July 27, 2021

In the late Middle Ages, landscape did not belong in cities. Fourteenth-century residents hurled at one another the curse “May grass grow in your streets!” evoking a city of ruin reclaimed by the wilds of nature. Well, much has changed in five hundred years. Rather than marking a city in decline, today urban landscapes tell a story of the vibrant city ahead. Grass-as well as flowering plants, shrubs, hardscape, and of course, trees-are powerful tools in the hands of landscape architects, who wield them to shape drivers’ behavior, perception, and sense of place.

Traditional transportation planning and engineering practices often view landscaping as merely the last step, the final sprucing up of a project to it look nice, or in some cases, the easiest item to remove to meet budget. But landscape architects do far more than make streets and places beautiful.

Integrating these best practices into your transportation planning efforts can increase your projects’ competitiveness and readiness for grant funding.

Landscape architecture is exceptionally thoughtful. Landscape architects design topography and integrate soil, water, and natural flora and fauna systems with the built environment using their expertise in local and regional plants. Like painters, landscape architects must consider the ways color, line, form, texture, and visual weight guide a person visually and physically through a three-dimensional, living space. Light, which changes throughout the day, as well as sound, smell, and touch inform the precise choices a landscape architect makes. Perspective and sight distance are crucial for transportation designs. The viewshed of a motorist (how far one can see) affects speed choices and perceptions of safety. Landscape architects craft patterns that unite long stretches of streets and connect destinations, and then strategically breaking those patterns to alert people to changing conditions or shifts in context.

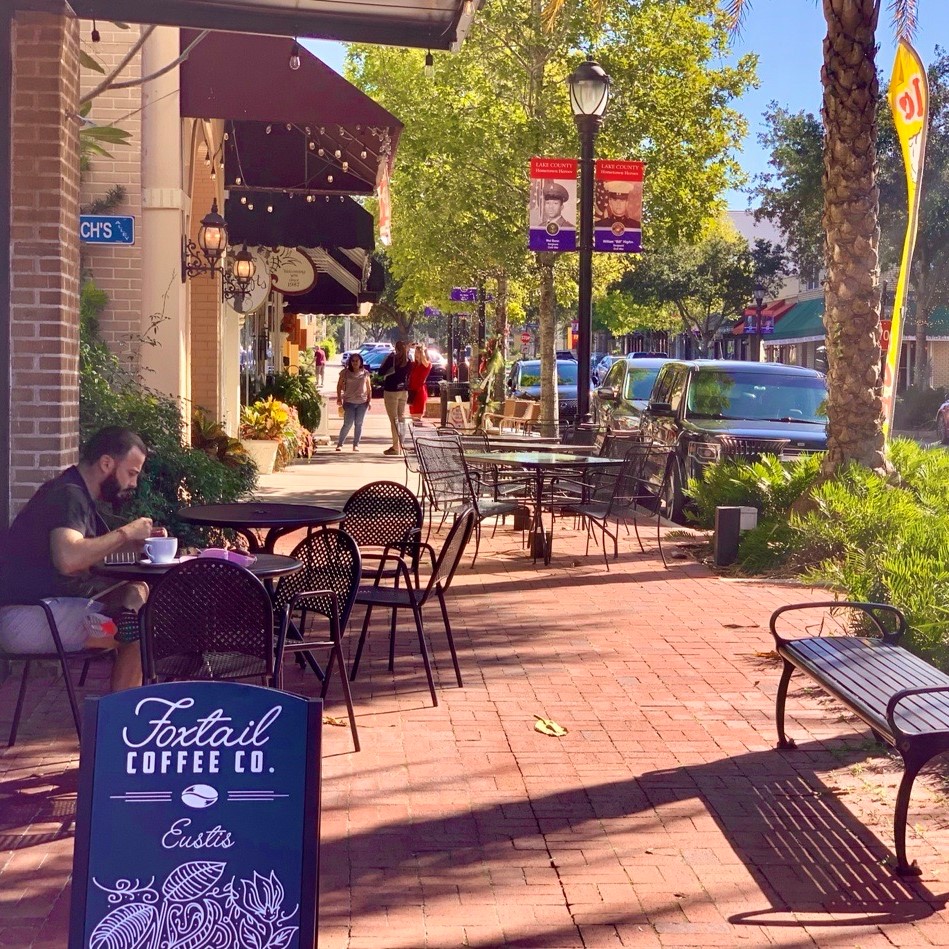

Landscape architecture gives a street or corridor its “genius loci,” or sense of place. By selecting native plants, they conjure local environments and vernacular architecture, helping people situate themselves in space and time. Medians with sandy-colored rocks and scrubby palms pull coastal features into commercial corridors. Rusticated bricks along a historic main street impress the passage of time on visitors by mirroring the worn brick storefronts. The sharing of these spaces creates “place” and builds community and belonging.

By creating spaces pleasant to walk and bike, a designed streetscape fosters active and accessible transportation. Without shade, windbreaks, or interesting features, even the best of protected bike and pedestrian facilities can feel and be hostile during certain times of the year and especially in in warm, humid climates. Designed environments also reduce driving stress and promote open, accessible movement through community spaces. Landscape architects help us rethink what streets are for by transforming transportation spaces through grading and plantings into ecosystems that simultaneously manage and filter runoff, shelter urban wildlife, prevent soil erosion, reduce pollution, and even protect fragile linear habitats from invasive species.

Magnolia Street in Eustis, Florida

Teardrop Park in New York City

However, in the landscape architect’s eye, it’s not just about the street. By reframing all public rights of way as a connected open-space system, landscape architects find creative ways to reorganize how the system serves its communities. For example, the City of Miami’s innovative Underline carved out an endangered butterfly habitat and made space for residents and their dogs in neglected space beneath an elevated railway. Atlanta’s BeltLine reserved nearly four acres along the former railway trail for an organic farm, that sells its produce, fruit, and flowers locally and with discounted prices for those paying with SNAP/EBT benefits.

Green spaces designed by landscape architects also help our brains by counterbalancing the stress, burnout, and depression associated with working indoors. Forest bathing aims to help people discover the unstructured and wonderous experience of nature: smelling plants, feeling earth, and watching wildlife. Studies consistently demonstrate that spending time in forested environments quite literally reduces blood pressure and stress hormones. And because even a view of nature benefits the human psyche, green spaces improve the mental health of people who drive through a corridor or whose offices look out onto a tree-lined street. Psychologist Rachel Kaplan found that office workers with a view of nature were in better health and reported higher job and life satisfaction than those without green views. She and her partner found that natural environments alleviate the strain of prolonged directed attention fatigue, the kind of intense focus we experience when completing work tasks, by offering a quiet moment of fascination and relaxation.

Landscape Architecture Transforms Hickory Street in Melbourne, Florida

The simultaneous safety, place-making, environmental, and psychological benefits of landscape architecture make the practice one of the most powerful tools we have as transportation teams. Consider, for example, Hickory Street in Melbourne, Florida, where native grasses now grow tall and ripple in the coastal winds. Catching movement in their peripheral vision, drivers instinctually slow down.

The wave-like grasses of Hickory Street resulted from our collaboration with the City of Melbourne and the Florida Department of Transportation (FDOT). Together, we designed a two-part complete street that stretches from the downtown historic district through in-town neighborhoods, and ultimately extending a regional hospital campus. With a subtropical climate and significant pedestrian, bike, and car traffic, this stretch of Hickory Street needed safety improvements, better water management, and a clearer sense of place. Our interdisciplinary team used landscape design, engineering, and planning experts to meet Hickory Street’s complex needs in a way that was both beautiful and functional.

The design uses bike lanes, raised intersections, and curb-less “shared space” street to provide safe, accessible mobility for multimodal users near three different parks. As the street transitions to hospital campus, the bike lanes become a multi-use path, circumventing two new roundabouts at Sheridan and Oak Streets. The design finishes with a series of rain gardens to safely return the bike lanes to the street.

With tropical, Floridian climates, stormwater management is crucial. Toward the end of the street, planted rain gardens both direct bike traffic and gather runoff. To manage another area prone to flooding, porous paving materials hold water while it slowly seeps back into the ground. By elevating driving, cycling, and pedestrian surfaces, the design avoided adding more impervious surfacing or compacted soil.

Plantings along Hickory Street mimic the coastal waters in nearby Melbourne to gently alert drivers to changes in context and the potential for other road users. At the same time, this local flora and variation of textured and color pavers visually underscores the important community features of the street.

Grasses along Hickory Street help drivers navigate the roundabout while also providing a buffer to pedestrians. The tree to the left is a live oak which will eventually grow to form a "terminating vista" to help with speed managment even before the drivers enter the roundabout.

The Role of Landscape Architects on Transportation Project Teams

The success of large projects like the Underline and the Beltline and smaller projects like Hickory Street make clear the valuable and vital skills and perspectives landscape architects bring to the table. Landscape architecture’s aesthetic features cannot be brushed aside as superficial improvements or discarded to cut costs because safety and livability improvements are difficult to quantify. Doing so limits the tools we have to improve streets and circumscribes our ability to plan sustainable, safe, and equitable streets. The FDOT Design Manual has taken leading strides in this direction by quantifying the need for “enclosure” and “street trees” as well as landscaped shorter blocks and median/curb bump-outs to help manage speed-yet there is much room for transportation landscape architecture to grow.

The time has come to again reassert the importance of landscape architects to project teams. During the Great Depression, teams of landscape architects and engineers built much of the National Parks’ mobility system. Together, they promoted tourism by constructing streets that moved with the land and building bridges and walls out of local stone. In this way, tourists moved through transportation infrastructure that felt as if it had been pulled from the land itself. However, during and the after the Second World War, collaboration fell to the wayside in the name of function, utility, and national security. By viewing landscape architects as integral team members, we can foster more nimble and creative teams, encourage innovative solutions, and better support holistic approaches to traffic safety.

We must also learn to see twenty-first-century landscape architecture not as mere beautification but as a future-oriented technological tool. Nurseries have bred more sophisticated tree species specifically to survive in harsher urban conditions, helping them to grow upwards rather than outwards. Landscape architects must consider how a space will look in the near-term but also in five, ten, fifteen, and fifty years. As they select species of trees, shrubs, and ground cover, they must contemplate growth patterns, seasonality, and how flora will change in frigid winters or blistering summers. Unlike many other mediums used in the built environment, the landscape architect’s materials are living, breathing materials and this aspect, in particular, makes them indispensable team members as we plan resilient transportation networks for communities in the face of climate change.

Finally, we must commit to reframing our research questions and design so that we can see how to best apply landscape architecture principles to planning and engineering safe, sustainable, and equitable streets. Initial research projects show positive correlations between roadside landscape improvements and crash reductions, particularly on mid-blocks, as well as indicate the cost-effective potential of greening streets for crash reduction.

Conclusion

Landscape architecture offers the transportation industry an opportunity to fine-tune our streetscapes and deftly manipulate people’s behavior and choices in a way that is as beautiful as it is utilitarian. Next time you are out, take time to appreciate the grass that very much belongs in your city. When you see the humble strip of green on a tree-lined street or that bit of shade keeping you cool on a hot summer day, know that a landscape architect was thinking about your experience many years before your visit.