January 15, 2022

A Native salmon and lamprey fishery for more than 8,000 years, the area surrounding Willamette Falls is rich in history and meaning. Honoring this history was essential to identifying an alignment location for a new bicycle and pedestrian crossing between West Linn and Oregon City, a project that Kittelson recently undertook in support of the Oregon Department of Transportation (ODOT) in partnership with the City of Oregon City, City of West Linn, Clackamas County, and Metro.

Native Presence at Willamette Falls

This project takes place in the traditional homeland of the Clackamas Chinook, whose territory included the Willamette River upstream to the Tualatin River and downstream to about what is now the Port of Portland. Willamette Falls was one of the region’s most productive fisheries, yielding harvests of salmon and lamprey, especially during the spring and summer. The confluence of different cultural groups in the area made the vicinity of the falls an important center of commerce.

Willamette Falls remains a historic property of cultural and religious significance. Even after most surviving Clackamas were removed to the Grand Ronde Reservation in 1856, many Clackamas continued to return to Willamette Falls to fish, maintaining a camp on the west bank into the 1870s. Today, the Grand Ronde, Nez Perce, Siletz, Umatilla, Warm Springs, and Yakama people still visit Willamette Falls to fish.

Willamette Falls remains a historic property of cultural and religious significance. Even after most surviving Clackamas were removed to the Grand Ronde Reservation in 1856, many Clackamas continued to return to Willamette Falls to fish, maintaining a camp on the west bank into the 1870s. Today, the Grand Ronde, Nez Perce, Siletz, Umatilla, Warm Springs, and Yakama people still visit Willamette Falls to fish.

The Need for an Additional River Crossing

The history of the study area provides a crucial backdrop to the 2021 effort to add another crossing to this section of the Willamette River, which is now lined by Oregon City on one side and West Linn on the other. Oregon City and West Linn are connected by the Historic Arch Bridge (OR 43).

Listed on the National Register of Historic Places, the 745-foot Arch Bridge is an iconic community symbol. However, as with most river crossings constructed in the 1920s, the Arch Bridge was not designed for people walking and biking. Its lack of ADA-compliant bike facilities and sidewalks makes navigating the bridge extremely stressful for those confident enough to traverse it and inaccessible for those who rely on mobility devices. Due to the historic nature of the bridge and its structural design, it cannot be widened to accommodate separated bicycle facilities or sidewalks that comply with ADA standards and support people with limited mobility. The closest crossings of the Willamette River from this location are the Sellwood Bridge and the Canby Ferry, each more than eight miles away – which is too far for people to realistically travel between Oregon City and West Linn by walking, biking, or rolling.

The quest to provide a safer way for people walking and biking across the Willamette River became Oregon’s first project to apply the Social Equity Framework outlined in the Oregon Department of Transportation’s Strategic Action Plan.

Prioritizing Equity in ODOT’s Strategic Action Plan

ODOT’s Strategic Action Plan is a roadmap built around three priorities: a modern transportation system, sufficient and reliable funding, and equity. It was released right before the West Linn/Oregon City Pedestrian and Bicycle Bridge Project kicked off, giving this project an opportunity to apply the pieces of its social equity engagement toolkit. It is ODOT’s goal that by the end of 2023, all ODOT projects will apply these tools in their community engagement efforts.

Applying the Social Equity Framework to a Ped/Bike River Crossing

The goal of the project was clear: identify an alignment for a safer, more comfortable Willamette River crossing for people walking, biking, and rolling. However, we needed to thoughtfully engage the communities in and around West Linn and Oregon City to determine the approach. Recognizing Willamette Falls’ rich history and significance of place, ODOT sought to actively solicit the voices of Tribes in their decision-making, and backed the commitment with significant funding dedicated to community engagement.

To do this, we partnered with We All Rise, a Portland-based consulting firm that works to uplift input of historically marginalized and underserved stakeholders in community development projects. The engagement was tremendous, including more than 750 responses to a public survey that was distributed in multiple languages along with focus groups, open houses, and walking tours. The project team provided reimbursement gift cards in exchange for time in focus groups with individuals experiencing low income. We had a project advisory committee that brought together a broad set of community perspectives, including tribal representatives from six Tribes, interested government parties, and representatives of different community groups. We held discussions with additional entities that have a stake in the river crossing, including surrounding businesses, emergency service providers, schools, and historical societies. For residents with a high chance of being impacted by potential crossing locations, we went door to door to share information and collect feedback.

What We Learned

From all this engagement, we heard that almost 80% of respondents believe a bridge dedicated to people walking, biking, and rolling would benefit the community, though they had varied input on where they prefer the bridge to go. We received mixed feedback from the Tribes: some did not support a bridge closer to the Willamette Falls because they do not want to increase general public access and views of the culturally significant sites within the area. Other Tribes saw the potential economic and historical awareness benefits of providing a community connection in the vicinity of the culturally significant area.

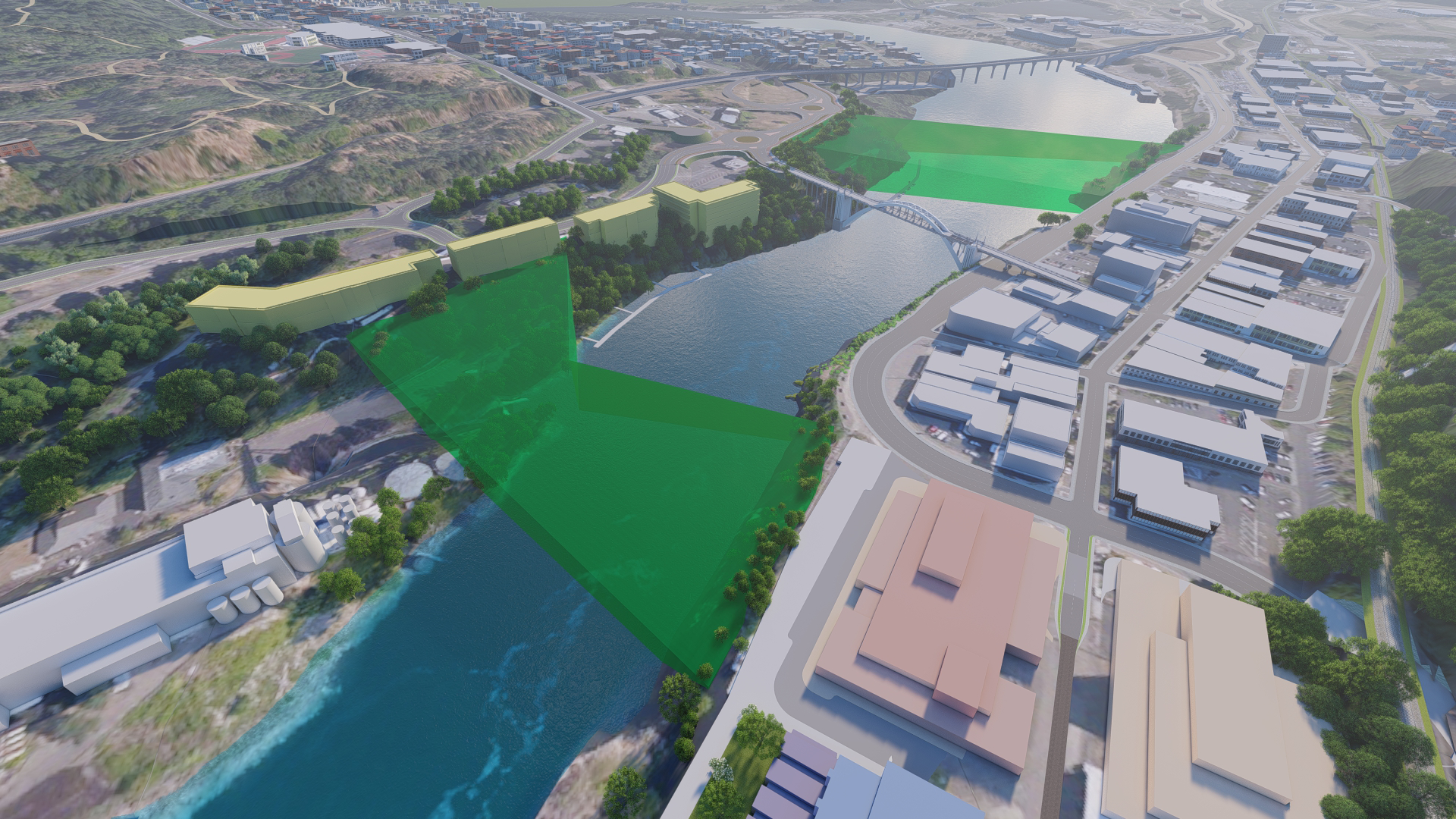

The project team developed a list of seven initial bridge alignments and expanded the alignment options to 15 based on feedback. We then used evaluation criteria to determine the most promising alignments based on how well they would support community needs and provide positive experiences for people traveling on foot, by bike, or using other mobility devices. View a visualization of the initial seven alignments here, created by Visual Communication Specialist Steve Rhyne:

So, Where Will People Walking and Biking Cross the Willamette River?

Based on this evaluation, two corridors emerged as the preferred options: a downstream corridor and upstream corridor. Why corridors and not specific alignments? For one thing, it was clear more input was needed from our most important stakeholder group: local Tribes. Engagements to this point had given us a range of feedback from Tribes regarding placement, and we didn’t have enough information to zero in on the bridge location just yet. A secondary reason was the number of major upcoming developments and planned transportation projects. Waiting to pick the final alignment will keep options open as more of these projects are finalized and constructed.

The proposed corridors, along with a high level cost estimate for each and an analysis of benefits and burdens, are summarized in a concept plan available on ODOT’s website. The plan outlines steps to implementation, starting with a recommendation for Oregon City and West Linn to adopt the corridors and a crossing alignment refinement study into their Transportation System Plans (TSPs). Subsequent steps include more partner agency coordination, additional studies of cultural and environmental resources, and additional Tribal engagement efforts before identifying a preferred alignment. The plan also identifies 11 potential funding sources for design and construction to bring the bridge to reality.

ODOT’s Continuing Commitment to Equity

An equity approach has been fundamental to this project, from the investment in community outreach to the choice to not rush to select an alignment when more information is needed. ODOT is continuing to build out the social equity engagement toolkit and apply it to projects across Oregon, and sharing progress on their website.