October 14, 2020

As transportation professionals, we are in the public health business. The transportation policies, plans, projects, and recommendations we develop have an impact on the health of our communities and the activity levels of our residents.

It’s important we embrace this responsibility and understand the strong connection between transportation and health. By shifting our transportation lens from moving cars to encouraging and making it possible for people to safely, efficiently, and comfortably walk, bike, and and move, we can help mitigate grater public health concerns.

There are numerous opportunities from policy planning to project implementation where health can be integrated and even take a front seat in the decision-making process. This includes institutionalizing health outcomes into policies, using health data and outcomes to inform our project programming and design, and monitoring the impact of our projects on the health of a community.

Here are six practical ways we can do that.

1. Create Equitable Access

Are we creating equitable access to healthy living through the transportation decisions we make?

Vulnerable population groups, including people with mobility limitations, limited incomes, and the elderly, are more likely to lack travel options and therefore, may have limited access to jobs, health care, social interaction, and healthy food.

Health data provides an insightful picture of current health conditions, trends, and disparities. This information can help inform planners and community leaders on the best infrastructure needs and solutions and can allow them to track how changes to the built environment are helping or harming their communities. In Phoenix, where I live and work, we have created socioeconomic and health equity models to map out areas with higher concentrations of individuals with health issues and understand the correlation with socioeconomic status. The models allow transportation planners to quickly visualize areas where vulnerable population have high disparities in access to quality pedestrian and bicycle facilities.

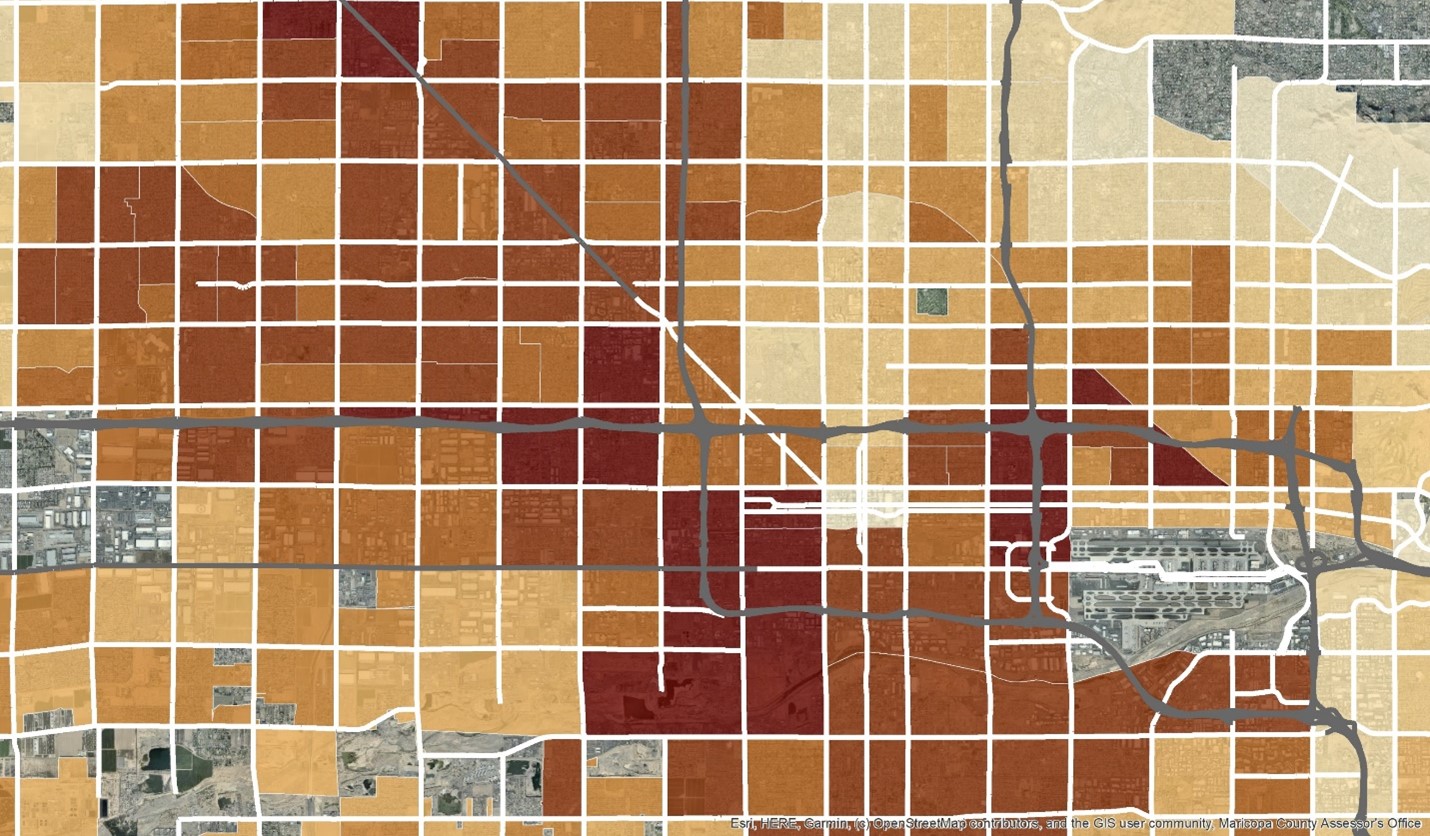

Here’s an example. Areas illustrated in a darker shade on the map below have higher rates of chronic public health conditions, such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes.

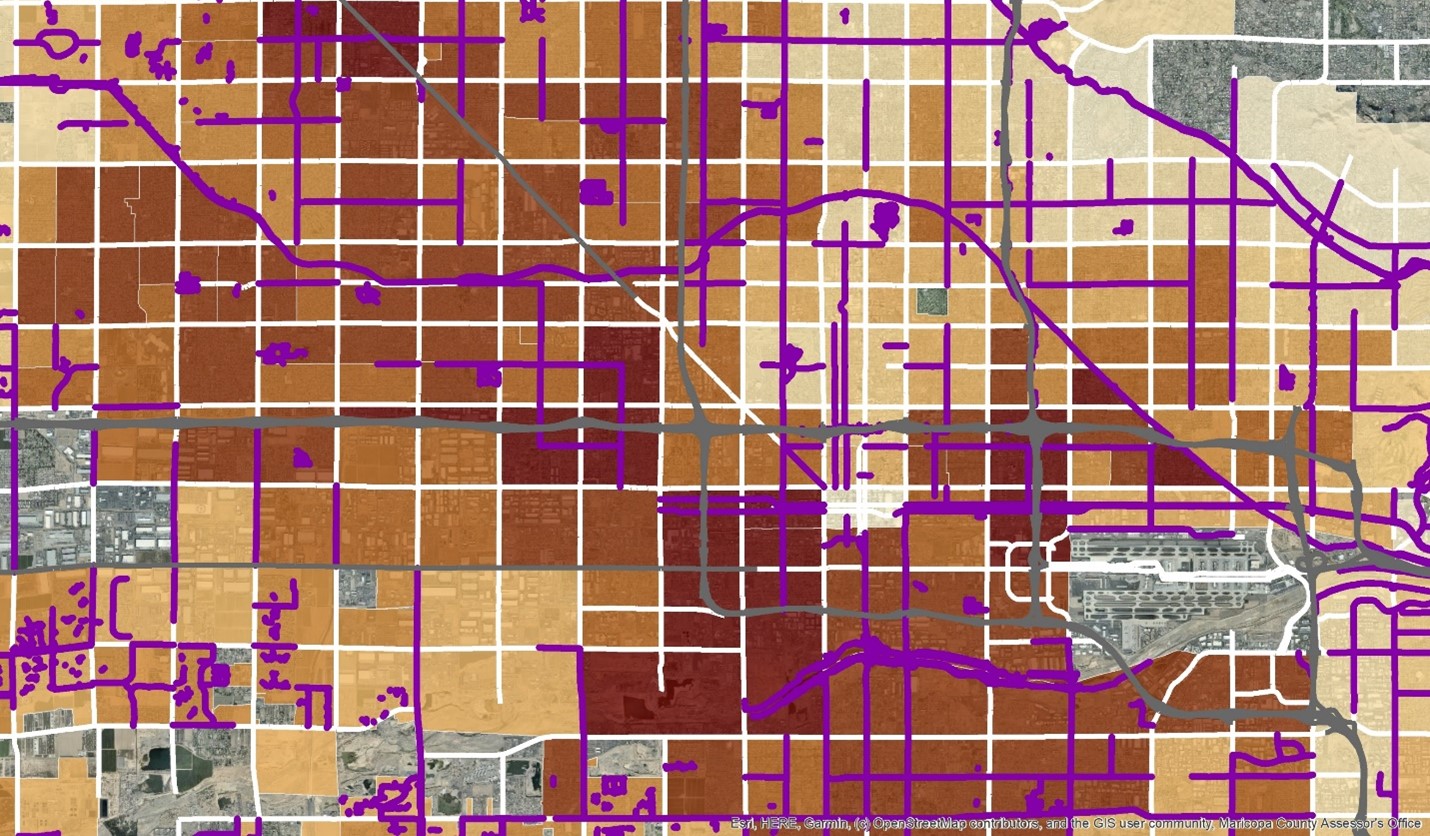

To understand how our transportation system impacts our health, we can overlay our current bicycle network onto this health equity model. In this map, the purple areas represent current bike lanes and shared use paths. Now, you can really start to see areas of concerns that have significant disparities in access to bike facilities. But there are also areas of concerns that do have bicycle facilities. This model serves as a valuable tool to understand how the types of infrastructure we build help contribute or deter physical activity.

If we dig deeper, we can start to see differences in the quality of bicycle facilities. The photo illustrated on the below on the left is in an area in lower chronic health concerns and higher socioeconomics. This type of facility is an attractive and wide, people-focused shared use path that is somewhere you would want to be and go on a walk. For me, this type of facility gives me an instant sense of comfort and safety.

In comparison, the image on the right is located in an area with higher health concerns and lower socioeconomics. As the photo illustrates, there is one narrow bike lane where people biking are right up against vehicles driving. This illustrates very different sense of safety and comfort than the image on the left. And this is in a disadvantaged socioeconomic area where people have to walk or bike. We, as transportation professionals, need to be aware that decisions that we make not only influence the use of a facility but also a person’s safety.

Creating maps and models like these makes it difficult to ignore the correlation between access to safe, high-quality active transportation facilities and better health outcomes.

2. Remove Active Living Barriers

Another key component of creating equitable access is removing barriers that may limit a person’s desire or ability to walk, bike or move. These could be physical barriers, such as a lack of facilities, or perceived barriers, such as feeling unsafe because there is limited lighting along a path.

A lack of connectivity in our streets also creates barriers to physical activity. In the example above, the housing community is adjacent to an amazing park and aquatic center. But for those living in the neighborhood highlighted, there is a large wall limiting their access. Instead of a quick walk across the road, they must walk nearly a mile to get to the park. So just imagine a day when you want to go for a walk, but just putting on your shoes to leave feels like a chore. Now tack on an additional mile of walking, and the chances you make it to the park just got a lot lower.

3. Context-Sensitive Designs

In addition to being connected, streets need to be designed to the unique needs of their users and the land use needs of the corridor. Context-sensitive designs move away from vehicle-focused designs to incorporate the human experience. They are solutions that provide multimodal connectivity within the context of the aesthetic, social, economic, and environmental needs of a community – creating spaces that people want to be.

In addition to being connected, streets need to be designed to the unique needs of their users and the land use needs of the corridor. Context-sensitive designs move away from vehicle-focused designs to incorporate the human experience. They are solutions that provide multimodal connectivity within the context of the aesthetic, social, economic, and environmental needs of a community – creating spaces that people want to be.

4. Improve Safety For All Users

Another critical aspect of promoting active living through transportation is making our transportation facilities as safe as possible.

This includes creating the perception of safety. How safe someone feels walking, biking, or using transit is critical to whether they choose to use that mode of transportation. Understanding the unique needs of our users is critical to designing a transportation system that people will use. For instance, a confident bicyclist may not be scared to ride on the shoulder of a rural highway, whereas families with children (or honestly myself) will look for bicycle facilities that provide extra protection, safety, and comfort.

It is also important to look at safety from an equity standpoint. Historically, many underserved populations have been ignored during the transportation planning process – leading to unsafe conditions and a high rate of crashes in communities of concern. It’s important to remember that often those who walk or bike in unsafe conditions do so because maybe they cannot drive or afford a vehicle. Identifying high crash areas with a high number of disadvantage population groups is a step toward determining what facility design and improvements are needed to provide all of our residents with safe modes of travel.

5. Expand the Transportation System

What do we consider to be a transportation corridor? If we only think roads, we need to rethink the definition.

What do we consider to be a transportation corridor? If we only think roads, we need to rethink the definition.

By integrating trails and sidewalks into our transportation system, we can create comfortable, people-focused spaces that encourage and entice physical activity. The Atlanta BeltLine, pictured left, is a prime example of how Atlanta converted an old rail line into an amazing public space that is now often full of residents walking, biking, and just enjoying their community. It is a true example of “if you build it, they will come.”

The CDC recommends adults engage in 30 minutes of daily physical activity. When neighborhoods, trails, and street design make walking and biking easy to do, this 30-minute recommendation becomes part of a person’s normal everyday activities.

6. Make Health a Priority

To bring all of these strategies together, we have to make health a priority and institutionalize and integrate health into our policies, programs, and plans.

Maricopa County DOT (MCDOT) in Arizona has taken their role as shaping the county’s health seriously. They integrated health objectives and goals into their planning process. And they didn’t stop there.

MCDOT has been at the forefront of using the project prioritization process to advance its health and quality of life objectives. MCDOT developed a prioritization process that evaluates projects against established performance measures. The MCDOT Active Transportation Plan, and now their 2045 Transportation System Plan, assigns points to each project, giving more weight to projects that improve safety, provide high-quality multimodal options, and are within areas with high social or health inequity.

Making It Happen: Build a Business Case

At the end of the day, to make these six strategies a reality, we need to build a business case to decision-makers that quantifies the health, economic, safety, and quality of life benefits for integrating and improving health in transportation. Achieving buy-in from community members, and ultimately attaining political support, helps us continue implementing and funding all the strategies I’ve laid out here.

It’s also important to include public health agencies, social service organizations, and private health foundations as equitable partners through the planning and design process. Asking public agencies to review draft reports is too late to build a strong collaboration.

In Arizona, our local public health agency has worked closely on several of our plans and have truly served as champions for the community. They’ve helped to conduct one-on-one outreach at underserved areas or at social service providers, such as the Women, Infant, Children Clinic, and they’ve helped to create grassroot campaigns to that created excitement and enthusiasm in low-income neighborhoods to walk and bike to their local park so they can get their steps in.

I’ve been lucky enough to work with local public health officials that have truly helped develop grassroot campaigns to change the way our communities. In Phoenix, public health agencies have assisted in conducting specialized outreach in underserved communities at the social service agencies (such as the Women, Infant, Children clinics) so we can hear directly from those that don’t traditionally participate in the planning process. Our public health agencies have also help develop grassroot campaigns to create a ParkRX program that generated excitement and enthusiasm in low-income neighborhoods to walk and bike to their local park so they can get their steps in.

Health Impact Assessments (HIAs)

Health impact assessments are one way to bring health evidence to decisions and to build that business case to your community members and decision-makers. An HIA is a six-step process that helps communities and decision-makers collaborate to identify the health needs of an area, evaluate how improvements make impact the health of the community, and develop recommendations that can help maximize health benefits and minimize preventable risks, such as chronic disease and injuries.

Continue the Conversation

How are we creating healthier communities through our work in transportation? I’m always open to a good discussion on this topic, and welcome you to contact me if you’d like to talk more about any of the strategies I’ve shared here.