September 14, 2020

How Ed Myers’ “circular reasoning” helped launch the first statewide roundabout program in the United States

“What is a modern roundabout? Where are they used? How are they different than traffic circles and what makes them function more efficiently and safely? How is the capacity of a roundabout calculated? These were the questions that I was confronted with in June of 1990.

“On that fateful day, Hurst-Rosche Engineers, Inc. was assigned the task of considering the use of modern roundabouts for a project in Prince George’s County, Maryland. What has occurred since that day has changed my life (for the better I would like to think) and has the potential to change traffic engineering in the United States for many years to come.”

Ed Myers, who is now a senior principal engineer with us here at Kittelson, penned these words in a paper published in 1993 entitled “Modern Roundabouts for Maryland.” The “fateful day” he describes refers to the day his former employer, Hurst-Rosche Engineers, was tasked with determining if roundabouts could be an applicable solution for a new interchange on the I-495 Capital Beltway. Initial concepts had run into challenges due to unforeseen environmental impacts and the costs associated with a potential collector-distributor road, and the Maryland State Highway Administration (SHA) had received a letter from U.S. Senator Barbara Mikulski suggesting that modern roundabouts deserved consideration.

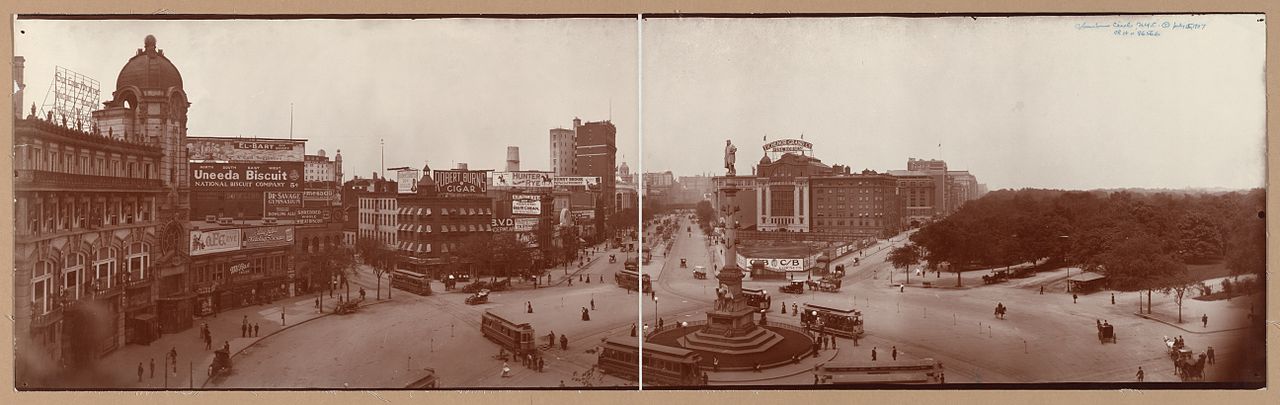

The phrase “modern roundabouts” was used to differentiate the design concept from older-style traffic circles and rotaries. Traffic circles have tied intersecting streets together since the time the first roads were built. Beginning with the use of one-way circulation at New York’s Columbus Circle in 1905, the use of various types of control at circles has been attempted for close to a century. However, by the 1950s, traffic circles in America had fallen out of favor due to the high crash rates and congestion in traffic circles – particularly at rotaries in the northeastern United States. The “modern roundabout” was developed in the 1960s when the United Kingdom adopted mandatory offside priority and proposed smaller circular intersections that forced tighter turns.

Beginning with the use of one-way circulation at New York's Columbus Circle in 1905, the use of various types of control at circles has been attempted for close to a century. However, by the 1950s, traffic circles in America had fallen out of favor due to the high crash rates and congestion in traffic circles.

To learn more about modern roundabouts and determine if they could be applicable at this location, Ed began by consulting the Highway Capacity Manual, but found no mention of roundabouts or traffic circles. So he dove into additional research published by Kenneth Todd, California Department of Transportation, and the Australian Research Board.

Mike Niederhauser, who now serves as the Maryland State Highway Administration Roundabouts Coordinator, was placed on this planning study along with Ed and a few others – “by luck of the draw,” he said. “Neither Ed nor I had any idea this would lead to a career built around roundabouts.

“We’d come into the office at 12am, 1am our time and call other countries that were seeing success with modern roundabouts: Germany, France, England, Australia. After a month we all came together with the data we had collected. One thing that stood out like a sore thumb: a total accident reduction rate of 30-50% and injury accident reduction rate of 30-90%.”

“What was perhaps the most intriguing aspect of roundabouts is that they were flourishing in so many countries,” wrote Ed in his 1993 paper. “The reasons given most often for the success and growth of roundabouts in these countries were that they reduced injury accidents, traffic delays, fuel consumption, air pollution and construction costs. At the same time, the state of New Jersey is removing traffic circles because they claim that they are high accident intersections with long delays. I then reasoned that there had to be major differences between roundabouts and traffic circles.”

“I’ll never forget the statement our then Administrator, Hal Kassoff, made when we had the data in front of us,” said Mike. “He said, ‘We wouldn’t be worth our weight if we didn’t find a location and give this a try.'”

The Difference Between Roundabouts and Traffic Circles

The planning study’s research in the summer of 1990 led them to adopt a definition of three main features that differentiated modern roundabouts from rotaries:

- Yield-at-entry: assigns the priority to circulating vehicles and forces entering vehicles to yield the right-of-way to cars in the circle

- Deflection: forcing the path of the vehicle to deflect around the central island

- Flare: the widening of the approach roadways to the roundabout

These design elements were a departure from traffic circles, where drivers were not always required to yield at entry, leading to high-speed merging.

“Some American traffic circles have one, two, or maybe even all three of the characteristics,” Ed wrote in 1993. “If the circles do incorporate these characteristics it is more likely by luck than by design. The countries that do recognize the importance of these characteristics see the exponential growth in the construction of roundabouts.”

They took this information back to the analysis of the I-495/Ritchie-Marlboro Road Interchange project, where Ed used the analysis procedure from “Evaluating the Performance of a Roundabout” by Rod Troutbeck to compare the performance of roundabouts and traffic signals at the interchange ramp terminals. His results were verified by Leif Ourston & Associates and it was decided that a diamond interchange with roundabouts at the ramp terminal intersections was an appropriate solution for the project.

The question then was: where to go from here?

“Most team members were confident that a roundabout was an appropriate solution at this interchange, but, were there other locations that the state should be considering,” wrote Ed. “Following a presentation to the Administrator on roundabouts (one of many such presentations), he suggested that we form a Roundabout Task Force. The goals of the task force were to continue research on the use of roundabouts, develop a videotape extoling the virtues of a roundabout, identify locations across the state where a roundabout may solve a particular problem, and develop guidelines for the use of roundabouts.”

The First Built Modern Roundabout in Maryland

Although the I-495/Ritchie-Marlboro Road Interchange was the catalyst for Maryland’s Roundabout Task Force, they recognized it shouldn’t be the first constructed roundabout in the state due to the amount of traffic it carried.

“We compiled a list of intersections with safety or capacity issues that were no more than a 5 out of 10 on the scale for meeting traffic signal warrants,” remembered Mike. This exercise led them to an intersection in the small town of Lisbon, Maryland.

Residents were originally quite skeptical when SHA opted to replace the crash-prone intersection at MD 144/MD 94 in Lisbon with a roundabout. There were no modern roundabouts in Maryland at the time, and only a handful in the entire US.

“I had been to a fair number of public meetings,” Ed said, “but this one was unique. 300 people came out to the public meeting. 296 were opposed, four were neutral at best. People were saying, ‘You’re experimenting with my children!’ It was an unpleasant night. So, we agreed at that meeting that we’d start with a temporary roundabout and see what they thought of it.”

SHA agreed to meet with a task force of eight citizens on a monthly basis to gauge their ongoing reaction to it. This group was assured that the roundabout would be removed at any time during the first six months if it wasn’t performing as SHA officials anticipated.

After the third month, the citizen group asked that the temporary roundabout be converted to a permanent roundabout as soon as possible. And two years later, the community asked SHA to install another roundabout to the north of the original intersection to solve similar problems.

In a press release published in 2018 celebrating the 25th anniversary of Maryland’s first constructed roundabout, the Maryland State Highway Administration wrote that there has been a 77% crash reduction and no fatal crashes since the roundabout’s inception.

The temporary roundabout in 1992. Photo from Maryland State Highway Administration.

The constructed roundabout in Lisbon, MD - the first modern roundabout in the state. Photo from Maryland State Highway Administration.

Moving Roundabouts Forward in Maryland

After MD 144/MD 94, the Roundabout Task Force met monthly for several years to identify locations where roundabouts could be appropriate. As more roundabouts got built, guidelines were needed, which SHA developed based on the Australian manuals. They also produced materials, including an eight-minute video, explaining what modern roundabouts were and how they differed from traffic circles.

“We probably had 500 of those tapes made up,” said Mike. “Every time we’d send one to a state, we’d get multiple calls requesting more. We sent the guides out to every state, which prompted calls left and right – for a year I spent a lot of my work time on the phone.”

Once Maryland had results to show for their roundabouts, Mike remembered the sudden interest of other state DOTs in learning about Maryland’s program.

“I think we were the impetus for the country,” he said. “I probably met 15-20 DOTs that would spend three or four days in Maryland. We would take them all over the state to show them urban roundabouts, eastern shore roundabouts, every different setting we had. We even had visitors from Canada who wanted to see our roundabouts. This led to doing a lot of peer review work for other states.”

Ed and Mike also spent much of their time meeting with the public in Maryland communities where roundabouts were identified to be an effective solution.

“We knew it was going to be a tough sell. Through the 90’s, I probably went to public meetings about roundabouts once or twice a month,” said Ed. “We dealt with a lot of opposition from the public at these meetings. But eventually, we noticed a change in perception as roundabouts continued to be built across the state.”

“Ed was involved in many firsts, and almost firsts, when it came to roundabouts in the US,” said Andy Duerr, who worked with Ed at Hurst-Rosche and now is a Senior Principal Engineer at Kittelson. “Maryland was the first state in the US to adopt a statewide roundabout program. Ed was also involved in one of the first urban multilane roundabouts, one of the first mini-roundabouts, and was at the forefront of designing roundabouts for pedestrians with visual impairments.”

Kittelson & Associates Meets Ed Myers

In a roundabout way, this is a Kittelson story, too.

In 1996, the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) selected Kittelson to develop the first national roundabout guide. They just had one concern: Kittelson didn’t yet have enough practical roundabout experience.

Their suggestion? Add Ed Myers to the project team.

Ed’s guidance on traffic control devices and geometric design proved to be extremely valuable on the original FHWA’s Roundabouts: An Informational Guide, a landmark document in the United States on roundabout planning, analysis and design practices. This was the beginning of Kittelson’s working relationship with Ed, as well as the expansion of our roundabout practice. The Kittelson team continued to bring Ed into projects for guidance on the geometric design side: for the first roundabout in Bend, Oregon, and a roundabout in Astoria, Oregon, which is a memorable project for Ed.

“It was my longest field visit ever,” said Ed. “I flew from Baltimore to Portland (with at least one layover). Lee Rodegerdts picked me up from there and we made the trip to Astoria. Lee and others were working on a roundabout design near the coast. This ended up being about a fifteen-hour day.”

In the late 1990s, Kittelson created a three-day roundabout short course and invited Ed as an instructor.

“I remember teaching that course with Ed,” said Lee. “In the early days, we addressed many comments from skeptical people in the class. It was not an obvious thing to the folks in the room; we had to defend the roundabout guide in every class. Attitudes toward roundabouts are very different now.”

In 1998, Ed’s relationship with the Kittelson team reached a new level: “a courtship,” described Ed. “We were in conversation for about two years over the idea of me joining the firm. I could tell it was a progressive firm, and the thing that most impressed me the most was the bright and talented young staff.”

Hiring Ed was a weighty decision on Kittelson’s part, because it meant opening an office in Baltimore. At that time, the only Kittelson offices were located in Portland, OR, Fort Lauderdale, FL, and Orlando, FL.

“The decision to hire Ed was easy. The decision to open the office was complicated,” said Lee, remembering conversations he was a part of in which firm leadership decided if they were ready to expand into the Northeast United States.

Ultimately, they decided to take the leap and on September 1, 2000, Ed joined the Kittelson team and opened our Baltimore, Maryland office.

Kittelson’s Northeast Region and Roundabout Practice Today

Kittelson’s Northeast Regional Meeting in 2019. Ed Myers is standing on the left.

Twenty years later, our Northeast Region is 10 offices and more than 60 people strong, expanding first to Reston, Virginia, then to Boston, DC, Philadelphia, Raleigh, Charlotte, Wilmington, Cincinnati, and most recently, Harrisburg.

Throughout this growth, our Baltimore office has remained a hub for Kittelson staff in the region. It’s the office where many of the leaders of our firm today, including CEO Brandon Nevers, spent their early years.

Under the leadership of Ed, Lee, and many others, our roundabout practice has grown throughout the years, too; from working with agencies across the country to design and implement roundabouts, to authoring or contributing to state-level guidance for more than nine states, to leading national research on roundabout operational, safety and design performance (NCHRP Report 572) that led to the second edition of the Roundabout Guide (NCHRP Report 672).

Looking back, we’re grateful to Ed for his expertise and guidance over the years – not just for his integral role in roundabouts, but in projects of all shapes and sizes.

“As a young engineer in the mid-2000s, I remember being surprised to learn that not only was Ed on the forefront of modern roundabouts, but he got really involved with the streetcar project in Baltimore,” said Senior Engineer/Planner Alek Pochowski. “You don’t usually find people who jump into both types of projects.

“Ed has never been a self-promoter, and I’m not sure the profession truly knows what a big role he played in bringing roundabouts to the US. But also, I don’t think Ed’s in it for the recognition.”

The Kittelson team, however, is not one to leave milestones unrecognized.

On August 30, 2020, three days before Ed’s 20-year anniversary with Kittelson, a caravan of Kittelson cars turned onto Ed’s street to celebrate in socially distanced fashion: cheering, waving, and displaying signs thanking Ed for two decades of leadership in the firm.

One of these signs summarized the significance of his work in the early days of Maryland’s roundabout program: “Because of Ed Myers, millions of people now drive in circles!”