on Local Businesses

As many cities have sought to revitalize their downtown areas, a traffic network designed to flush activity out of downtown as quickly as possible at the end of the day is a detriment to downtown businesses. The conversion of multi-lane one-way streets back to two-way is part of a larger trend of making city centers more vibrant and livable; places to live and play, not just work.

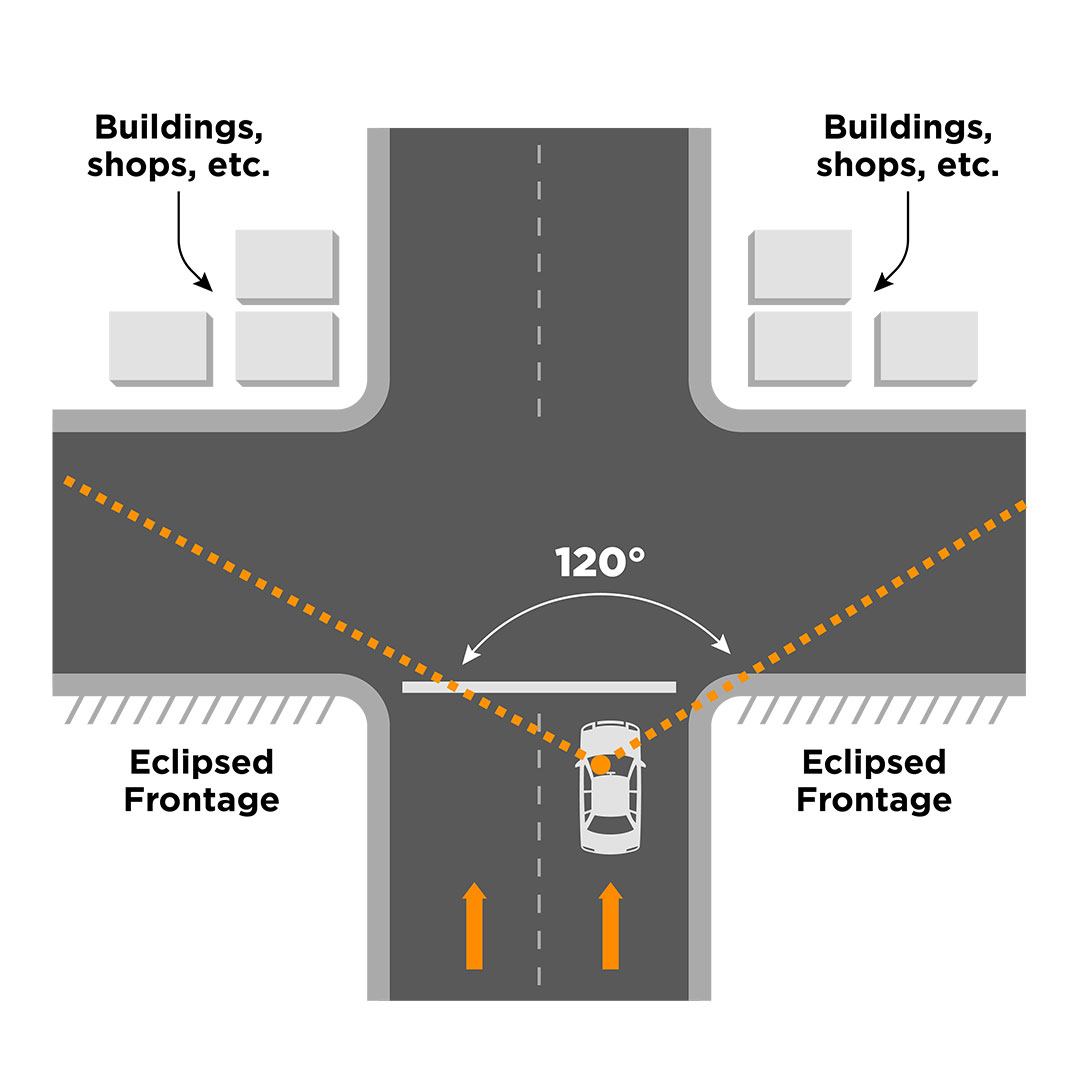

In addition to the conflicting fundamental goals of one-way street networks and city centers today, a specific way that one-way streets have a negative impact on businesses, particularly those that depend on pass-by traffic, is related to storefront exposure. On a one-way street, drivers only see what’s across from them and adjacent to them, so many storefronts are eclipsed (hidden) from view, as shown in this image (original image courtesy of Walter Kulash). On Vine Street in downtown Cincinnati, nearly 40% of businesses closed after it was converted from two-way to one-way traffic.

Impacts of Converting Back to Two-Way: The 20-Year Lookback

In 1999, Senior Principal Engineer Wade Walker wrote a paper for the Transportation Research Board (TRB) titled “Are We Strangling Ourselves on One-Way Networks?” in which he laid out many of the above points and cited examples of cities that were converting back to two-way streets and seeing initial benefits. Recently, he looked at two case studies from the original paper: Lakeland, Florida and downtown Chattanooga, Tennessee. Using Google Earth and Streetview, Wade charted what development had happened since the conversion to two-way, which was more than 20 years ago at the point of his re-examination. Here’s what he saw:

Before the conversion, Wade noted that properties along the stretch in Lakeland that was converted to two-way were sitting about 50% vacant. Today, this corridor is a vibrant shopping and dining street, and downtown housing has been reintroduced.

Lakeland right after the conversion was done, around the year 2000.

Lakeland in 2021.

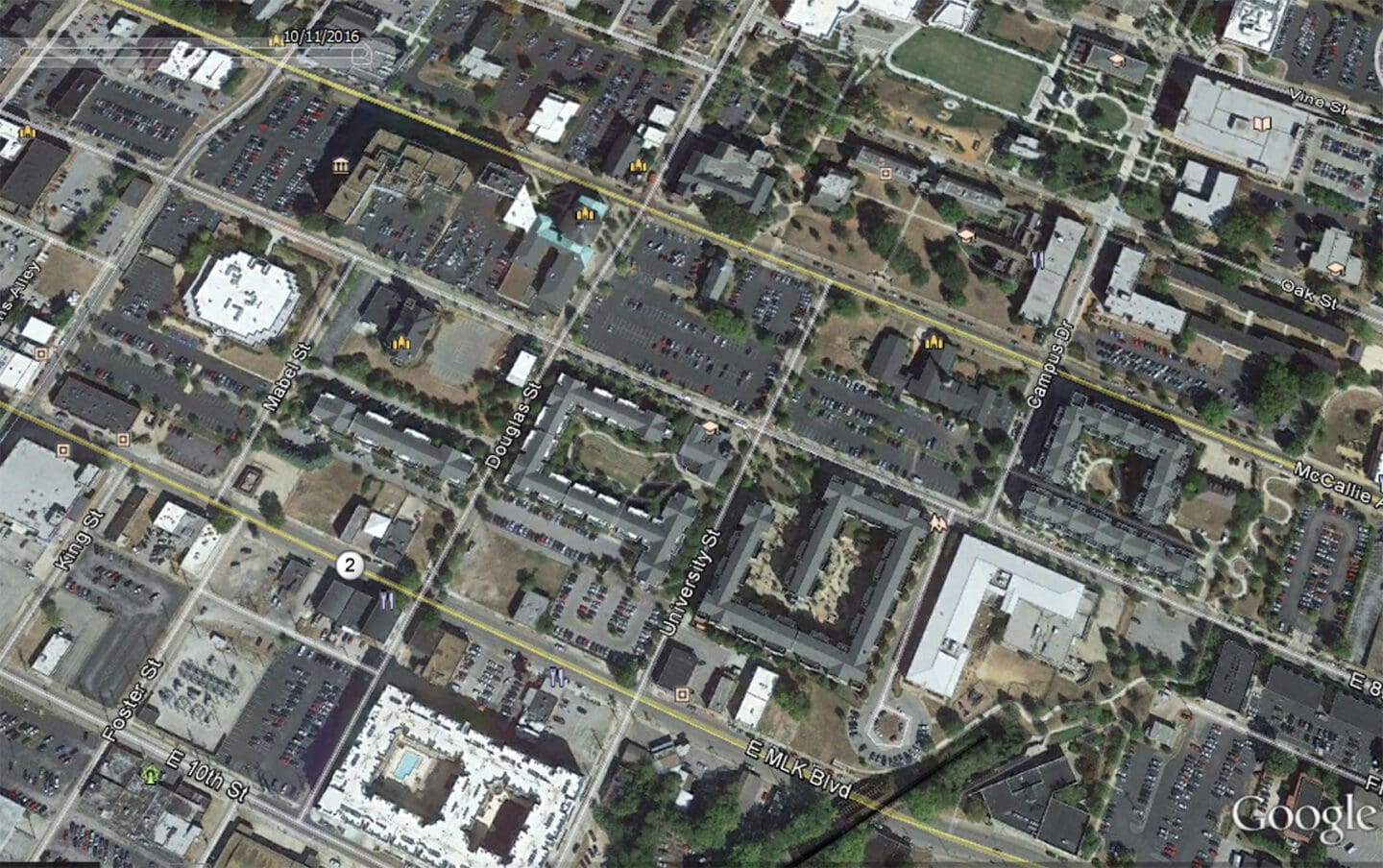

In Chattanooga, where a four-mile one-way pair of streets was converted to two-way, the restoration allowed the University of Chattanooga to extend across the avenue and expand, and encouraged several new developments. It’s also worth noting that the increase in travel time for drivers was less than one minute for a four-mile long corridor.

Aerial view along the one-way pair from 1997. Source: Google Maps.

The aerial view from 2016. Source: Google Maps.

Wade pointed out one more two-way conversion that will be worth checking on in another 20 years. The community of Lynchburg, Virginia spent years getting a two-way conversion across the finish line due to loud opposition from business owners. After the conversion, those business owners are celebrating the change due to the business and life it’s brought back to Main Street.

“Of course, you need to run the traffic studies to understand if the change will work operationally,” says Wade. “However, in the one-way to two-way conversion projects I’ve worked on, the simulation analysis has predicted only seconds of through traffic delay in exchange for these benefits we’re seeing.”

While there is no silver bullet here, if the traffic studies show the change will work operationally, there can be many benefits in a downtown area from converting multi-lane one-way streets back to two-way (how they were likely originally designed).

—

Bust more transportation myths with us! You can also read about: