October 21, 2024

Spooky season is officially upon us! To embrace the reason for the season, we watched five transportation-centric frightening flicks (one for each mode: driving, walking, biking, rail, and transit) to understand what they tell us about our own anxieties about travel, mobility, and being human. So summon your bravest friends, make some popcorn (we like ours mixed with Milk Duds), and hunker down on that living room sofa.

A warning: In this article, spoilers abound. If you’re hoping to avoid them, we’d recommend stopping here, watching the movies (they’re fun!), and then returning for the discussion. Or skim through the headings and linked trailers to get a taste. Either way, continue at your own peril!

Illustration by: Emily Lewis, Senior Graphic Designer

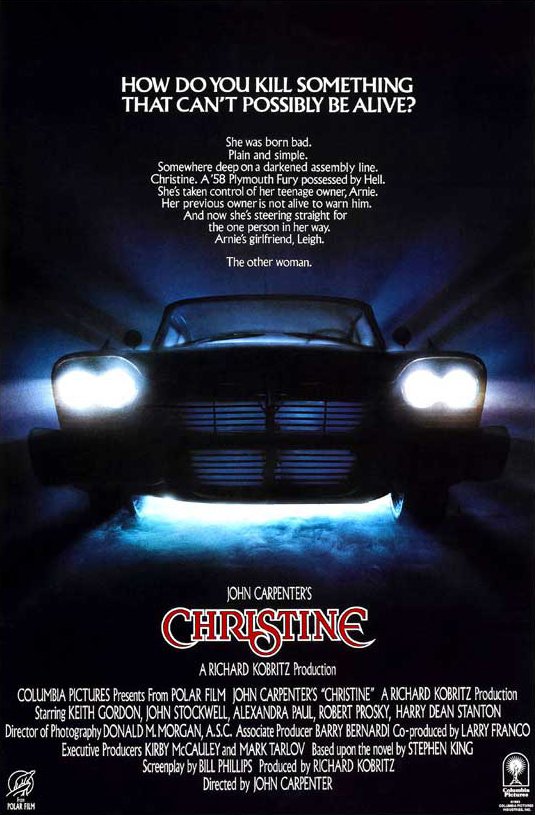

For people who love (or hate) cars: Christine (1983)

John Carpenter’s Christine, adapted from the Stephen King novel, depicts transportation as a corrupting social element. Set in the 1980s, the movie follows teen dweeb Arnie (played by Keith Gordon) as he falls hard for his cherry red 1950s Plymouth Fury, Christine, a vampiric force who incrementally draws Arnie away from his family, friends, and college and toward the anarchy of serial hit-and-run, eternal youth, and vintage red jackets.

Arnie’s red windbreaker—a nod to the iconic jacket in Rebel Without a Cause—is a surprisingly important clue to understanding the film’s core fear, which draws on two postwar American moral panics: the advent of rock and roll and the popularization of the automobile. At the time, many Americans believed that these cultural shifts would have deleterious effect on youth, offering them an unsupervised mobility that would, no doubt, lead to delinquency and depravity. The film is replete with references to the 1950s. Christine communicates through her radio, which inexplicably plays snippets of rock and roll by artists like Little Richard and Ritchie Valens. Arnie and his human girlfriend take the newly restored Fury to the drive in, where Christine swiftly tries to dispatch her competition.

On the surface, Arnie’s descent into obsession and madness feels like a reviving of the 1950s moral panics, an admission that automobiles indeed threaten the nation’s youth and morality. Yet the film ultimately maintains an ambivalent disposition toward Arnie’s fall from grace: while the narrative action indulges the misplaced anxieties of these moral panics, the movie never fully endorses adulthood on the straight and narrow, either. (Arnie’s parents are dull, his human girlfriend is boring.) One emerges from the film thinking that, if Arnie’s love for Christine was ultimately destructive, it wasn’t exactly unfounded given the blandness on offer everywhere else.

We are even made to feel ambivalent about Christine herself. In our favorite sequence, Christine, lit only by her headlights and the flames billowing from her frame, chases down the bully responsible for what he intended to be her destruction while 80s keyboard titters in the background. As viewers, we are both the predator and the prey as our perspective shifts between license-plate level and staring down her headlights. At license plate level, we aren’t just driving the car, we are the car.

In the end, Christine capitalizes on the anxiety that the individual freedom offered by automobiles will unlock our subversions and eject us from society and perhaps embodies the fear that Americans have chosen the automobile over community, stability, and our own sanity.

Movie Poster: “Christine.” IMDb. Accessed October 22, 2024. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0085333/mediaviewer/rm4278980608/.

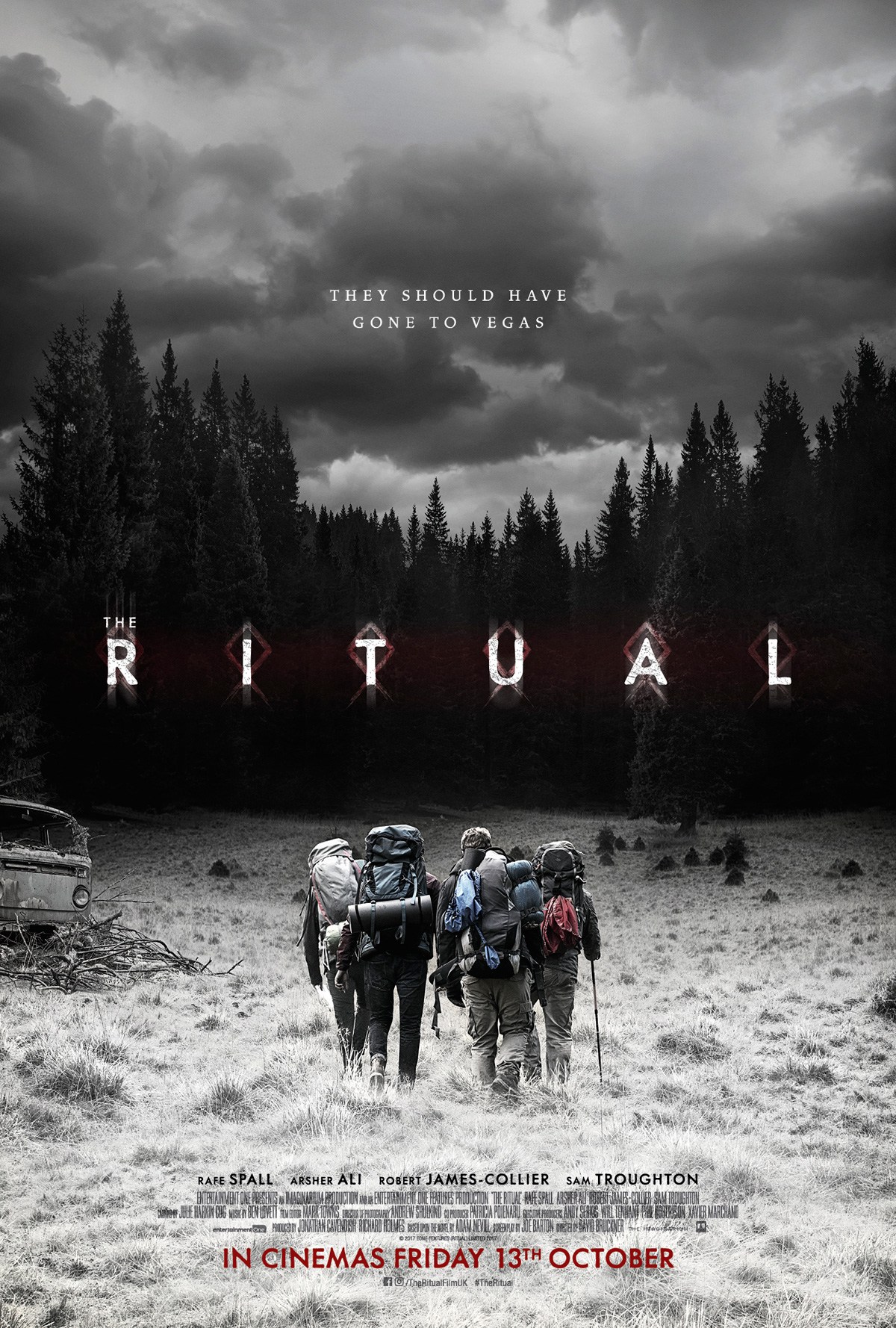

For outdoor enthusiasts and people who like a big walk: The Ritual (2017)

The Ritual, a Netflix movie about four men who hike in (haunted!) Scandinavian woods to commemorate their deceased friend, is preoccupied with multiple kinds of danger faced by those who travel on foot.

The Ritual, a Netflix movie about four men who hike in (haunted!) Scandinavian woods to commemorate their deceased friend, is preoccupied with multiple kinds of danger faced by those who travel on foot.

The movie observes the way a long walk in nature can act as a funhouse mirror on human agency, alternately contracting and dilating our centrality within the world we inhabit. A long hike can boost one’s sense of exceptionalism—we prove to ourselves that we can withstand nature’s elements with human ingenuity and temerity—as well as one’s sense of fragility, as the isolation of the activity exposes us to threats both external and, perhaps more surprisingly, internal.

In many ways, the film is about the vulnerability of people traveling by their own two feet, both in the city, where a friend is killed as a bystander during a convenience store robbery, and in the forest, where our protagonists are hunted by an otherworldly creature. As the friends are picked off as interchangeable sacrifices, the group frays in the face of nature’s ambiguities—whether to take a “shortcut” (always no), whether the group is lost (absolutely), whether to sleep in a dilapidated timbered cottage in the woods (hard pass)—and by their shared personal trauma. Blamed both for the instigating city death by his surviving friends and “marked” by the creature to join its cult of worshippers, our main character (played by Rafe Spall) must battle his way, barefoot at the end, through a truly frightening forest.

Much of the tension in the film comes from the environments through which our cohort must trek: a wind-whipped ochre plain; an endless sea of evergreens with piercing lower branches; and a dense copse of unsettlingly thin trees. Environs in the film are unstable, particularly when a creature-induced hallucination brings a florescent-lit convenience store to the middle of a mossy forest floor. Suffice to say that the pedestrians in this film feel neither safe nor comfortable.

Movie Poster: “The Ritual.” IMDb, February 9, 2018. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt5638642/?ref_=tt_mv_close.

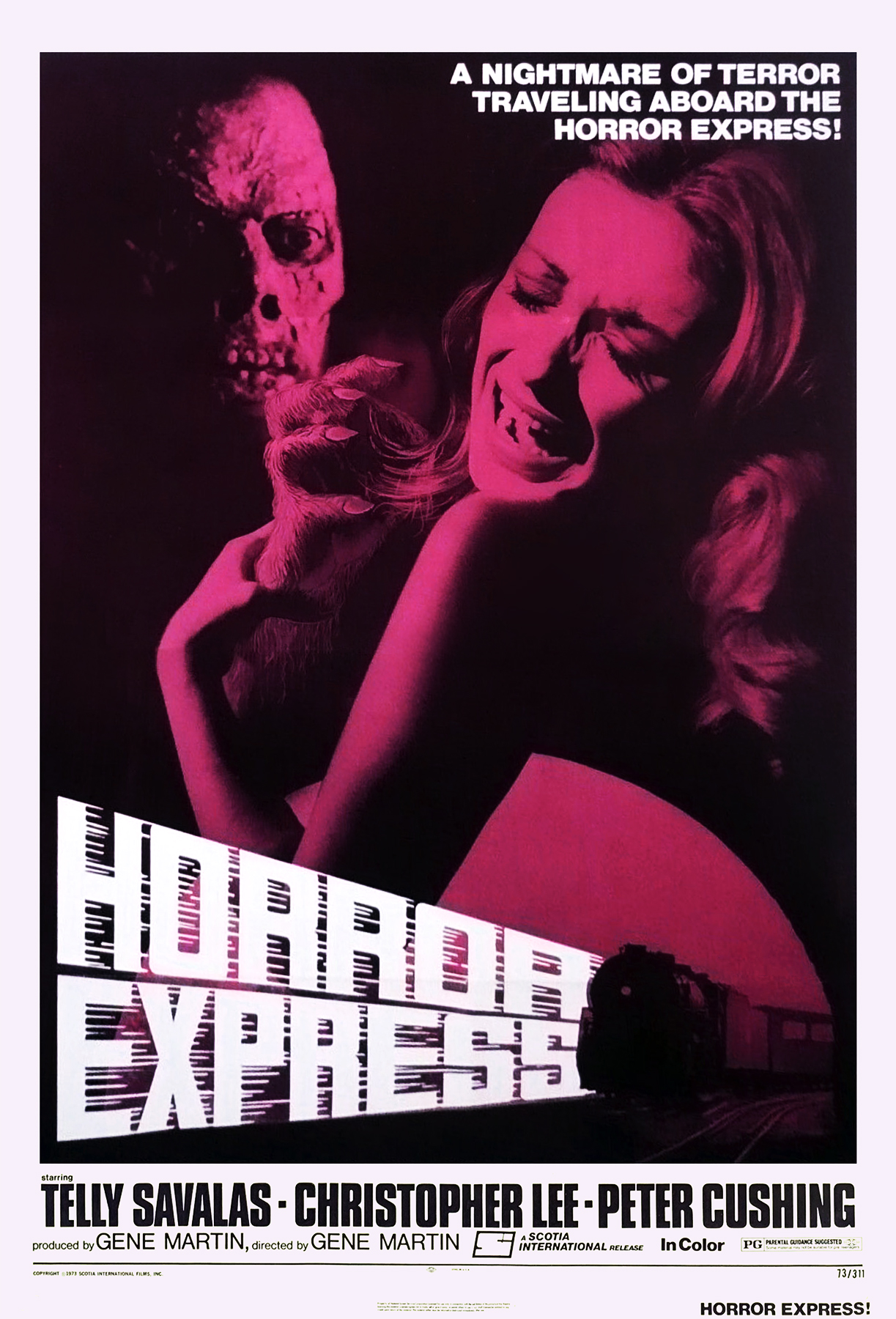

For railfans, especially railfans who appreciate practical effects: Horror Express (1972)

At the center of Horror Express is a conflict between science and faith. Set in 1906, the story follows a loose coterie of Western scientists who get more than they bargained for when one of their numbers, Professor Alexander Saxton (Christopher Lee), smuggles a prehistoric hominid specimen aboard the transcontinental train journey from Manchuria to Moscow. Sometimes friends and sometimes rivals, these academics spy and scheme for possession of Saxton’s specimen until—accidentally and inevitably—they awaken it and set its fury loose upon the train. Rounding out this drama is a pious contessa accompanied on her travels by a Rasputin-like creep, Father Pujardov (Alberto de Mendoza), who at first abhors the creature as satanic before eventually becoming its biggest fan.

At the center of Horror Express is a conflict between science and faith. Set in 1906, the story follows a loose coterie of Western scientists who get more than they bargained for when one of their numbers, Professor Alexander Saxton (Christopher Lee), smuggles a prehistoric hominid specimen aboard the transcontinental train journey from Manchuria to Moscow. Sometimes friends and sometimes rivals, these academics spy and scheme for possession of Saxton’s specimen until—accidentally and inevitably—they awaken it and set its fury loose upon the train. Rounding out this drama is a pious contessa accompanied on her travels by a Rasputin-like creep, Father Pujardov (Alberto de Mendoza), who at first abhors the creature as satanic before eventually becoming its biggest fan.

What’s the big deal about this creature, anyway? Saxton is convinced this prehistoric creature holds the secret to confirming “the theory of evolution” and determining “the origin of man,” though the train’s resident Contessa decries evolution as “immoral.” The movie seems to agree: as it bores its red diode eyes into its victims, the creature steals passengers’ memories and skills, transcribing everything it witnesses into its very cells. The creature represents not only a link in the sequence of human evolution but also the concept of evolution in action, advancing and changing at the expense of those around it. The movie ultimately deems the scientist’s insistence that further scientific innovation will demystify and subjugate all of the universe’s as hubristic: when the creature eventually inhabits Father Pujardov, the representatives of science and faith merge, effectively equating our rabid appetite for innovation and progress with religious fanaticism.

And then there’s the choice to set this action aboard a locomotive, which at first glance can appear mostly a decision of convenience. As setting, the train splits the difference between the decorative and the functionary—it provides fetching mise en scene while enclosing the characters, making them easy targets for our monster to pick off one by one—but it might initially appear to contribute little to the film’s central investigation into the perils of progress.

At second glance, however, the locomotive becomes a symbolic summation of the movie’s fear of progress, acting as a tidy representation of the dangers of unstoppable forward movement. Interior action sequences are intercut with visions of the train careening across the screen faster and faster, the sound of its churning wheels growing more frantic with each major plot development. Filmed near the end of the space race but set in the early nineteenth century, Horror Express swaps rocket for train to contend with contemporary fears at humanity’s insatiable intent to explore space in pursuit of progress and scientific knowledge. Ultimately, the scientists only manage to save themselves by sequestering themselves at the back of the train and detaching their car from the locomotive, sending it—and the monster—careening over a cliff. In other words, man’s thirst for scientific and technological innovation leads directly to ruin; the only way to save ourselves is to surrender our interest in Pandora’s cargo.

This film is a delight of practical effects (and our favorite of the five we screened for this article). Viewers can look forward to a deliciously squeam-inducing autopsy, a hair and makeup approach that hilariously mixes 1970s and early 1900s fashion, and a clearly miniature train that clicks faster and faster along a miniature track toward its ultimate demise.

Movie Poster: “Horror Express.” IMDb, January 3, 1974. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0068713/?ref_=nv_sr_srsg_0_tt_8_nm_0_in_0_q_horror%2520express.

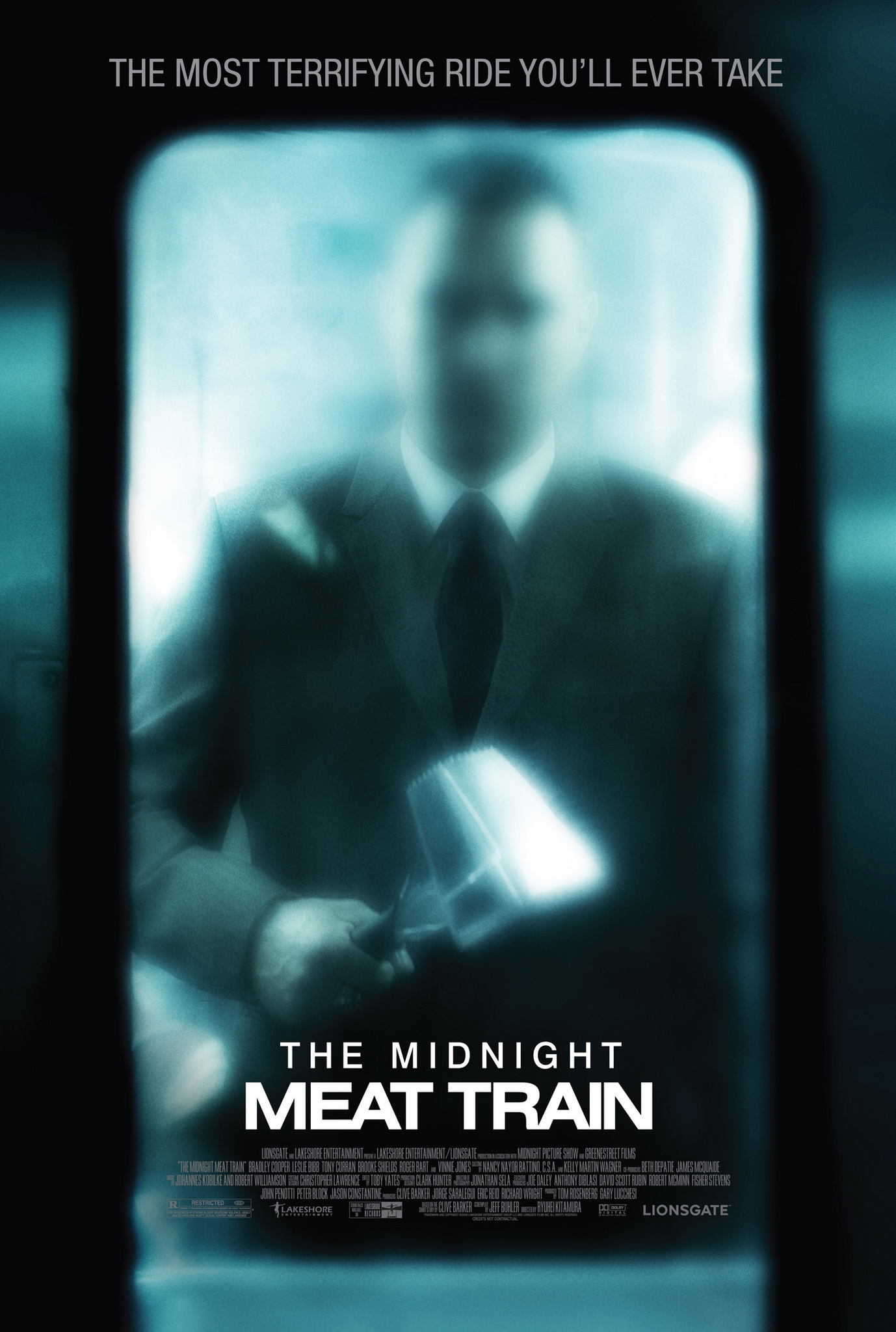

For fans of gore (and not the kind at the end of an entrance ramp): The Midnight Meat Train (2008)

Based on a Clive Barker short story, the 2008 film The Midnight Meat Train is a gratuitous, silly title we can’t in good faith recommend except to the most diehard fans of gore and/or Bradley Cooper. Cooper plays Leon, a small-time photographer who, looking for his big break, descends into the underbelly of an unnamed City’s subway to shoot “the real city”—which, according to his girlfriend, has “always been hell.” After a series of sleepless nights, Leon develops a voyeuristic fascination with a man he suspects is murdering individuals on the subway. This man, who is indeed murdering people on the subway (and how! His weapon of choice is a meat tenderizer), is revealed in the final act to be a Lovecraftian municipal employee, a goth civil servant who harvests the meat of the passenger class to feed and appease a horde of demons living at the subway’s last stop. (Because the City is hell, get it?)

Based on a Clive Barker short story, the 2008 film The Midnight Meat Train is a gratuitous, silly title we can’t in good faith recommend except to the most diehard fans of gore and/or Bradley Cooper. Cooper plays Leon, a small-time photographer who, looking for his big break, descends into the underbelly of an unnamed City’s subway to shoot “the real city”—which, according to his girlfriend, has “always been hell.” After a series of sleepless nights, Leon develops a voyeuristic fascination with a man he suspects is murdering individuals on the subway. This man, who is indeed murdering people on the subway (and how! His weapon of choice is a meat tenderizer), is revealed in the final act to be a Lovecraftian municipal employee, a goth civil servant who harvests the meat of the passenger class to feed and appease a horde of demons living at the subway’s last stop. (Because the City is hell, get it?)

This movie first literalizes a longstanding, generalized, and largely unfounded fear that urban mass transit systems pose a serious safety risk to users before then doubling down on this position, arguing that the point of mass transit is to create a civic permission structure for violence that, if regrettable, is essential to the city’s continued operation. It’s an acknowledgment that mass transit functions as a circulatory system in large cities like New York and London, shepherding its lifeblood (the residents) from here to there, but a cynical one, in that it ultimately suggests that the system uses us more than we use it.

Viewers who subject themselves to this early aughts time capsule can look forward to 1 hour and 40 minutes of blue light and soft, unfocused edges. (For millennials, the whole film will feel like the photo journalism senior project from your hipster friend in high school.) Although we must admit, Bradley Cooper’s thin fashion scarf helps offset the films innumerable plot holes and its “wait, what?” ending.

In the end, this movie is stupid, shlocky fun, but the way it portrays users of mass transit—as suckers, sheeple, or predators instead of as people of thrift, community, or simple carelessness—is only regrettable. It reflects the classism that powered the rise of auto-centrism in midcentury American consumerism and urban design.

Movie Poster: “The Midnight Meat Train.” IMDb, October 31, 2008. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0805570/?ref_=fn_al_tt_1.

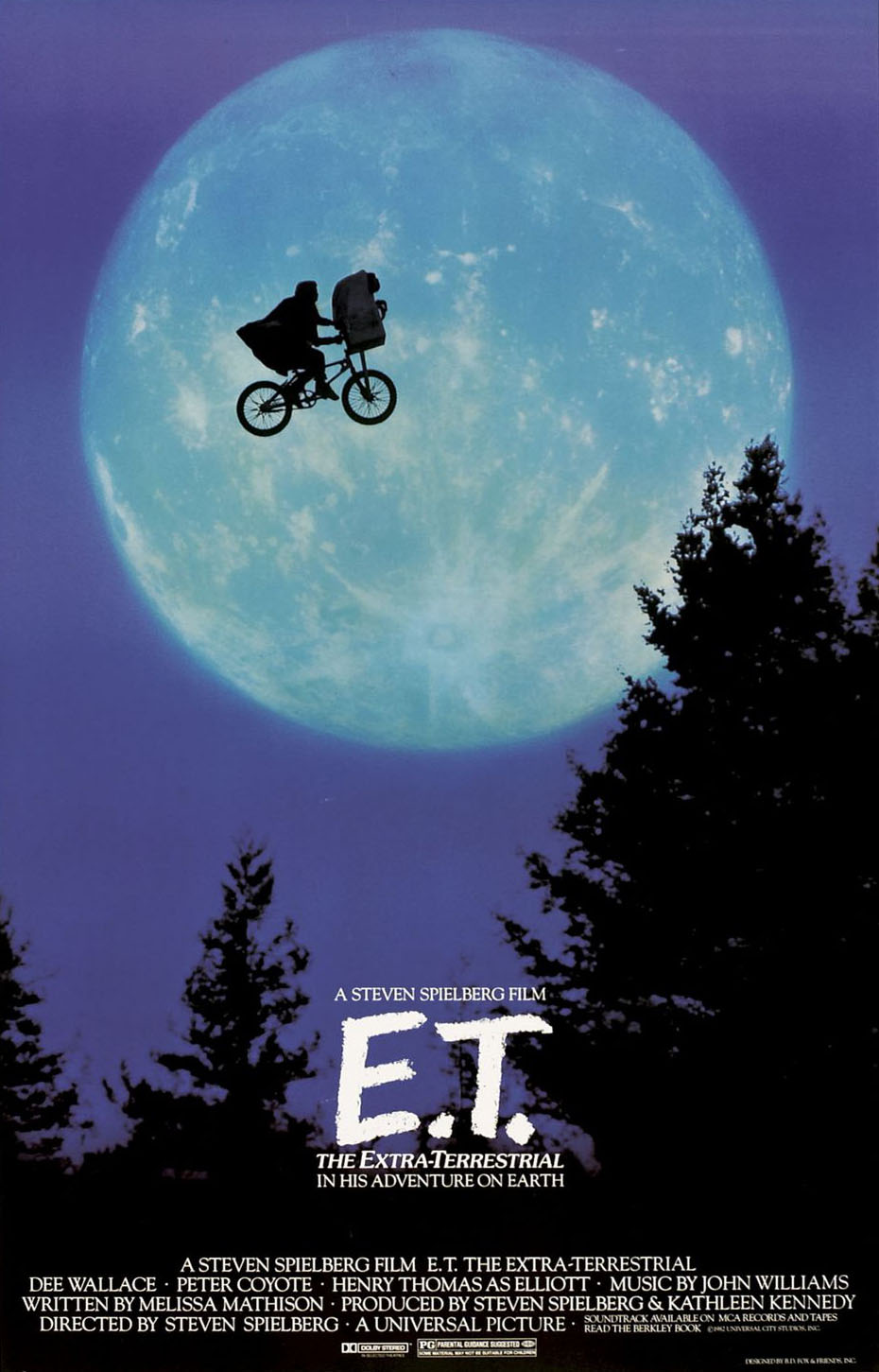

For kids (and kids at heart) with bikes: E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (1982)

(Listen, we know E.T. is not a horror movie, but finding a bicycle-forward film in this genre was impossible. E.T. takes place at and around Halloween, so it counts!)

Steven Spielberg’s beloved E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial follows Elliot (pronounced with extra vocal fry “Ell-eee-otttt”), who finds an unidentifiable creature in his family’s backyard. Lured indoors by a trail of Reese’s Pieces, the long-necked and wrinkly creature is adopted by Elliot and his siblings and dubbed E.T., short for Extra-Terrestrial. Despite the many luxuries of suburban California, E.T. needs to get back to his home planet. To summon his fellow aliens, he builds a transmitter out of objects every family had in their home in the 1980s: a Speak & Spell, a turntable, a sawblade, an umbrella. Elliot and E.T. develop a physical and psychic link, and as the film progresses, E.T.’s time on a strange planet taking its toll on both of their bodies: thus begins a race to save E.T. (and Elliot) by sending him home.

But it’s too late: despite the efforts of a medical and scientific team, E.T.’s body shuts down. (Remember how E.T. fully dies in this children’s movie? We sure didn’t!) As Elliot says his goodbyes, E.T.’s belly begins to glow and his eyes snap open: his fellow extra-terrestrials are returning for him! Elliot quickly absconds with E.T.’s now very much alive body, and an epic chase ensues. Elliot and his friends (clearly adult stunt doubles) BMX-style race through the suburban development’s construction zones, pedaling like mad and jumping bulldozed dirt piles to outmaneuver a cadre of U.S. government officials in sedans. Swaddled in a knit blanket, E.T. bounces along in Elliot’s bicycle basket as the group races for the mountains, where E.T.’s family will return for him. As a blockade of government officials raises their weapons, E.T.’s alien powers lift the bicycles into the air as the boys pedal across the sky to John William’s sweeping orchestral score.

E.T. gets a lot of things right about transportation planning: big, loud vehicles are hostile to travelers on foot (especially travelers from outer space); residential communities should be bikeable, especially for the young; and transportation connects us to our community. Although motor vehicles are an important mobility tool (a solen lab van delivers E.T. safely back to his ship, after all), bicycles offer people a freedom of affordable, active mobility at all ages. Elliot and his friends are able to help E.T. because they have reliable access to their own modes of transport. (They also have almost no adult supervision, but it was the 80s and a different time.) Without fast and reliable intergalactic travel, E.T. is marooned on an alien planet, where, despite the love and care from his new friends, his body wastes away. Returning to his spaceship literally reconnects E.T. to his fellow beings (evidenced by their glowing potbellies) and the natural world, specimens of which they have collected, cataloged, and cared for in their spacecraft.

Movie Poster: “E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial.” IMDb, June 11, 1982. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0083866/?ref_=nv_sr_srsg_0_tt_4_nm_4_in_0_q_e.t.

When we set out to watch tales of horror that featured different modes of transportation, we didn’t expect that the modalities would so actively facilitate the horror. If there’s a difference between being scared on transportation and being scared of transportation, the true horror movies on our list often fall into the latter category.

Roll Credits

While obviously these films were crafted by different artists, with different creative agendas, and from different source texts, it can still be useful to line them up next to each other and see what they have in common. As individual titles, these movies don’t condemn the whole of the transportation landscape as dangerous, but in the aggregate they share a cautionary mission. Christine, The Ritual, Horror Express, and Midnight Meat Train each casts its mode of transportation, and maybe mobility more broadly, as a type of forbidden knowledge that destroys communities under the guise of building them up.

When we set out to watch tales of horror that featured different modes of transportation, we didn’t expect that the modalities would so actively facilitate the horror. If there’s a difference between being scared on transportation and being scared of transportation, the true horror movies on our list often fall into the latter category. Perhaps this is a natural byproduct of how storytelling works. If we were writing an article on “most romantic transportation movies” for Valentine’s Day, for example, then maybe sure the modalities would have been framed as generators of human connection: cars would be presented as places for puppy love at the drive-in and subways would set the stage for innumerable meet-cutes. By this same token, E.T., geared toward children, was the sole title we watched that offered an alternate perspective on mobility as a tool of salvation and a return to community connectivity.

It’s also worth pointing out how the innate extremity of horror as a genre undermines the supposition that transportation is dangerous as much as it advances it. If we have to fear a citywide conspiracy of murders in the name of supernatural appeasement in order to fear the subway, then the actual subway isn’t that scary. By indulging exaggerated representations of longstanding transportation anxieties, these films also show us just how remote and unattached those anxieties are to the reality of our transportation.

This doesn’t mean transportation isn’t without risk; in fact, it’s an inherently risky activity, and there’s much in our transportation past and present that should scare us: the twentieth-century pattern of displacing prosperous communities of color with racist highway development; our continued dependence on the automobile in a warming world; America’s peerlessly high rate of crash-related fatality and serious injury. These concerns are largely ignored in these movies, which choose instead to emphasize superstitions we’ve stoked over decades of movement. But in their extremity, these films also remind us of which of our transportation problems are real and which aren’t, and that the effect of mobility on our communities is, and has always been, dependent upon how we use it.